Fig. 8.1

A possible algorithm/pathway for diagnosis and treatment of arrhythmias in patients with channelopathies

Table 8.1

Conditions that can cause PVT/VF and potential therapies

Clues | Test to consider | Diagnoses | Therapies |

|---|---|---|---|

Long QT/T wave alternans TdP History of seizures Specific triggers (loud noise) | ECG/monitor Epinephrine challenge Exercise stress test Genetic testing | Congenital LQTS | Beta-blockers Avoid QT-prolonging drugs In LQT3: mexiletine/flecainide PM/ICD Stellatectomy |

Incomplete RBBB with STE in leads V1–V2 Fever | ECG Drug challenge Genetic testing | BrS | Isoproterenol/quinidine Antipyretic Ablation ICD |

J-point elevation | ECG | Early repolarization | ICD |

Short QT interval | ECG | SQTS | ICD Quinidine or sotalol |

Bidirectional VT exercise induced | Exercise stress test Genetic testing | CPVT Andersen-Tawil syndrome | Beta-blockers/flecainide/verapamil ICD |

8.5 Indications for Hospitalization, Follow-Up, and Referral

Following the arrhythmic index event, channelopathy patient should be reevaluated for risk stratification and prevention of recurrences. Expert centers with a focus on inherited arrhythmias should be involved in complex cases [4].

Atrial arrhythmias in low-risk patients could be managed in out-of-hospital setting with referral to arrhythmia experts to set up indication for pharmacological or non-pharmacological strategy. Thromboembolism should be managed according to AF guidelines using CHA2DS2VASC score [20]. First line therapy consists in avoiding potentially pro-arrhythmic drugs and conditions: a complete list should be supplied to the patient and to the general practitioner.

CPVT and LQT patients should be advised to limit/avoid competitive sport, strenuous exercise, and exposure to stressful environments (which in LQT2 should include exposure to loud/abrupt noises, i.e., alarm bell); Brugada patients should avoid excessive alcohol intake and large meals and should be advised to a prompt treatment of fever [45].

Syncope and life-threatening arrhythmias require hospitalization.

Aborted sudden death and sustained ventricular arrhythmias require an ICD for secondary prevention [4, 15, 31, 45] with or without adjunctive therapy.

CPVT and LQTS patients should be treated with beta-blockers: nadolol and propranolol are the drugs of choice [1, 4, 33]; in patients with recurrent symptoms/arrhythmias already on beta-blockers, it should be considered flecainide for CPVT patients [33] and flecainide or ranolazine or mexiletine in LQT3 patients [4]; ICD and left cardiac denervation should be considered in patients refractory to pharmacological therapy [4, 33]. Repeated exercise stress test is used in CPVT patients to evaluate drug efficacy.

Brugada and SQTS patients symptomatic for syncope should be treated with ICD; quinidine therapy could be used as adjunctive therapy or in cases in which ICD is refused or contraindicated or in recurrent appropriate ICD intervention [22, 26].

All clinically diagnosed patients with LQTS and CPVT should undergo genetic evaluation if not previously performed, and it can be useful in Brugada (type1) patients and SQTS [42]. Routine genetic testing is not indicated for the survivor of an unexplained out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the absence of a clinical index of suspicion for a specific cardiomyopathy or channelopathy [42] (Figs. 8.2 and 8.3)

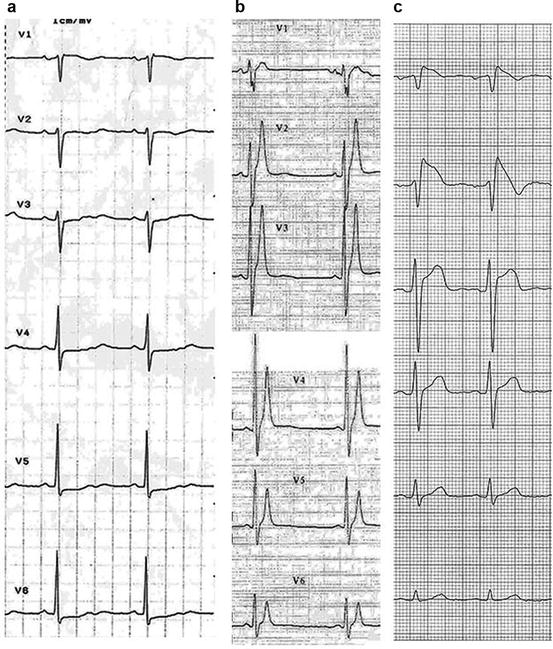

Fig. 8.2

Panel (a):12-lead ECG from a 9-year-old boy with ryanodine-positive CPVT shows a transition from triggered bidirectional ventricular tachycardia followed by brief polymorphic ventricular tachycardia to reentrant ventricular fibrillation. With permission from Elsevier Roses-Noguer F. et al. [43]: Copyright © 2014 Heart Rhythm Society. Panel (b): torsades de point. With permission from Van der Heide et al. [44]

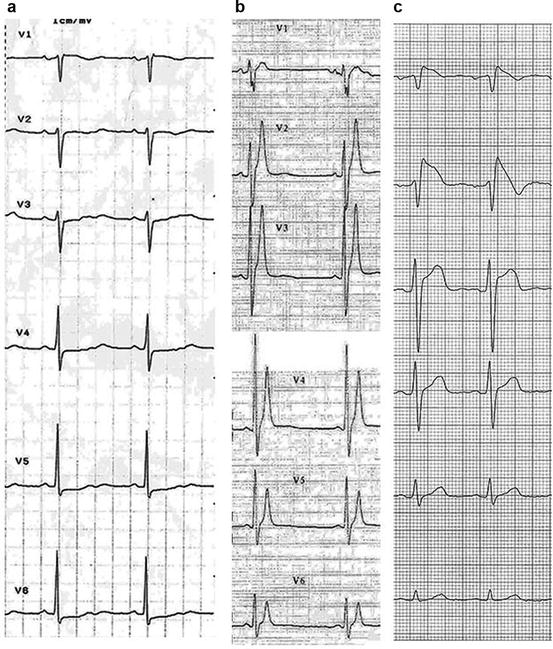

Fig. 8.3

Precordial leads ECG in patients with panel (a), long QT syndrome, heart rate 58 beats per minute, QTc 600 ms; panel (b), short QT syndrome, heart rate 52 beats per minute (bpm), QT 280 ms*; panel (c), Brugada syndrome, coved ST elevation in V1–V2. *With permission from Gaita F. et al. [7]

References

1.

2.

Patel C, Burke JF, Patel H, et al. Is there a significant transmural gradient in repolarization time in the intact heart? Cellular basis of the T wave: a century of controversy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(1):80–8.PubMedPubMedCentralCrossRef

3.

4.