Acute Pain Management

Steven Rosenzweig, Bernard L. Lopez, and Glenn Oettinger

Acute pain is the most common symptom for which patients seek emergency care, and analgesics account for one-third of all medications prescribed in US emergency departments (EDs). Studies consistently document that pain is often inadequately treated by physicians in the ED and other settings (1). Expediting appropriate and compassionate pain relief remains one of the greatest challenges in the practice of emergency medicine today (2).

Drugs used to treat pain act by reversing the underlying cause of pain (e.g., nitrates for angina) or by suppressing the symptom (i.e., the perception of pain). This chapter focuses on drugs used to treat the symptom of acute pain. Other medications that reverse the underlying cause of pain are discussed elsewhere in this book. Related discussions include the chapters on conscious sedation (Chapter 17), and chronic pain syndromes (Chapter 16).

PAIN ASSESSMENT

Current practice standards include pain assessment as the fifth vital sign. However, many challenges exist to the accurate assessment of pain in the ED.

Subjective Nature of Pain

Pain is an experience that has both physical and nonphysical dimensions. Physiologically, pain is mediated by a set of neurochemical events. At the level of consciousness, it is an event of personal suffering. The perception of pain and severity of suffering is highly individual. These are affected by an individual’s psychological and cultural conditioning, cognitive appraisal of pain, emotional state, and coping style.

The language of pain presents a challenge to clinical assessment. It can be very difficult for anyone to find words to convey either the quality of pain or its severity. Descriptions lack the preferred exactness of medical terminology. People resort to imagination and simile: “My back feels as if it is caught in a vise,” or “My hand feels like it is on fire.” Another problem is that patients and physicians use words differently. For example, a patient may use the word sharp to mean severe, whereas the physician may assume it to mean knifelike. Perhaps the most classic example is the patient with acute coronary syndrome who denies chest pain but will admit to chest pressure upon further questioning. Active listening and clarification yield critical information about pain severity and provide clues to etiology.

One of the most important aspects of the pain experience is the meaning it holds for the sufferer. Pain is often greater when its cause is perceived to be life threatening or when it is associated with emotional trauma. Conversely, pain that is perceived to offer some secondary gain can be easier to bear.

Objective Signs of Pain Are Unreliable

The emergency physician cannot rely on objective findings in estimating pain severity: The patient need not appear in pain to actually be in pain. There are no objective signs that can be used to accurately gauge the magnitude of a patient’s pain. Indicators such as heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory pattern, facial expression, and body posture are not reliable. The presentation of pain may be obscured by the effects of medication such as β-blockers that blunt the adrenergic response to pain. Other medications may produce sedation but not analgesia: Drowsiness does not mean absence of pain. Pain may be underdiagnosed because of a patient’s cultural bias toward stoicism or complex coping mechanisms, such as joking or maintaining a facade of being calm.

Equally unreliable is an estimate of pain severity based on its etiology. Can a toothache be more painful than salpingitis? Should an ankle sprain hurt less than pleurisy? These questions cannot be answered, because suffering depends on each individual’s pain threshold and sensitivity to a particular condition.

Utilizing the Patient’s Self-Report

The subjective nature of pain means that the single most reliable method of assessing pain severity is the patient’s self-report. Clinical judgment must always be guided by the patient’s own assessment. This situation in which the patient knows more than the doctor is a role reversal with which many physicians feel uncomfortable. Nevertheless, accurate pain assessment must acknowledge the authority of the patient or the insight of a close family member or friend.

Asking the patient whether or not the pain is “tolerable” or “bearable” provides a straightforward assessment of treatment urgency. Patients can be assisted in conveying pain severity with a visual analog scale (VAS) or numeric rating scale (NRS); these have been validated for use in the ED (3,4) and either can be used. The VAS has been typically used for research purposes and requires the patient to physically mark a 100-cm line and the examiner to measure the mark with a ruler. The NRS is administered verbally with the examiner giving clues to the anchor points of 0 and 10. These scales need to be explained (e.g., 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst pain imaginable). Extreme ratings (e.g., 10 out of 10) should prompt clarification; these may indicate life-threatening pathology such as a subarachnoid hemorrhage or ischemic bowel, or alternatively reveal the severity of a patient’s fear and anxiety. Asking a patient to relate their current pain to a past painful condition (e.g., pain of childbirth) can further assist the interpretation of pain scores.

Assessing pain in patients who are nonverbal or who have limited verbal ability is especially challenging. Numerous pain assessment scales are available that rely on behavioral indicators (e.g., grimacing and restlessness).

Distinguishing Pain-Avoiding Versus Drug-Seeking Behavior

The greatest impediment to accepting a patient’s self-report of pain is the physician’s concern of being manipulated into giving opioids to someone who is feigning illness. Bear in mind that pain is the most common reason for drug-seeking behavior. Even a legitimate patient may feel the need to dramatize distress to convince the doctor of his or her need. It may indeed be impossible to know for certain whether the patient’s complaint is a sham; the gain of thwarting the possible abuser must always be weighed against the risk of withholding relief from the person who is truly suffering.

Opioid tolerance must not be misunderstood as drug-seeking behavior. Patients with chronic pain syndromes who are maintained on opioid therapy would require supplemental opioid dosing for superimposed acute pain syndromes. Methadone maintenance and combination of buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone) treatments for addiction do not provide analgesia and these patients would also require supplemental opioid if indicated. Patients treated with sustained-release naltrexone (Vivitrol) for alcohol or opioid dependence are a special case and require cardiopulmonary monitoring with dedicated personnel during reversal of opioid blockade for analgesia.

The diagnosis of drug abuse is based on a pattern of behavior that is often difficult to be established during a single ED encounter. Nevertheless, a few important steps can be taken: Perform a detailed history and physical examination, being alert to inconsistencies and signs of substance abuse (1); review prior ED and hospital medical records (2); obtain patient permission to confirm the medical history by contacting the personal physician or reviewing outside medical records (3); and develop an ED policy for evaluation and management of patients who raise concerns (4). This may include use of HIPAA compliant habitual patient files, criteria for urine drug testing, and developing a multidisciplinary case management system for selected patients.

Assessing Pain in Vulnerable Populations

As in any adult, pain in a child should be anticipated and aggressively treated. However, children are much less likely than adults to be given adequate analgesia for the same painful condition (5). This observation has been attributed not only to the difficulties inherent to pain assessment but to the persistent myth that young children do not experience or remember pain. Older children are generally able to describe their pain or point to pictures on a pain analogue scale. When assessing pain in younger children and infants, the quality of cry, facial expression, changes in vital signs, and impressions of the caretaker should all be taken into account.

Historically, pain has often been undertreated in older adults. Effective history-taking often requires greater time and patience. Verbal assessment may be limited due to dementia or delirium (6). Unconscious ageist bias may cause the EP to minimize or dismiss the patient’s complaints.

Pain assessment depends upon communication and empathy. Medical care across lines of social difference between EP and patient poses challenges to both. Language discordance between physician and patient is an obvious impeding factor. Discordance in race, ethnicity, culture, class, gender, age, and physical ability is also significant. Studies have shown the undertreatment of pain in minoritized populations (1). Physicians must be willing to reflect on negative stereotyping and implicit biases that may interfere with accurate pain assessment, and be particularly self-aware when treating these patients.

ED MANAGEMENT

Expediting Relief

Pain relief should be timely. Unnecessary delays can often be averted. Patients often can and should be treated before a definitive diagnosis is established. Initial interventions can be nonpharmacologic (discussion follows). When the diagnosis depends solely on a laboratory or radiographic finding, there is no need for delaying analgesia while a time-consuming evaluation is proceeding.

The belief that analgesics, particularly opioids, will obscure the underlying diagnosis is generally unfounded. Although it is common to withhold such medication from a patient with abdominal pain who may need surgical evaluation, this practice is not supported by clinical studies (7,8). On the contrary, the judicious use of short-acting agents will serve the needs of both the patient and the consulting surgeon. Providing pain relief may actually enhance the patient’s cooperation and improve the accuracy of the examination. Factors to consider in the administration of analgesics include severity of abdominal pain and speed of the surgical consultation (9). The emergency physician should consider administering analgesics with the target of reducing patient suffering but not obliterating the pain to allow a useful physical examination by the surgeon. Ironically, analgesics often continue to be withheld in the ED even after a decision has been made to take a patient to surgery. As the patient’s most important advocate, the emergency physician must coordinate a rational and humane approach that takes into account the distress of the patient and the availability of the consultant.

Pain should be treated even if informed consent may subsequently be required. The practice of withholding all opioids from a patient who might later need to sign a consent form for surgery or other procedure is unjustified. Informed consent requires decisional capacity and voluntariness. Concern that any dose of opioids compromises decisional capacity is unfounded. Pain itself is distracting and mind altering; its relief can enhance rational decision making. Analgesia can be titrated without clouding consciousness; in rare cases, an opioid antagonist could be administered. The message that pain medication will be administered only after the consent form is signed is itself coercive and violates the requirement of voluntariness.

The physician should anticipate and treat pain before it develops. Good pain management involves anticipating pain prior to its onset or recurrence. Medications should be given before painful procedures (see Chapter 17). Similarly, patients should be discharged with appropriate medication for pain that may continue or recur.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

A variety of simple and effective interventions can reduce pain.

Provide physical comfort measures. Attending to the overall physical comfort of the patient can alleviate factors that aggravate pain. This includes such actions as helping the patient find a more comfortable position, adjusting the lighting in the room, warming a patient who feels chilled, immobilizing injured extremities, and applying ice and elevation to closed bone and soft tissue injuries.

Provide psychological support. Physical suffering is amplified by fear, anxiety, and helplessness. Fear often relates to the thought that the cause of pain is life threatening or permanently disabling. New pain in a cancer patient raises the specter of disease progression. Patients with chest pain often present with a fear of myocardial infarction. A laborer may associate an acute shoulder injury with the alarming possibility of permanent loss of income. Information and appropriate reassurance may reduce the amount of analgesics needed. Supportive family members or friends should be allowed to sit with the patient. For unaccompanied patients, facilitating phone contact with a friend or family member may provide significant comfort.

It is also important to address the patient’s expectations regarding pain medications. The emergency physician should let the patient know from the outset how much time it will take for the medication to work and whether to anticipate partial or complete relief. In addition, the physician can assure the patient that more analgesics can be administered as needed. This can allay a premature concern that the drug “is not working.”

Distress also arises in response to the ED experience itself. Patients find themselves in a harsh and unfamiliar milieu, feeling vulnerable, dependent on strangers, and relatively helpless. Building rapport, dignifying interactions, and restoring some sense of control to patients are all essential in emergency pain management.

Pain and distress may also be helped by simple hypnosis or guided imagery techniques that relax the body and calm the mind. Videos, storytelling, and imagining favorite places or activities are distraction techniques used for pediatric patients. The role of complementary and alternative therapies for adjunctive, acute pain management in the ED is not known. Although the overall analgesic efficacy of acupuncture has been established, limited research has been conducted on its application in the ED.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Dozens of drugs are available to treat pain. To select the best regimen for an individual patient, the emergency physician should consider the following:

1. How intense is the pain?

2. How quickly is pain relief required?

3. Can the patient take oral medications?

4. Are there contraindications to particular agents?

The answers to these questions help direct the choice of drug, dose, and route of administration.

Aspirin and Acetaminophen

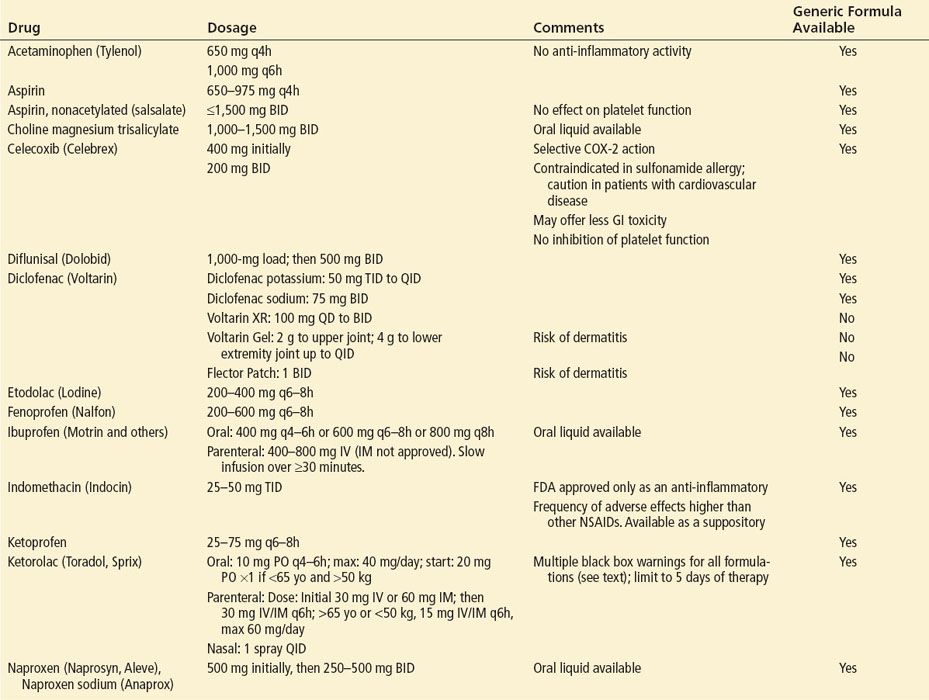

Aspirin and acetaminophen are equally effective for the relief of mild-to-moderate pain. eTable 15.1 lists dosing recommendations for these drugs. Aspirin, the prototype nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), is believed to work by blocking cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, thereby inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins, which mediate both pain and inflammation. Unlike aspirin, acetaminophen lacks anti-inflammatory properties, and its central mechanism of action is poorly understood.

eTABLE 15.1

Dosing Information for Nonopioids

Aspirin commonly leads to gastrointestinal (GI) distress. It very rarely causes a hypersensitivity reaction (more common among asthmatics with nasal polyps), characterized by bronchospasm, urticaria, rhinitis, and even shock. Aspirin inhibits platelet function, although salsalate, a nonacetylated aspirin product, does not have this effect. Because acetaminophen is free of these side effects and hypersensitivity risk, it is often the preferable drug. It is available as a rectal suppository for patients who cannot tolerate oral administration.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

At usual doses, NSAIDs are not as safe as acetaminophen but are generally better tolerated than aspirin. All six major chemical classes of NSAIDs inhibit COX but also act through nonprostaglandin-mediated pathways. Doses in the higher range are generally required to achieve anti-inflammatory effects, which may not be seen for a few days. Although no oral NSAID has emerged as a consistently superior analgesic, it is widely believed that an individual patient may respond to one agent (or chemical class) and not another.

Nonselective Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Older, nonselective NSAIDs inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes and may directly modulate neutrophil responses (see Chapter 304). When given as a single, full dose in the acute setting, most NSAIDs are more effective than aspirin or acetaminophen. In some situations, they provide analgesia equal or superior to certain oral opioids.

The onset of analgesia is within 1 hour for the majority of NSAIDs. For drugs with a relatively long half-life, such as diflunisal and naproxen, onset of analgesia is considerably longer but can be hastened by administration of a loading dose. For patients who cannot swallow pills, several agents are available in a liquid form eTable 15.1. For patients who are vomiting or for whom oral medications are contraindicated, rectal suppositories of naproxen and indomethacin are available; another option is parenteral ketorolac, discussed below.

Parenteral NSAIDs

Ketorolac was the first NSAID available in the United States for parenteral administration in the ED, either IM or IV. There is controversy as to whether the analgesic efficacy of parenteral ketorolac is generally comparable to that of parenteral opioids. For example, a single dose of IV ketorolac may be at least as effective as titrated, IV opioid in relieving pain in patients with renal colic (10). However, it is important to note that its efficacy in renal colic appears to be related to ureteral or renal prostaglandin mechanisms and may not be generalizable to other painful conditions. When studied in the ED setting, parenteral ketorolac does not provide superior analgesia to oral ibuprofen (11,12). Given parenterally, ketorolac does not act any faster than many oral NSAIDs: Drug effect is limited by the time to prostaglandin inhibition, not absorption. Thus, in many instances parenteral ketorolac offers no advantage over far less expensive alternatives. Ketorolac also exists in oral and intranasal formulations.

Ketorolac is associated with the greatest adverse event potential among all NSAIDs and carries black box warnings for GI risk, cardiovascular risk, renal risk, bleeding risk, fetal risk, and risk to nursing infants. Risk increases with duration of use that should be limited to 5 days maximum for all forms of ketorolac. Dosages must be reduced in pediatric and geriatric populations.

Intravenous ibuprofen (Caldolor) carries fewer black box warnings and may be a safer alternative. It is not approved for IM administration.

Topical Diclofenac

Pharmacokinetic data suggest that topically applied NSAIDs can result in enhanced local concentrations without significant toxic systemic effects. Nevertheless, topical Diclofenac still carries black box warnings for cardiovascular and GI risks. Voltaren Gel and Flector Patch are approved for treatment of minor sprains, strains, and contusions. Patches are considered to provide more consistent dosing than gel. Both of these nongeneric preparations are expensive but do provide adequate pain relief and can be prescribed from the ED.

Selective COX-2 Inhibitors (COXIBs)

COXIBs selectively block COX-2, the form of COX that mediates inflammation, without affecting COX-1, the inhibition of which can produce gastric injury (13). They are no more effective than nonselective, less costly NSAIDs. Celecoxib (Celebrex) is currently the only COXIB available for prescription in the United States, with others withdrawn from the market owing to higher risk of cardiovascular thrombotic events. Celecoxib may have an improved gastric safety profile compared with nonselective NSAIDs but still carries a black box warning for GI risk. COXIBs do not interfere with platelet function. They may be considered for a highly select group of patients at risk for peptic ulcers who have a well-established indication for NSAID treatment, or perhaps for patients at increased risk of bleeding.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs do not cause respiratory depression and rarely cause mental clouding. Given their anti-inflammatory properties, they treat the cause and the symptom of pain in conditions such as inflammatory arthritis or soft tissue injury. NSAIDs do not have abuse potential. NSAIDs carry black box warnings for cardiovascular and GI risks. Ketorolac carries additional black box warnings as mentioned above. The risk of cardiovascular thrombotic events increases with the presence of concomitant risk factors and duration of use. While other COXIBs may have posed the greatest cardiovascular risk, celecoxib may be associated with a lesser risk than nonselective NSAIDs (14).

Dyspepsia, the most common side effect, can be minimized by administering the drug with food or an antacid. Less commonly, NSAIDs lead to ulcers and upper GI bleeding and perforation, complications that are seen more with chronic rather than short-term use but may occur any time during treatment and without warning, especially in the elderly. NSAIDs are thus strongly contraindicated in patients with active ulcer disease and should be given with great caution to those with a history of upper GI bleeding. The incidence of GI bleeding may be dose dependent; daily doses of ibuprofen exceeding 1,500 mg are associated with increased risk. Other risk factors for GI complications include patient age older than 60 years and concurrent steroid or anticoagulant use (15). In such high-risk patients, the chance of GI bleeding can be reduced by coadministration of a proton pump inhibitor or misoprostol, at least with long-term NSAID use. The benefit these agents offer with short courses of NSAID is less well established. Other agents that were often used for prophylaxis of NSAID-related GI complications are either ineffective (antacids, sucralfate) or marginally effective (H2 blockers). COXIBs, without gastroprotective drugs, may represent another therapeutic option in patients with risk factors for GI bleeding.

All NSAIDs, including COXIBs, may affect the kidneys, causing fluid retention and renal insufficiency, and possibly acute renal failure. Patients at greater risk for renal complications include those with chronic renal insufficiency, those with reduced renal perfusion (congestive heart failure or cirrhosis), and those taking diuretics or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. NSAIDs should generally be prescribed for no more than a few days in this patient population.

Because they interfere with platelet function, nonselective NSAIDs predispose to bleeding and should not be given to patients with thrombocytopenia or intrinsic clotting abnormalities. They should generally not be used in patients receiving anticoagulants and in those suspected of internal bleeding, as in the case of severe headache with possible subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Very rarely, NSAIDs cause hypersensitivity reactions such as urticaria and bronchospasm; patients who are sensitive to aspirin are at greater risk. NSAIDs are generally contraindicated during pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester, because of known effects on the fetal cardiovascular system (closure of the ductus arteriosus).

Opioid Analgesics

Opioids are usually the first-choice drugs for the prompt relief of severe, acute pain. Unlike the NSAIDs, they have no ceiling on analgesic effect. Given IV, they work within minutes, and their effect can be titrated and reversed. Many patients treated with these agents, however, do not receive adequate pain relief because of physicians’ misconceptions about correct dosing, route of administration, and adverse effects.

Dosing by Titration

The effective analgesic dose varies considerably among patients; the correct dose of opioid is the dose that works. While some adult patients may respond to a low dose (i.e., morphine 2 mg IV), others may require higher doses for adequate pain relief. The “given” initial doses published in various references can serve only as general guidelines (16). Therefore, in the initial treatment of severe pain, it makes sense to titrate small frequent doses to effect. In pediatrics, weight-based dosing (i.e., morphine 0.1 mg/kg/dose IV) is traditionally used to guide safe and effective initial treatment (Table 15.1 and eTable 15.2).

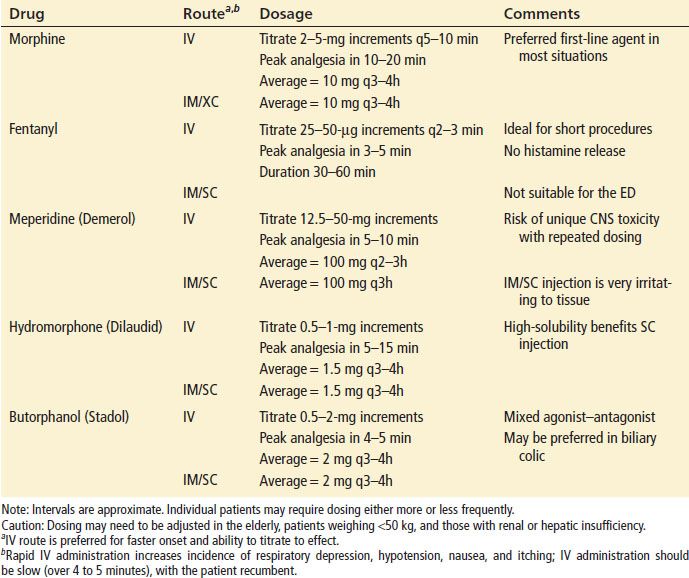

TABLE 15.1

Dosing Guidelines for Parenteral Opioids