INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Acetaminophen (N-acetyl-p-aminophenol or paracetamol) is the most popular over-the-counter analgesic and is one of the most common toxic exposures reported to poison centers. Acetaminophen is available as a sole agent or combined with a variety of other medications prepared in many different forms, such as tablets, capsules, gels, and liquids. Poisonings often occur because of the erroneous belief that this medication is benign or because the victim was unaware that acetaminophen was an ingredient in the ingested preparation.1 The U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group found that acetaminophen poisoning was the cause of acute liver failure in 18% of cases initially judged to be of unknown cause.2 Acetaminophen–opioid combination products have been implicated in chronic overuse, likely due to an increasing opioid requirement leading to concomitantly increasing acetaminophen exposure. In response to these safety concerns, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently limited the prescription acetaminophen–opioid combination preparation strength to 325 milligrams per dosage unit and now requires a boxed warning to notify consumers of the potential risk for serious liver toxicity.3

During 2010, the American Association of Poison Control Centers received reports of 66,473 exposures to acetaminophen–opioid combinations and 73,307 exposures to acetaminophen alone.4 There were 65 deaths attributed to isolated ingestions of acetaminophen combinations and 60 deaths attributed to isolated acetaminophen ingestions.4 Combining ED, hospital, and poisoning databases, an estimated 450 deaths occur each year in the United States due to acetaminophen overdose, and approximately 100 of them are unintentional, primarily due to supratherapeutic dosing of child preparations.5

PHARMACOLOGY AND DOSING

The recommended maximum total daily dose is 3900 milligrams in adults using 325-milligram acetaminophen (regular strength) and 3000 milligrams when using the 500-milligram acetaminophen (extra strength) preparation. Adults should not use acetaminophen for more than 10 consecutive days unless directed by their physician. For children, the recommended acetaminophen dose is 10 to 15 milligrams/kg every 4 to 6 hours as needed, with a maximum daily dose of 75 milligrams/kg or five doses in a 24-hour period. In 2011, the infant acetaminophen formulation (80 milligrams/0.8 mL concentration) was discontinued to minimize the risk for medication error. All pediatric, both infant and child, acetaminophen liquid preparations are now standardized to a concentration of 160 milligrams/5 mL.

Patients with insufficient glutathione stores (e.g., alcoholics and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients) and patients with induced cytochrome P-450 enzymatic activity (e.g., alcoholics and those taking concurrent anticonvulsant or antituberculous medications) may be at greater risk for developing acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity following overdose (as opposed to therapeutic dosing described earlier). Although the evidence supporting this risk is not definitive, it may be prudent to reduce acetaminophen dosage for this population. In contrast, children, because of their greater ability to metabolize acetaminophen through hepatic sulfation, may be at decreased risk for developing hepatotoxicity following a moderate overdose.6,7

After ingestion of therapeutic doses, acetaminophen is rapidly absorbed from the GI tract, and peak serum concentrations are usually achieved within 30 minutes to 2 hours. In an overdose, peak serum concentrations are usually achieved within 2 hours, but delayed absorption of acetaminophen occurs following overdoses of preparations in which acetaminophen is combined with propoxyphene or diphenhydramine, as well as those with altered-release kinetics such as extended-release preparations.8,9,10,11 In therapeutic amounts, acetaminophen has nearly 100% bioavailability, is approximately 20% bound to serum proteins, has a volume of distribution of around 0.85 L/kg, and has an elimination half-life of approximately 2.5 hours. The therapeutic concentration for the antipyretic effect of acetaminophen is between 10 and 20 micrograms/mL (66 to 132 micromoles/L), but therapeutic concentrations for analgesia are not established.

Oral acetaminophen appears to be nontoxic when administered following therapeutic dosing guidelines. Both retrospective and prospective studies have yielded inconsistent results concerning the risk of acute liver injury with repeated use of therapeutic acetaminophen doses.12 The prospective studies, which are better controlled than the retrospective ones, find a slight increase in liver injury but no evidence of increased hepatic failure or death when using therapeutic acetaminophen doses for sustained periods.13 For alcoholic patients, no evidence of liver injury was seen when treated with the recommended maximal daily dose of acetaminophen for 3 consecutive days.14,15

An IV acetaminophen formulation was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2010 for adults and children 2 years of age or older. The recommended dosing of IV acetaminophen for adults or children weighing more than 50 kg is 650 milligrams every 4 hours or 1000 milligrams every 6 hours, with a maximum total daily dose of 4 grams. For adults or children weighing less than 50 kg, the recommended dosing is 12.5 milligrams/kg every 4 hours or 15 milligrams/kg every 6 hours (maximum individual dose of 750 milligrams), with a maximum total daily dose of 75 milligrams/kg or 3750 milligrams. Peak concentrations following IV administration occur at the end of the 15-minute infusion period.16 Compared to a similar dose of oral acetaminophen, IV acetaminophen achieves a 70% greater maximum concentration but provides a similar total drug exposure.16

In therapeutic amounts, acetaminophen is primarily metabolized by the liver through sulfation (20% to 46%) and glucuronidation (40% to 67%), with <5% undergoing direct renal elimination. Normally, a small percentage is also oxidized by the cytochrome P-450 system to a reactive metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI). This is quickly detoxified by hepatic glutathione to a nontoxic acetaminophen-mercapturate compound that is renally eliminated (Figure 190-1). After acetaminophen overdose, hepatic metabolism through glucuronidation and sulfation may be saturated, and a larger proportion of acetaminophen is therefore metabolized by cytochrome P-450 to NAPQI, depleting intracellular glutathione. When hepatic stores of glutathione decrease to <30% of normal, NAPQI binds to other hepatic macromolecules, and hepatic necrosis ensues. Although the clinical manifestations of acetaminophen toxicity are classically delayed, hepatic injury actually occurs early, within 12 hours of exposure.

FIGURE 190-1.

Acetaminophen metabolism. A. After ingestion of therapeutic amounts, predominant metabolism is via glucuronidation and sulfation. The small amount of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI) generated is conjugated with glutathione to a nontoxic compound. B. After ingestion of large amounts, glucuronidation and sulfation are saturated, and an increased amount of NAPQI is generated. Detoxification of NAPQI to a nontoxic compound soon depletes glutathione stores, leaving excess NAPQI to bind to intracellular proteins, causing cell death. APAP = N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (acetaminophen).

Within the hepatic lobule, cytochrome P-450 is concentrated within hepatocytes surrounding the terminal hepatic vein and is least concentrated within hepatocytes surrounding the portal triad. As a result, acetaminophen-induced hepatic injury develops in the characteristic pattern of centrilobular necrosis. Hepatic injury can be identified by microscopic evidence as well as immunofluorescent staining of NAPQI-hepatic protein adducts within hepatocytes. Observed hepatocyte damage typically progresses with cell lysis on the second day after an acute toxic exposure, releasing hepatic enzymes, such as transaminases, and NAPQI-hepatic protein adducts into the circulation where they are detecTable in the serum. This corresponds generally to the development of overt clinical toxicity.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF ACETAMINOPHEN TOXICITY

The initial clinical findings of acetaminophen toxicity are nonspecific and delayed in onset.

The clinical presentation of human acetaminophen poisoning can be roughly divided into four stages (Table 190-1). During the first 24 hours after exposure (stage 1), patients often have minimal and nonspecific symptoms of toxicity, such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and malaise. Hypokalemia and metabolic acidosis may be seen during the first 24 hours and correlate with a high 4-hour acetaminophen concentration.17,18,19,20 By days 2 to 3 (stage 2), symptoms seen in stage 1 often improve, but clinical signs of hepatotoxicity may occur, including right upper quadrant abdominal pain and tenderness, with elevated serum transaminases. Even without treatment, most patients with mild to moderate hepatotoxicity recover without sequelae. However, by days 3 to 4 (stage 3), some patients will progress to fulminant hepatic failure.21,22 Characteristic stage 3 findings include metabolic acidosis, coagulopathy, renal failure, encephalopathy, and recurrent GI symptoms. Patients who survive the complications of fulminant hepatic failure begin to recover over the next 2 weeks (stage 4), with complete resolution of hepatic dysfunction in survivors after 1 to 3 months.

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing | First 24 h | Days 2–3 | Days 3–4 | After day 5 |

| Clinical manifestations | Anorexia Nausea Vomiting Malaise | Improvement in anorexia, nausea, and vomiting Abdominal pain Hepatic tenderness | Recurrence of anorexia, nausea, and vomiting Encephalopathy Anuria Jaundice | Clinical improvement and recovery (7–8 d) or Deterioration to multi-organ failure and death |

| Laboratory abnormalities | Hypokalemia | Elevated serum transaminases Elevated bilirubin and prolonged prothrombin time if severe | Hepatic failure Metabolic acidosis Coagulopathy Renal failure Pancreatitis | Improvement and resolution or Continued deterioration |

Acetaminophen may also cause acute, extrahepatic toxic effects, presumably because of the presence of cytochrome P-450 or similar enzymes (e.g., prostaglandin H synthase) in other organs. Ingestion of massive doses of acetaminophen (e.g., 4-hour acetaminophen concentrations >800 micrograms/mL or >5300 micromoles/L) is associated with the altered sensorium and a metabolic acidosis with an elevated lactate that can occur in the absence of either liver failure or hypotension.23 Renal insufficiency occurs in 1% to 2% of patients following acetaminophen overdose, usually after hepatic failure is evident.24,25,26 In rare cases, isolated renal injury, cardiac toxicity, and pancreatitis may occur.27,28

DIAGNOSIS

Acute acetaminophen poisoning is diagnosed by the serum acetaminophen concentration and estimating the time since ingestion.

A toxic exposure to acetaminophen is suggested when a patient ≥6 years old ingests (1) >10 grams or 200 milligrams/kg as a single ingestion, (2) >10 grams or 200 milligrams/kg over a 24-hour period, or (3) >6 grams or 150 milligrams/kg per 24-hour period for at least 2 consecutive days. For children <6 years old, ingestion of 200 milligrams/kg or more of acetaminophen as a single ingestion or over an 8-hour period, or of 150 milligrams/kg per 24-hour period for the preceding 48 hours is considered a toxic exposure. These values are empiric and not validated in human trials, but they are widely used as recommendations for emergency evaluation. Even though a patient’s history of the amount ingested may be unreliable, a patient report of >10 to 12 grams ingested was associated with a 4-hour acetaminophen concentration above 150 micrograms/mL (1000 micromoles/L) in 40% to 70% of toxic exposures.29,30

Due to the widespread availability of acetaminophen-containing products, the delayed clinical manifestations after overdose, and the serious complications of acute toxicity without antidotal therapy, measurement of a serum acetaminophen concentration is recommended for all patients presenting to the ED with an intentional overdose.31,32 Potentially toxic acetaminophen levels have been seen in ED overdose patients who denied ingesting acetaminophen.33,34 Empirical testing of all patients with intentional overdoses may be cost-effective, as the estimated cost of treating a single patient for complications of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity is judged to outweigh the cost of routine laboratory testing all intentional overdose patients. A qualitative acetaminophen urine screen can also be used to identify potential acetaminophen overdose patients.35

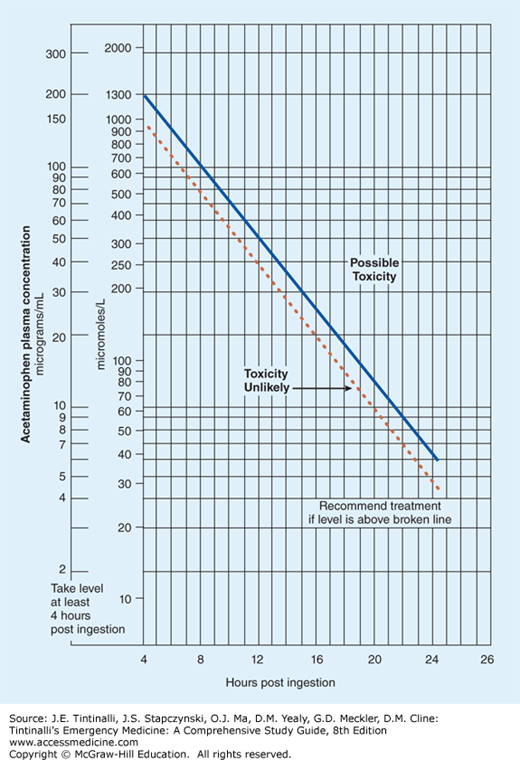

The implication of a measured acetaminophen concentration is determined by plotting the value on the Rumack-Matthew nomogram (Figure 190-2).36 This nomogram was derived from a retrospective analysis of oral acetaminophen overdose patients and their clinical outcomes. The original nomogram line separating possible toxicity from unlikely toxicity was based on a 4-hour acetaminophen concentration of 200 micrograms/mL (1300 micromoles/L), but was subsequently modified by moving the line to a 4-hour acetaminophen concentration of 150 micrograms/mL (1000 micromoles/L) to increase the safety margin for treatment decisions. The nomogram only directly applies to an acetaminophen concentration obtained after a single oral exposure and during the window between 4 hours and 24 hours postingestion. Outcome prediction using this nomogram cannot be applied to acetaminophen concentrations obtained outside this 20-hour window or with chronic or recurrent exposures. Obtaining multiple acetaminophen concentrations following acute overdose is rarely indicated in the absence of hepatotoxicity.37,38 An initial concentration below the nomogram line may rarely “cross the line” in patients who ingest acetaminophen preparations known to have prolonged absorption kinetics.11 However, the clinical significance of “crossing the line” in this fashion is unknown. Similarly, because the nomogram was constructed and verified by using only a single serum concentration, the clinical implications of a concentration above the line that falls below it on repeat analysis are unknown.

Based on data obtained before the widespread use of antidotal therapy, patients with serum acetaminophen concentrations above the original line (4-hour postingestion concentration >200 micrograms/mL or >1300 micromoles/L) were observed to have a 60% risk of developing hepatotoxicity (defined as alanine aminotransferase >1000 IU/mL), a 1% risk of renal failure, and a 5% risk of mortality.39 In addition, patients with extremely high serum acetaminophen concentrations (above a parallel line coinciding with a 4-hour postingestion concentration of 300 micrograms/mL or 2000 micromoles/L) were observed to have a 90% risk of developing hepatotoxicity. The prediction of a safe outcome below the nomogram line corresponding to a 4-hour postingestion concentration of 150 micrograms/mL (1000 micromoles/L) was confirmed in patients who did not receive antidotal therapy; the incidence of hepatotoxicity in patients with acetaminophen concentrations below this nomogram line was 1%, and all patients recovered without complications.38

A method to determine potential toxicity from IV acetaminophen overdose has not been established. Fortunately, the European experience with IV acetaminophen suggests that these overdoses appear to be rare in-hospital occurrences that are likely to occur following an error in calculating the acetaminophen dose in pediatric patients.40,41,42 However, the available clinical data for evaluating IV acetaminophen overdose remain limited to several published case reports.42 Because the Rumack-Matthew nomogram was solely derived from oral acetaminophen overdose patients, strictly applying the nomogram to determine toxicity following IV acetaminophen overdose may not be appropriate at this time.

TREATMENT

Treatment of acetaminophen poisoning consists primarily of the timely use of the antidote acetylcysteine and supportive care.1,36,37 For most cases of acetaminophen poisoning, adequate GI decontamination consists of the early administration of activated charcoal orally or through a nasogastric tube.1,43,44

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree