INTRODUCTION

Pain is the most common presenting symptom for patients coming to the ED, with 75% to 80% of all patients having pain as their primary complaint.1 Despite increasing research and information about pain management, oligoanalgesia, or the under treatment of pain, persists.2,3,4,5 While all patients are susceptible to oligoanalgesia, certain subgroups, such as ethnic minorities, the aged, the very young, and those with diminished cognitive function, are more at risk (Table 35-1).6,7,8,9 Pain management is further influenced by concerns of prescription opioid misuse, a rising concern in all age groups but most notably in adolescents and young adults. Pain and addiction are not mutually exclusive,10 and appropriate treatment of acute pain should not be withheld for fear of facilitating drug misuse.

| Patient Related | Provider Related | System Related |

|---|---|---|

Ethnicity, gender, age (very young, very old) Diminished cognitive function Fear of medications: addiction, side effects Acceptance of pain as being inevitable Unwillingness to bother healthcare providers | Inadequate education No objective measuring tool for pain Accepting only pain reports that conform to our expectations Perception of addiction and drug-seeking behavior | Lack of clearly articulated standards Paucity of treatment guidelines Fear of regulatory sanctions Lack of healthcare provider accountability |

Specific measures to treat pain should occur in addition to, and at the same time as, treatment of the underlying illness or injury. It is not possible to generalize the extent and quality of pain control needed for a specific patient. For example, pain is an indicator of ongoing cardiac ischemia, and the goal should be to eliminate all pain. On the other hand, a patient with a traumatic injury may choose to endure more pain out of personal or cultural beliefs. Physicians may limit analgesics in those with head injuries to perform serial neurologic examinations. Whenever possible, medications that act on specific sites that initiate the pain signal—a mechanistic approach—are preferred to agents such as opioids that mask pain, which is a symptomatic approach. Current migraine treatment is an excellent example of the mechanistic approach; preferred treatment includes a serotonin agonist (triptan)11 or a dopamine antagonist (phenothiazine),12 rather than opiates.13,14

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Pain is the physiologic response to a noxious stimulus, whereas suffering—the expression of pain—is modified by the complex interaction of cognitive, behavioral, and sociocultural dimensions. Individual pain experience is therefore not static, but varies depending on current and past medical history, physical and emotional maturity, cognitive state, meaning of pain, family attitudes, culture, and environment. Emotions can modify pain either negatively or positively: fear and anxiety may accentuate pain, or pain can be suppressed completely if an essential task must be performed or if there is acute concern about a loved one.

The peripheral nervous system (e.g., nociceptors, C fibers, A-δ fibers, and free nerve endings) initiates the sensation of somatic pain by responding to a noxious stimulus and sending a neuronal discharge to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.15 Neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord integrate and modulate input from multiple peripheral nerves and other sensory stimuli. Transmission then proceeds up the spinal cord to the CNS (e.g., hypothalamus, thalamic nuclei, limbic system, and reticular activating system) where further integration and processing generate the perception of pain. Identification and localization of pain, cognitive interpretation, and triggering of emotional and physiologic reactions also occur at these central sites. Unlike somatic pain, which is easily localized, visceral pain pathways are more complex and differ in structure from somatic pain pathways, which may explain the poor localization of visceral pain.

Opioid analgesics work by binding to receptors in the spinal cord and brain. There are four types of opioid receptors: three classic families (delta, kappa, and mu, each with identified subtypes) and nociceptin, a receptor with significant structural homology. These receptors are found in the brain, spinal cord, and GI tract where their physiologic function is to interact with endogenous dynorphins, enkephalins, endomorphins, endorphins, and nociceptin. Opioid analgesics interact with these receptors in varying degrees, accounting for the difference in desired and adverse effects among the drugs in this class. Stimulation of the mu-1 (μ1) receptor produces supraspinal analgesia. Stimulation of the mu-2 (μ2) receptor results in euphoria, miosis, respiratory depression, and depressed GI motility. Stimulation of the delta (δ) receptor produces analgesia, but less than the μ1 receptor, and also exerts an antidepressant effect. Stimulation of the kappa (κ) receptor produces dysphoria, along with dissociation, delirium, and diuresis by inhibiting antidiuretic hormone release.

EVALUATION

Document the degree of pain on initial assessment. This process serves to identify patients with severe pain, facilitates treatment, and meets the mandates of regulatory agencies that promote assessing and treating pain. ED pain assessment should determine duration, location, quality, severity, and exacerbating and relieving factors. The patient’s subjective reporting of pain, not the physician’s impression, is the basis for pain assessment and treatment. There is at best a weak correlation between nonverbal signs, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, and changes in patient expression and movements, and the patient’s report of pain, so do not rely on these to determine the severity of a patient’s pain16,17 or response to treatment.18 Because pain is dynamic and changes with time, periodic pain reassessment is needed.

Although standardized scales for measuring reported pain are commonly used, their impact on effective pain control is uncertain.19,20 The primary value of pain scales is their essential role in research enabling reproducible comparisons of interventions. Some studies have suggested that the use of pain scales may actually decrease the provision of analgesics. Given the subjectivity both of pain reporting and the provider’s interpretation of such reporting, the use of simple descriptors such as “a little” or “an awful lot” is equally valid in the clinical setting. What is important is that the patient’s subjective reporting should be the basis for assessment and management. For most, but not all, painful conditions, the goal is to control pain to the level the patient desires. Asking if the patient requires more analgesic may even be simpler and accomplish more than using any standardized pain evaluation tool.21,22

The purpose of pain scales is to quantitate pain severity, guide the selection and administration of an analgesic agent, and reassess the pain response to determine the need for repeated doses or more effective analgesics. Several self-report instruments are valid in patients with acute pain, and some require only a verbal response (Table 35-2). Each tool has advantages and specific limitations. ED personnel in any one location should use the same tool so information collected is standardized. A value assigned by a patient is not an absolute value but rather a reference point based on past personal experience.23

| Scale | Method | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Adjective rating scale (Figure 35-1) | Patient rates pain by choosing from an ordered list of pain descriptors, ranging from no pain to worst possible pain, with allowance for marks between discrete labels. | Easy to administer. |

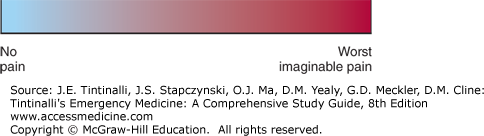

| Visual analog scale (VAS) (Figure 35-2) | Patient places a mark that best describes pain intensity along a 10-cm linear scale marked at one end with a term such as no pain and at the other end with worst imaginable pain. | Pain intensity measured in millimeters from the no-pain end. A difference of 13 mm is the minimum clinically significant change noticeable by patients, whereas an average decrease of 30 mm appears to be the minimum acceptable change for pain control.* |

| Numeric rating scale (Figure 35-3) | The patient is asked to self-report pain on a scale of 0 to 10 with descriptors. | Can be used in patients with visual, speech, or manual dexterity difficulties by using upheld fingers. Not as discriminating as the VAS. |

| 5-Point global scale | Patient rates pain as: 0 = none 1 = a little 2 = some 3 = a lot 4 = worst possible | A decrease of 1 point is a large change; scales with more choices allow monitoring of small changes in pain and may be more sensitive to changes. |

| Verbal quantitative scale | The patient is asked to self-report pain on a scale of 0 to 10 without descriptors. | Most commonly used scale; easy to administer. |

The elderly often report pain differently from younger patients because of physiologic, psychological, and cultural changes associated with aging. Visual, hearing, motor, and cognitive impairments can be barriers to effective pain assessment. Using a numerical pain scale, the elderly may also experience a decrease in the minimum clinically significant noticeable difference in acute pain over time.24,25 Family members and caregivers are often able to judge nonverbal actions of the patient as representing pain or distress, so they should be used if available to help with pain assessment in the noncommunicating elderly patient.

Trauma patients and those with acute intoxication do not perform as well on pain scales.26 Women are more likely to express pain and to actively seek treatment for pain,27,28 yet there is a tendency to underestimate and undertreat pain in women. Ethnicity of both the patient and the physician has a bearing on different cultural concepts of pain and on the characteristics of culturally appropriate pain-related behaviors.7 Translators and family members should be asked to provide assistance. There is also interplay between the ethnicity of the patient and that of the physician.7 When there are language difficulties or cross-cultural differences, the visual analog scale is the preferred pain assessment tool because it is the least affected by these factors.

PHARMACOLOGIC PAIN TREATMENT

The administration of pharmacologic agents is the mainstay of acute pain management. The key to effective pharmacologic pain management in the ED is selection of an agent appropriate for the intensity of pain and it’s time to onset of analgesic activity, ease of administration, safety, and efficacy.29 Acute pain is usually accompanied by anxiety and feelings of loss of control. If verbal reassurance combined with an analgesic does not suffice, an anxiolytic may be useful.

The “tiered approach” to pain management starts with an agent of low potency regardless of pain intensity, assesses the response after a clinically relevant period, and sequentially changes to agents of higher potency if pain persists. The tiered approach for acute pain management unnecessarily subjects the patient to more prolonged suffering. It is preferable to select initial analgesics that are appropriate to treat the intensity (mild, moderate, or severe) of the patient’s pain. Agents such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be considered for mild to moderate pain, and systemic opioids for moderate to severe pain (Table 35-3). In specific instances such as renal and biliary colic, a parenteral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug may control severe pain, although combination therapy with an opioid is usually superior.

When possible, local anesthesia is a useful adjunct (Table 35-4). Peripheral nerve blockade for pain control and for procedures is a useful option, especially if guided by US (see chapter 36, Local and Regional Anesthesia).30,31

| Class | Route | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | PO | Mild/moderate somatic pain plus severe colicky pain | Use caution in the elderly and in those with renal, GI, and hematologic disorders |

| Parenteral | Does not require GI absorption | No more effective than PO More costly | |

| Opioids | PO | Can be effective if adequately dosed | Variable absorption, somewhat slower onset |

| IM | No IV access required | Painful injections Unreliable absorption | |

| IV | Ideal for titrated dosing | Need for IV access | |

| Local anesthetics | Infiltration | Technical ease | Limited duration of action |

| Peripheral nerve block | Opioid sparing | Technically difficult at some sites Facilitated with use of US guidance |

Opioid analgesics are the cornerstone of pharmacologic management of moderate to severe acute pain (Table 35-5). The term opiate refers to agents that are structurally related to natural alkaloids found in opium, the dried resin of the opium poppy. The term opioid describes any compound with pharmacologic activity similar to an opiate, regardless of chemical structure. Opioid use in the ED is often affected by concern for the precipitation of adverse events, such as respiratory depression or hypotension, or for facilitating drug-seeking behavior. As noted, a greater concern is oligoanalgesia and inadequate dosing of opioids when used. Considerations for use of opioids include (1) desired onset of action, (2) available routes of administration, (3) achievable frequency of administration, (4) concurrent use of nonopioid analgesics and adjunctive agents, (5) possible incidence and severity of side effects, and (6) continuation of the agent in an inpatient or ambulatory setting

| Drug [Class] | Typical Initial Adult Dose | Pharmacokinetics | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphine [natural alkaloid] | 0.1 milligram/kg IV | Onset: 1–2 min (IV) and 10–15 min (IM/SC) | Histamine release may produce transient hypotension or nausea and emesis; neither require routine adjunctive treatment. |

| 10 milligrams IM/SC | Peak effect: 3–5 min (IV) and 15–30 min (IM) | ||

| 0.3 milligram/kg PO | Duration: 1–2 h (IV) and 3–4 h (IM/SC) | ||

| Hydromorphone [semi-synthetic alkaloid] | 0.015 milligram/kg IV | Onset: 3–5 min (IV) | More euphoria inducing than morphine. |

| 1–2 milligrams IM | Peak effect: 7–10 min (IV) | ||

| Duration: 2–4 h (IV) | |||

| Fentanyl [synthetic piperidine] | 1.0 microgram/kg IV | Onset: <1 min (IV) | Less cardiovascular depression than morphine. High doses can cause chest wall rigidity (>5 micrograms/kg IV). |

| Peak effect: 2–5 min (IV) | |||

| Duration: 30–60 min (IV) | |||

| 100-microgram nasal spray in 1 nostril | Used for breakthrough pain in opioid-tolerant cancer patients. Wait >2 h before treating another episode. May increase dose by 100 micrograms per episode. | ||

| 100-microgram buccal mucosa tablet | Used for breakthrough pain in opioid-tolerant cancer patients. May repeat after 30 min. Wait >4 h before treating another episode. May increase dose by 100 micrograms per episode. Available transmucosal forms not bioequivalent. | ||

| Meperidine (pethidine) [synthetic piperidine] | 1.0–1.5 milligrams/kg IV/IM | Onset: 5 min (IV) | Contraindicated when patient is taking a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Neurotoxicity may occur when multiple doses are given in the presence of renal failure. |

| Peak effect: 5–10 min (IV) | |||

| Duration: 2–3 h (IV) | |||

| Oxycodone [semi-synthetic alkaloid] | 5–10 milligrams PO OR 0.125 milligram/kg PO | Onset: 10–15 min (PO) | Lower incidence of nausea. Possible inadvertent acetaminophen overdose with combination agents. |

| 30 milligrams PR | Duration: 3–6 h (PO) | ||

| Hydrocodone [semi-synthetic alkaloid] | 5–10 milligrams PO | Onset: 30–60 min (PO) | Lower incidence of nausea. Possible inadvertent acetaminophen overdose with combination agents. |

| Duration: 4–6 h (PO) | |||

| Codeine [natural alkaloid] | 30–60 milligrams PO | Onset: 30–60 min (PO) | High incidence of GI side effects. Some patients cannot convert to codeine-6-glucuronide and morphine. Possible inadvertent acetaminophen overdose with combination agents. |

| 30–100 milligrams IM | Duration: 4–6 h (PO) | ||

| Tramadol [other] | 50–100 milligrams PO | Onset: 10–15 min (PO) | CNS side effects common. |

| Duration: 4–6 h (PO) |

Opioids need to be titrated to effect; patients differ greatly in their response to opioid analgesics.32,33,34 Variation in pain reduction is related to age, initial pain severity, and previous or chronic exposure to opioids, but not body mass35,36 or gender.37 Relative potency estimates provide a rational basis for selecting the appropriate starting dose to initiate analgesic therapy,38 changing the route of administration (e.g., from parenteral to PO), or switching to another opioid (Table 35-6), but undue reliance on these ratios is an oversimplification with potential for over- or underdosing.39

| Drug | Equipotent IV Dose (milligrams) | Equipotent PO Dose (milligrams) | Equipotent IM Dose (milligrams) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 10 | 60 (acute) and 30 (chronic) | 10 |

| Hydromorphone | 1.5 | 7.5 | 1.5 |

| Fentanyl | 0.1 | 0.2 (transmucosal) | 0.1 |

| Meperidine (pethidine) | 75 | 300 | 75 |

| Oxycodone | 15 | 30 | 15 |

| Hydrocodone | — | 30 | — |

| Codeine | 130 | 200 | 130 |

| Tramadol | — | 350 | — |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree