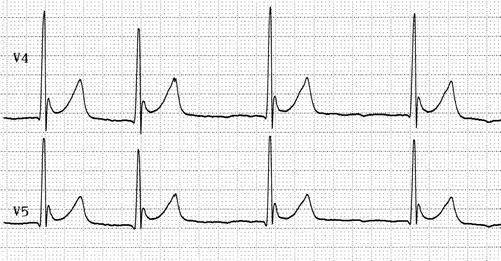

Fig. 9.1

Classic electrocardiogram findings in hypothermia. This EKG demonstrates three common findings in hypothermia, including bradycardia, shivering artifact, and J-waves (Image courtesy of lifeinthefastlane.com)

Question

What is the next best step in rewarming this patient?

Answer

Initiate rewarming via extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR)

When pulse and signs of life are absent in hypothermia, treatment with extracorporeal rewarming with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is recommended. ECMO can be initiated in two modes: veno-venous (VV) or veno-arterial (VA) depending on the presence of innate and preserved cardiac function. This hospital has cardiac surgery available and consultation with the surgeon is necessary to determine which modality is best for the patient. Due to ongoing CPR, the decision was made to initiate VA ECMO with percutaneous venous and arterial cannulation at the bedside. The heater on the ECMO circuit was set to 37 °C and rewarming was started as soon as cannulation was complete. CPR continued until the patient was rewarmed to 30 °C, at which point defibrillation was again attempted with successful conversion to normal sinus rhythm. After 4 h of ECMO, his temperature and blood pressure had normalized. Repeat arterial blood gas on FiO2 0.5 was: pH 7.38, paCO2 39 mmHg, paO2 92 mmHg, bicarbonate 22.6 mmol/L, base deficit −2.2, SaO2 99 %, potassium 3.7 mmol/L, and hemoglobin 10.5 mmol/L. He received broad-spectrum antibiotics for high likelihood of aspiration and continued warm IV fluids due to presumed cold diuresis. After 24 h, the patient was awake and following commands with no evidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome. ECMO support was stopped and the patient was extubated the following day without incident. Neurologic exam was normal. He developed AKI requiring 3 days of dialysis, but had complete renal recovery. He was discharged home after 1 week with no functional or neurologic impairment.

Principles of Management

Diagnosis

Hypothermia is defined as a core body temperature of less than 35 °C (95 °F) and is classified by severity; mild, moderate, or severe (Table 9.1) [1]. Standard thermometers do not read below 34 °C, therefore, accurate measurement of core temperature should be obtained by esophageal, bladder, or rectal probes [2]. If core temperature cannot be readily measured, the Swiss staging system (Table 9.2) can be used to guide management based on clinical symptoms [3]. Additional risk factors for development of accidental hypothermia include extremes of age, ethanol abuse, and malnutrition [2].

Table 9.1

Classification of hypothermia

Mild | 35–32 °C |

Moderate | <32 to 28 °C |

Severe | <28 to 24 °C |

Table 9.2

Swiss staging system of hypothermia

Stage | Clinical symptoms |

|---|---|

I | Conscious, shivering |

II | Altered mental status, no shivering |

III | Unconscious, no shivering |

IV | No vital signsa |

With cold exposure, the body attempts to increase heat production by increasing circulating epinephrine, which leads to tachycardia, increased minute ventilation, peripheral vasoconstriction, and shivering [4]. If exposure persists, these compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed, resulting in decreased metabolic demand, cessation of shivering, and ultimately death [3]. The effects of hypothermia by organ system are summarized in Table 9.3 and represent typical clinical findings.

Table 9.3

Clinical findings in hypothermia

Organ system | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|---|

Neurologic | Apathy Confusion Ataxia | Dilated pupils Paradoxical undressing Stupor | Areflexia Coma |

Cardiovascular | Tachycardia | Bradycardia Atrial fibrillation Hypotension | Ventricular dysrhythmias Asystole |

Pulmonary | Tachypnea | Bradypnea | Pulmonary edema |

Renal | High urine output | High urine output | Oliguria |

Metabolic | Hyperglycemia No shivering Respiratory alkalosis | Variable blood glucose Shivering Mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis | Hypoglycemia No shivering Mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis |

Finally, any underlying medical conditions that may have contributed to development of hypothermia should be obtained by a focused history and physical exam. These include trauma, infection, toxic ingestion, endocrinopathy (e.g. myxedema coma), metabolic derangements, and stroke [1].

Patient Monitoring

Due to the dramatic hemodynamic changes that can occur with hypothermia and rewarming, all patients should be closely monitored with telemetry, continuous pulse oximetry, frequent blood pressure checks, and core temperature probe [3]. Pulse oximetry is often difficult to measure due to peripheral vasoconstriction and arterial blood gas may be the only way to assess oxygen content. There is also limited data to suggest that forehead pulse oximetry may be more accurate than fingertip devices in hypothermia [5]. The authors recommend pre-emptive placement of defibrillator pads if there is any concern for development of ventricular dysrhythmias. The prognostic value of end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring in cardiac arrest secondary to accidental hypothermia has not been studied.

Adjunctive Testing

Once the diagnosis of hypothermia is confirmed by core temperature measurement, additional testing should include basic laboratory studies, toxicology screen, ECG, and chest radiograph (CXR). Typical laboratory findings are listed in Table 9.4. Slowed cardiac conduction manifests as a variety of ECG changes, the most common of which is the Osborne wave (Fig. 9.2), seen in approximately 80 % of hypothermic patients [7]. Baseline CXR is recommended due to the inherent risk of aspiration pneumonia in this patient population. CT head imaging in all hypothermic patients is not clearly indicated but should be considered if altered mental status is present despite temperature >32 °C or signs of head trauma are present [1]. Further workup should be pursued on an individual basis if associated trauma, infection, or other medical condition is suspected.

Table 9.4

Common laboratory derangements in hypothermia

Test | Typical result | Comments |

|---|---|---|

Hematocrit | High | Due to hemoconcentration from cold dieresis |

Potassium | High | |

Creatinine | High | |

Creatine kinase | High | Should be checked routinely as time down often unknown |

PT/PTT | High | Due to coagulation cascade enzyme denaturation at colder temperature; reported values may be normal as blood heated prior to testing |

Arterial blood gas | Variable | Recommend using uncorrected values [1] |

Lactate | High |

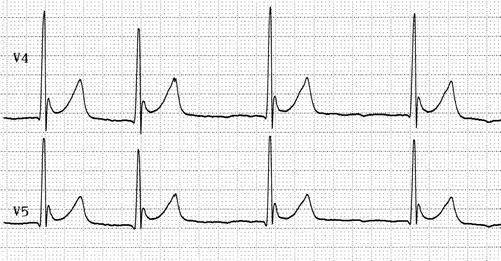

Fig. 9.2

Osborne wave. Osborne wave, or J wave, is frequently seen in hypothermia, although it is not pathognomonic for the condition. It is characterized by a positive deflection at the J point (negative in aVR and V1) and is usually seen best in the precordial leads. The height of the J wave generally corresponds to the degree of hypothermia [7] (Image courtesy of lifeinthefastlane.com)

Rewarming

There are four general approaches to rewarming: passive, active external, active internal, and extracorporeal [8]. The best method depends on the severity of hypothermia and resources available to the provider, although there are no randomized, controlled trials regarding treatment approach. The average rates of rewarming for each method are listed in Table 9.5.

Table 9.5

Rewarming techniques

Technique | Rate (°C/h) |

|---|---|

Removal of wet clothing, insulation | 0.5 |

Warm environment, warm oral fluids, active movement | 2 |

Forced-air heating device, warm IV fluids | 0.1–3.4 |

Peritoneal dialysis | 1–3 |

Hemodialysis | 2–4 |

Thoracic lavage | 3 |

Venovenous ECMO | 4 |

Venoarterial ECMO | 6 |

Cardiopulmonary bypass | 9 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree