Chapter 64

Acute Central Nervous System Infections

Epidemiology and Etiology

Bacterial Central Nervous System Infections

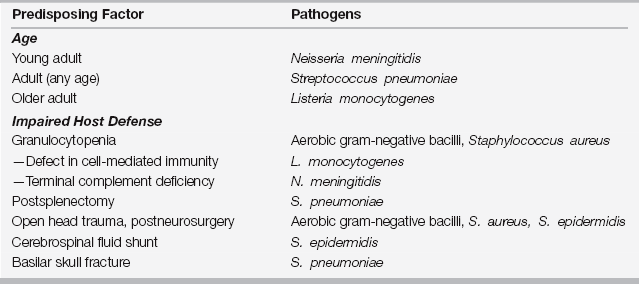

Uncomplicated adult bacterial meningitis in the United States is primarily due to Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis. However, many factors influence the likelihood of infection with other organisms (Table 64.1). Splenectomy, immunoglobulin deficiency, pneumococcal pneumonia, alcoholism, chronic liver or renal disease, diabetes mellitus, and cerebrospinal fluid leaks all predispose the patient to infection with S. pneumoniae. Agents causing meningitis in the postneurosurgical or head trauma setting include staphylococci and gram-negative bacilli. Listeria monocytogenes should be considered in persons with a defect in cell-mediated immunity (e.g., solid organ transplant, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection, chronic corticosteroid use, Hodgkin disease), as well as in alcoholics, the elderly, and persons with iron overload, chronic liver or renal disease, and diabetes.

Clinical Presentation and Complications

Most patients with acute viral meningitis present with fever, headache, and nuchal rigidity. The headache is typically severe and either frontal or diffuse. Photophobia is also common. Meningismus limits head flexion but not rotation. In contrast, both flexion and rotation are limited in patients with cervical arthritis, Parkinson disease, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Additional symptoms might include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and myalgias. Patients with viral meningitis are usually uncomfortable but do not appear toxemic. Although most patients have a nonspecific presentation, associated clinical clues to the cause might include an enteroviral exanthem, mumps parotitis, or herpes genitalis. The duration of viral meningitis is generally less than a week, and it usually resolves without sequelae.

General Diagnostic Approach

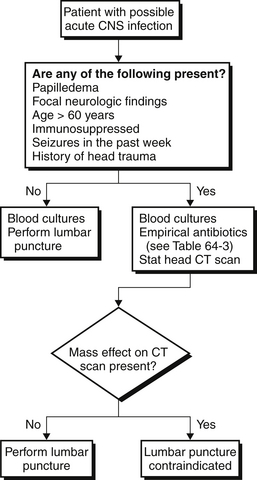

In most patients, the presentation of an acute meningitis is sufficiently distinct from the presentation of a CNS mass lesion that imaging before a lumbar puncture is unnecessary and might potentially delay therapy (Figure 64.1). A number of historical and physical examination findings have been shown to increase the likelihood of a CNS mass lesion and should prompt either computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain before lumbar puncture. These include age > 60, immunosuppressed state, recent seizure, altered mental status, papilledema, focal neurologic findings, or evidence of head trauma. If meningitis is a consideration but the presence of any of these findings suggest the possibility of a focal CNS problem, antibiotic therapy should not be delayed while obtaining CNS imaging studies before lumbar puncture. In addition to the initial tests mentioned earlier, several milliliters of CSF should be saved in a refrigerator pending the results of these initial tests in case further testing is needed. Generally the results of the initial tests reflect whether or not the process is bacterial (Figure 64.2). If bacterial meningitis is not diagnosed, this reserved fluid can be tested for other pathogens.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree