INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

More adult patients visit the ED for “stomach and abdominal pain, cramps, or spasms” than for any other chief complaint. Demographics (age, gender, ethnicity, family history, sexual orientation, cultural practices, geography) influence both the incidence and the clinical expression of abdominal disease. History, physical examination, and laboratory studies can be helpful, but imaging is often required to make a specific diagnosis. Clinical suspicion for serious disease is especially important for patients in high-risk groups.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Abdominal pain is divided into three neuroanatomic categories: visceral, parietal, and referred.

Obstruction, ischemia, or inflammation can cause stretching of unmyelinated fibers that innervate the walls or capsules of organs, resulting in visceral pain. Visceral pain is often described as “crampy, dull, or achy,” and it can be either steady or intermittent (colicky). Because the visceral afferent nerves follow a segmental distribution, visceral pain is localized by the sensory cortex to an approximate spinal cord level determined by the embryologic origin of the organ involved (Table 71-1).

| Embryologic Origin | Involved Organs | Location of Visceral Pain |

|---|---|---|

| Foregut | Stomach, first/second parts of duodenum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas | Epigastric area |

| Midgut | Third/fourth parts of duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, first two thirds of transverse colon | Periumbilical area |

| Hindgut | Last one third of transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid, rectum, intraperitoneal GU organs | Suprapubic area |

Because intraperitoneal organs are bilaterally innervated, stimuli are sent to both sides of the spinal cord, causing intraperitoneal visceral pain to be felt in the midline, independent of its right- or left-sided anatomic origin. For example, stimuli from visceral fibers in the wall of the appendix enter the spinal cord at about T10. When obstruction causes appendiceal distention in early appendicitis, pain is initially perceived in the midline periumbilical area, corresponding roughly to the location of the T10 cutaneous dermatome.

Parietal (somatic) abdominal pain is caused by irritation of myelinated fibers that innervate the parietal peritoneum, usually the portion covering the anterior abdominal wall. Because parietal afferent signals are sent from a specific area of peritoneum, parietal pain—in contrast to visceral pain—can be localized to the dermatome superficial to the site of the painful stimulus. As the underlying disease process evolves, the symptoms of visceral pain give way to the signs of parietal pain, causing tenderness and guarding. As localized peritonitis develops further, rigidity and rebound appear. Patients with peritonitis generally prefer to remain immobile.

Referred pain is felt at a location distant from the diseased organ. Referred pain patterns are also based on developmental embryology. For example, the ureter and the testes were once anatomically contiguous and therefore share the same segmental innervations. Thus acute ureteral obstruction is often associated with ipsilateral testicular pain. Referred pain is usually perceived on the same side as the involved organ, because it is not mediated by fibers that provide bilateral innervation to the cord. Referred pain is felt in the midline only if the pathologic process is also located in the midline.

CLINICAL FEATURES

To determine the urgency and method of the diagnostic approach, we recommend the use of a pragmatic scheme based on patient acuity and the identification of risk factors.

Patient Acuity: Is this patient critically ill? If so, simultaneously resuscitate and evaluate.

Risk Factors: Are there special conditions or risk factors that affect clinical risk or mask the disease process?

Critically ill patients need immediate stabilization. Markers of high acuity include extremes of age, severe pain of rapid onset, abnormal vital signs, dehydration, and evidence of visceral involvement (e.g., pallor, diaphoresis, vomiting). The intensity of abdominal pain may bear no relationship to the severity of illness. Serious illness may be present even if vital signs are normal, particularly in high-risk groups such as the elderly and the immunocompromised. Shock that develops rapidly after the onset of acute abdominal pain is usually the consequence of intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Systolic pressure does not drop until blood loss reaches 30% to 40% of normal blood volume. Tachycardia is a useful parameter for the assessment of volume depletion, but its absence does not exclude blood/fluid loss. If pulse and blood pressure are in the normal range but there is reason to suspect intravascular volume depletion, obtain orthostatic vital signs. An increase in pulse rate of 30 beats/min after standing for 1 minute (or near-syncope that develops with a lesser increase) represents the loss of a liter of blood or its equivalent (a 20% blood loss for an average adult; roughly 3 L of normal saline).1 The presence of orthostatic tachycardia is useful, but its absence does not exclude severe bleeding. Orthostatic hypotension is a later finding, representing the failure of sympathetic reflex tachycardia to maintain cardiac output. The threshold of 20 points of pulse change may not be applicable to patients on medications such as β-blockers, diabetic patients (who may have autonomic neuropathy), and the elderly (due to the effects of aging on the cardiac conduction system). “Orthostatics” should not be performed in patients who are already hypotensive. Tachypnea may indicate a cardiopulmonary process, metabolic acidosis, anxiety, or pain. Temperature is neither sensitive nor specific for disease process or patient condition. The presence or absence of fever cannot be used to distinguish surgical from medical disease.

Resuscitation of the critically ill patient with abdominal pain includes a cardiac monitor, oxygen (2 to 4 L/min via nasal cannula or mask), large-bore IV access, and an isotonic fluid bolus adjusted for age, weight, and cardiovascular status. For critically ill patients, blood samples should be drawn at the time of IV insertion, including, at a minimum, electrolytes, BUN and creatinine, CBC with platelets, clotting studies, and a type and antigen screen of blood. Order cross-matched blood if hemorrhage is suspected or if urgent transfusion is anticipated. In the presence of circulatory collapse, visualization of an enlarged aorta is taken as de facto evidence of leakage or rupture, requiring immediate surgery. Bedside ED US can visualize and measure the abdominal aorta.2,3 Perform bedside US to identify abdominal aortic aneurysm and perform FAST if intra-abdominal hemorrhage is suspected.2,3

Risk Factors: Are There Special Conditions or Risk Factors That Affect Clinical Risk or Mask the Disease Process?

Identify pertinent past medical illness (diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, liver disease, renal disease, human immunodeficiency virus status, sexually transmitted diseases), previous abdominal surgeries, pregnancies and menstrual history (deliveries, abortions, ectopics), medications (steroids, immune suppressants, acetylsalicylic acid/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, laxatives, narcotics, fertility agents, intrauterine devices, chemotherapeutic agents), allergies, and any recent trauma. Ask about previous episodes of similar abdominal pain, diagnostics, and treatments. Review previous medical records. Obtain a social history that includes habits (tobacco, alcohol, other drug use), occupation, possible toxic exposures, and living circumstances (homeless, dwelling heated, running water, living alone, other family members ill with similar symptoms).

A number of conditions camouflage critical illness in patients with acute abdominal pain. High-risk groups include patients with cognitive impairment secondary to dementia, intoxication, psychosis, mental retardation, or autism; patients who cannot communicate effectively because of aphasia or language barriers; patients in whom physical or laboratory findings may be minimal (the elderly) or obscured (patients with spinal cord injury); asplenic patients; neutropenic patients; transplant patients; patients whose immune systems are impaired by illness (human immunodeficiency virus; chronic renal disease; diabetes, cirrhosis, hemoglobinopathy; malnutrition, chronic malignancy, autoimmune disease, mycobacterial infection); and patients taking immune-suppressive or immune-modulating medications, such as steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, antimetabolic agents, monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies, and chemotherapeutic agents.

In general, patients with mild to moderate immune dysfunction have delayed or atypical presentations of common diseases. Patients with severe immune dysfunction are more likely to present with opportunistic infections. The CD4 count is the most important measure of immune competency in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Patients with CD4 counts over 200/mm3 are much less likely to have opportunistic infections.

Obtain a clear description of the pain itself (PPQRSTT: provocative/palliative factors, quality, radiation, associated symptoms, timing, and what the patient has taken for the pain).

Before the complete physical examination, take a few moments to gain the patient’s trust by explaining what needs to be done, exposing only what needs to be seen, and re-covering exposed parts of the body sequentially. Provide patient privacy. Note the patient’s skin (color, temperature, turgor, perfusion status), and perform a targeted heart and lung examination.

Inspect the abdomen for signs of distention (ascites, ileus, obstruction, volvulus), obvious masses (hernia, tumor, aneurysm, distended bladder), surgical scars (adhesions), ecchymoses (trauma, bleeding diathesis), and stigmata of liver disease (spider angiomata, caput medusa).

Bowel sounds are nonspecific diagnostic signs. Decreased bowel sounds suggest ileus, mesenteric infarction, narcotic use, or peritonitis. Hyperactive bowel sounds may be noted in small bowel obstruction.

Liver size can be estimated by the presence of percussion dullness in the midclavicular line, except in cases of severe bowel distention. A fluid wave may suggest ascites, and tympany may suggest dilated loops of bowel.

The vast majority of clinical information is acquired through gentle palpation, using the middle three fingers, and saving the painful area for last. Voluntary guarding (contraction of the abdominal musculature in anticipation of or in response to palpation) can be diminished by asking patients to flex the knees. Those who remain guarded after this maneuver will often relax if the clinician’s hand is placed over the patient’s, and the patient is then asked to use his or her own hand to palpate the abdomen. Distracting the patient with conversation may divert attention from the examination. Optimally, the patient’s tenderness will be confined to one of the four traditional abdominal quadrants (right upper, right lower, left upper, left lower), and pain location can be used to generate a differential diagnosis. Often, this is not the case, and one finds more diffuse tenderness involving one or more of the four abdominal quadrants. Peritoneal irritation is suggested by rigidity (involuntary guarding or reflex spasm of abdominal muscles), as is pain referred to the point of maximum tenderness when palpating an adjacent quadrant. Rebound tenderness, often regarded as the sine qua non for peritonitis, has several important limitations. In patients with peritonitis, the combination of rigidity, referred tenderness, and pain with coughing usually provides sufficient diagnostic confirmation that little additional information is gained by eliciting the unnecessary pain of rebound. More than one third of patients with surgically proven appendicitis do not have rebound tenderness.4 False positives occur without peritonitis, perhaps due to a nonspecific startle response. One might reasonably question whether rebound has sufficient predictive value to justify the discomfort it causes patients.

Evaluate the abdominal aorta, particularly in patients >50 years of age with acute abdominal, flank, or low back pain. Palpation cannot reliably exclude abdominal aortic aneurysm, and the presence or absence of femoral pulses is generally not helpful in the clinical diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm.

It is wise to perform a pelvic examination in the evaluation of lower abdominal pain in women of reproductive age who have not had a complete hysterectomy. The presence of peritoneal signs, cervical motion tenderness, and unilateral or bilateral abdominal and/or pelvic tenderness suggests pelvic infection, or ectopic gestation in pregnant women. In males, hernia, testicular, and prostate examinations are indicated because disorders of these structures can cause lower abdominal pain.

The rectal examination does not increase diagnostic accuracy beyond what has already been obtained by other components of the physical examination. The main value of the rectal examination is the detection of grossly bloody, maroon, or melanotic stool.

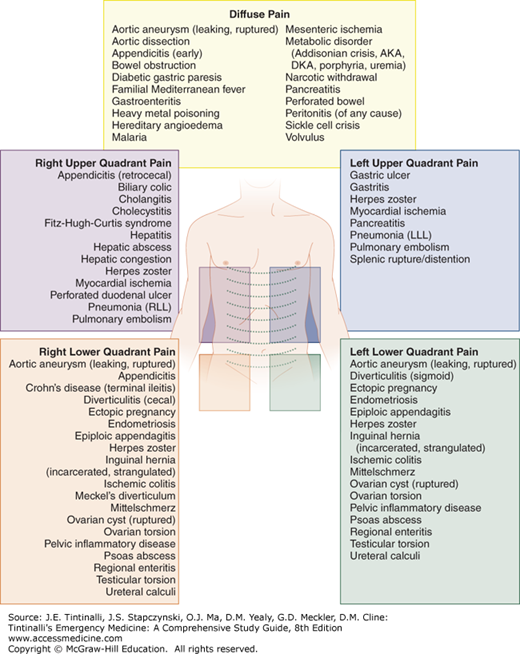

One common approach to the evaluation of acute abdominal pain is to use the location of the pain (diffuse, right upper quadrant, right lower quadrant, left upper quadrant, left lower quadrant) to guide the generation of a differential diagnosis (Figure 71-1).5

Alternatively, abdominal crises may be grouped according to presenting symptomatology: pain, vomiting, abdominal distention, muscular rigidity, and/or shock (Table 71-2).

| Pain/vomiting/ ± rigidity | Pain/vomiting/distention | Pain (± vomiting) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute pancreatitis | Bowel obstruction | Acute diverticulitis |

| Diabetic gastric paresis | Cecal volvulus | Adnexal torsion |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | Mesenteric ischemia | |

| Incarcerated hernia | Myocardial ischemia* Testicular torsion | |

| Pain/shock | Pain/shock/rigidity | Distention (± pain) |

| Abdominal sepsis | Perforated appendix | Elderly with bowel obstruction/volvulus |

| Aortic dissection | Perforated diverticulum | |

| Hemorrhagic pancreatitis | Perforated ulcer | |

| Leaking/ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm | Ruptured esophagus Splenic rupture | |

| Mesenteric ischemia (late) | ||

| Myocardial ischemia* | ||

| Ruptured ectopic pregnancy |

Although the location of the patient’s pain and the grouping of symptoms can both help to differentiate among known diseases, clinical suspicion and an understanding of the individual is paramount, because the causes of acute abdominal pain vary considerably with patient demographics. For example, older adults are more likely than younger adults to have biliary disease, diverticulitis, and bowel obstruction. Appendicitis occurs more commonly in younger adults. In the words of Sir William Osler, it is important to know “what sort of patient has the disease.”

SYMPTOM TREATMENT AND FURTHER CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

At this point, provide symptomatic relief. Opioid analgesia relieves pain and will not obscure abdominal findings, delay diagnosis, or lead to increased morbidity/mortality.6,7 Do not withhold analgesia from patients with acute undifferentiated abdominal pain. The information on the safety of opioids cannot be extrapolated to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as parenteral ketorolac because nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are not pure analgesics and can mask early peritoneal inflammation.

Administer antiemetics as needed. A Cochrane review8 reported that ondansetron and metoclopramide reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree