Chapter 36 Acute gastrointestinal bleeding

Acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Peptic ulcer disease accounts for 75% of upper GI bleeding.1,2 Bleeding from varices, oesophagitis, duodenitis and Mallory–Weiss syndrome each account for between 5% and 15% of cases. About 20% of GI bleeding arises from the lower GI tract. Common aetiological causes for GI bleeding are listed in Table 36.1. Mortality from upper GI bleeding has remained at approximately 10% for decades, but recent reports suggest that mortality from bleeding ulcers has fallen substantially to about 5%.3 On the other hand, variceal bleeding has a much higher mortality of about 30%. Risk factors for mortality include old age, associated medical problems, coagulopathy and magnitude of bleeding.

Table 36.1 Common causes of acute gastrointestinal bleeding

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Peptic ulcers (DU:GU 3:1) |

| Varices (oesophageal varices:gastric varices 9:1) |

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy |

| Mallory–Weiss syndrome |

| Gastritis, duodenitis and oesophagitis |

| Lower gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Diverticular bleeding |

| Angiodysplasia and arteriovenous malformation |

| Colonic polyps or tumours |

| Meckel’s diverticulum |

| Inammatory bowel diseases |

DU, duodenal ulcer; GU, gastrointestinal ulcer.

UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

INVESTIGATION

ENDOSCOPY OR BARIUM STUDY

MANAGEMENT OF NON-VARICEAL UPPER GI BLEEDING

RESUSCITATION

Blood and plasma expanders should be given through large-bore intravenous cannulae. Vital signs should be closely monitored. In patients with hypovolaemic shock, central venous pressure and hourly urine output should also be observed (see Chapter 11). Following adequate resuscitation, management is directed to identify the lesion and distinguish the high-risk patient, who is likely to require early endoscopic or surgical treatment.

THE HIGH-RISK PATIENT

Significant GI bleeding is indicated by syncope, haematemesis, systolic blood pressure below 100 mmHg (13.3 kPa), postural hypotension and, if more than 4 units of blood have to be transfused in 12 hours, to maintain blood pressure. Patients over 60 years old and with multiple underlying diseases are at even higher risk.3 Those admitted for other medical problems (e.g. heart or respiratory failure, or cerebrovascular bleed) and who have GI bleeding during hospitalisation also have a higher mortality.

THE HIGH-RISK ULCER

Peptic ulcers that are actively bleeding or have bled recently may show stigmata of haemorrhage on endoscopy. These include localised active bleeding (i.e. pulsatile, arterial spurting or simple oozing), an adherent blood clot, a protuberant vessel or a flat pigmented spot on the ulcer base. Stigmata of haemorrhage are important predictors of recurrent bleeding (Table 36.2). The proximal postero inferior wall of the duodenal bulb and the high lesser curve of the stomach are common sites for severe recurrent bleeding, due probably to their respective large arteries (gastroduodenal and left gastric arteries).

Table 36.2 Stigmata of haemorrhage and risk of recurrent bleeding in peptic ulcers

| Stigmata of haemorrhage | % recurrent bleeding |

|---|---|

| Spurter or oozer | 85–90 |

| Protuberant vessel | 35–55 |

| Adherent clot | 30–40 |

| Flat spot | 5–10 |

| None | 5 |

TREATMENT

Pharmacological control

Acid-suppressing drugs such as H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are very effective drugs to promote ulcer healing. An acidic environment impairs platelet function and haemostasis. Therefore, reducing the secretion of gastric acid should reduce bleeding and encourage ulcer healing. A recent study has shown that potent acid suppression using intravenous proton pump inhibitors reduces recurrent bleeding after endoscopic therapy.4 Proton pump inhibitors should be recommended in high-risk peptic ulcer bleeding patients as an adjuvant to endoscopic therapy. In contrast, antifibrinolytic agents such as tranexamic acid have not been effective in reducing the operative rate and mortality of acute GI haemorrhage. Recent studies show that in patients at high risk of recurrent bleeding, pharmacologic control without endoscopic hemostasis is inadequate.5 Thus a combination of endoscopic and pharmacologic therapy offers the best therapy for ulcer bleeding patients.6,7

Endoscopic therapy

Adrenaline (epinephrine) injection

Endoscopic injection of adrenaline (1:10 000 dilution) at 0.5–1.0-ml aliquots (up to 10–15 ml) into and around the ulcer bleeding point has achieved successful haemostasis in over 90% of cases.6 Debate exists as to whether the haemostatic effect is a result of local tamponade by the volume injected, or vasoconstriction by adrenaline. Absorption of adrenaline into the systemic circulation has been documented, but without any significant effect on the haemodynamic status of the patient.8 Adrenaline injection is an effective, cheap, portable and easy-to-learn method of haemostasis, and has acquired worldwide popularity.

Coaptive coagulation

This method uses direct pressure and heat energy (heater probe) or electrocoagulation (bipolar coagulation probe (BICAP)) to control ulcer bleeding. The depth of tissue injury induced by these devices is minimised, as the bleeding vessel is tamponaded prior to coagulation. The overall efficacy of the adrenaline injection, heater probe and BICAP probe methods is comparable.9 Occasionally, it is not possible to obtain a view en face of the bleeding ulcers, particularly those on the lesser curve or on the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb. In these situations, direct pressure cannot be applied, and the failure rate of coaptive coagulation in these situations is expected to be higher.

Haemoclips

Endoscopic clipping of a bleeding vessel is an appealing alternative treatment which has gained popularity in recent years. The advantage of haemoclips over thermocoagulation is that there is no tissue injury induced and hence the risk of perforation is reduced. Studies comparing haemoclips against injection and thermocoagulation have shown favourable results.10,11 However, the application of haemoclips in certain sites, for example lesser curve, gastric fundus and posterior wall of the duodenum, is technically difficult. Loading of clips on to the application device is cumbersome and time-consuming and transfer of torque from the handle to the tip of the device is limited.

SURGERY

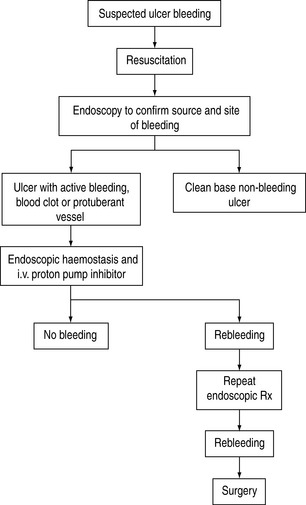

Surgical procedures include underrunning of the ulcer, underrunning plus vagotomy and drainage, and various types of gastrectomy. The overall mortality of emergency surgery for GI bleeding is about 15–20%. In a study investigating the best salvage treatment for patients with recurrent bleeding after endoscopic therapy, surgery was found to be comparable to repeating endoscopic treatment in securing hemostasis.12 However, morbidity is significantly higher in surgical patients than in endoscopic patients. Early surgery should be considered in patients with hypovolaemic shock and/or large peptic ulcer with protuberant vessels. A protocol to manage bleeding peptic ulcer is shown in Figure 36.1.13

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree