INTRODUCTION

Abnormal uterine bleeding is an overarching term that is defined as bleeding from the uterine corpus that is irregular in volume, frequency, or duration in absence of pregnancy (Table 96-1).1 Vaginal bleeding is a common complaint in the ED, and differential diagnoses include pregnancy, structural abnormalities (e.g., polyps, fibroids), endometritis, coagulopathies, trauma, and various other causes. The prevalence of abnormal bleeding is estimated at 9% to 14% in the general population. Although vaginal bleeding may present as an acute or chronic problem, this chapter will focus on the ED evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding.

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | Bleeding that is abnormal in regularity, volume, frequency, or duration. Bleeding may be acute or chronic and is present for at least 6 months. |

| Heavy menstrual bleeding (heavy uterine bleeding [HUB] replaces menorrhagia) | Excessive menstrual bleeding that interferes with a woman’s physical, emotional, social, and quality of life. Note that the definition is menstrual bleeding deemed excessive by the patient regardless of duration, frequency, or timing. |

| Amenorrhea | Bleeding that is absent for >6 months. |

| Prolonged menstrual bleeding | Menstrual bleeding that is absent for >6 months. |

| Intermenstrual bleeding (replaces metrorrhagia) | Bleeding episodes between normally timed menstrual periods. |

| Irregular menstrual bleeding | Unpredictable onset of menses, with cycle variations >20 days over a period of 1 year. |

| Postmenopausal bleeding | Any bleeding that occurs >12 months after cessation of menstruation. |

MENSTRUAL CYCLE

In North America, average age of menarche is 12.5 years of age, approximately 2 years after the development of thelarche (breast budding). Early cycles are often anovulatory and irregular due to the immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Regular ovulatory cycles develop on average 2 years after the start of menarche.

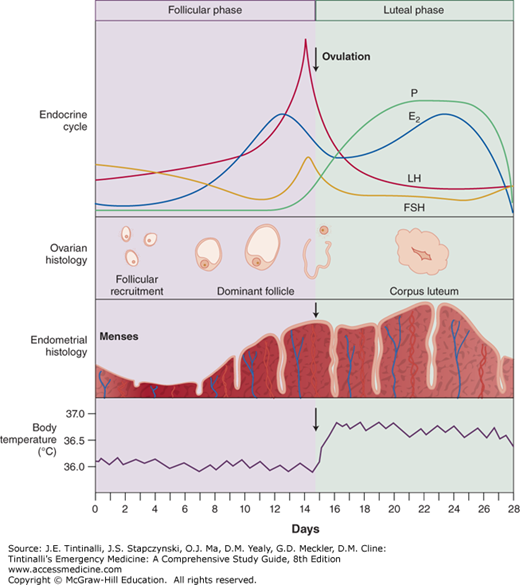

The normal menstrual cycle is 28 days and is divided into four phases: menses, follicular, ovulation, and luteal or secretory. Figure 96-1 depicts hormonal and endometrial changes associated with a normal menstrual cycle.

FIGURE 96-1.

The hormonal, ovarian, endometrial, and basal body temperature changes and relationships throughout the normal menstrual cycle. E2 = prostaglandin E2; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; LH = luteinizing hormone; P = progesterone. [Reproduced with permission from Patel DR, Greydanus DE, Baker RJ: Pediatric Practice Sports Medicine. © 2009, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.]

In response to the rising estrogen levels, the pituitary gland secretes follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, which stimulates the release of the mature oocyte. The residual follicular capsule forms the corpus luteum. During the luteal phase, the corpus luteum secretes estrogen and progesterone, which maintains the integrity of the endometrium and makes it more receptive to implantation. If fertilization and implantation occur, the developing embryo secretes human chorionic gonadotropin into the bloodstream, signaling the corpus luteum to continue the production of progesterone and estrogen necessary to support early pregnancy. In the absence of human chorionic gonadotropin, the corpus luteum involutes, and estrogen and progesterone levels fall. Hormonal withdrawal causes vasoconstriction in the spiral arterioles of the endometrium. As a consequence, the ischemic endometrial lining becomes necrotic and sloughs, which leads to menses. The vaginal effluvium contains blood, endometrial tissue, and fluid. The average amount of menstrual blood loss ranges from 25 to 60 mL.

The average tampon or pad absorbs 20 to 30 mL of vaginal effluent. However, judging the amount of blood loss by usage may be unreliable because personal habits vary greatly among women. In women with heavy bleeding, there may be insufficient time for fibrinolysis, so blood clots form.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Obtaining a focused medical history should include details of current bleeding episode, associated symptoms, and past medical history including reproductive and sexual history (Table 96-2). Pregnancy-related bleeding should always be considered and ruled out in reproductive-age patients. Patients may describe heavy bleeding as soaking of more than one pad or tampon within 1 hour or passing large clots. Up to 20% of women with heavy uterine bleeding have an underlying coagulation disorder, with von Willebrand’s disease being the most common. Screening for history of heavy menstrual bleeding since menarche, postpartum hemorrhage, surgery- or dental-related bleeding, and family history may help guide further evaluation for bleeding disorders. It is also important to ask about oral contraceptive use because missed doses are a frequent cause of bleeding. Questions about drug interactions and smoking are also important in determining the cause of bleeding.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Reproductive history | Age of menarche Menstrual history Date of the last menstrual period Pattern of normal and abnormal bleeding or discharge Presence of dysmenorrhea |

| Sexual history | Current sexual activity Contraception Use of barrier protection Pregnant—yes/no? Gravida and para Previous abortion or recent termination History of ectopic pregnancy History of pelvic inflammatory disease, sexually transmitted diseases, human immunodeficiency virus, and hepatitis status |

| History of trauma | — |

| Possibility of retained foreign body | — |

| Medications, including alternative and complementary medicine | — |

| Past medical history | Signs and symptoms of coagulopathy, including nosebleeds, petechiae, and ecchymoses Endocrine disorders, including diabetes, pituitary tumors, polycystic ovary disease, hyperthyroidism, and hypothyroidism Liver disease |

| Associated symptoms | Urinary, GI, musculoskeletal symptoms; fever or syncope |

To obtain an accurate sexual history from an adolescent patient, assure physician confidentiality and maintain a nonjudgmental attitude. If a female physician is requested, try to honor the request if at all possible. Always ask the parents for an opportunity to interview the patient without the parent present. Furthermore, all states allow minors to consent to diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases and drug abuse without parental consent.

The initial assessment includes evaluation of vital signs and hemodynamic status. However, significant signs of volume depletion may not be present until bleeding is profuse. Perform a focused physical examination including pelvic (speculum and bimanual) and abdominal exam to determine the cause of bleeding and to exclude life-threatening blood loss requiring emergent surgical intervention. Look for signs of other illnesses, including hyper- and hypothyroidism, galactorrhea, obesity associated with hirsutism, and liver disease. Petechiae, purpura, and mucosal bleeding require hematologic investigation.

For pelvic examinations in the ED, both male and female physicians are equally advised to have a chaperone present. Decisions regarding parent or guardian presence during examination of adolescents depend on the patient’s age and maturity level. Inspect the perineum, vulva, urethra, and perianal region before internal speculum exam. Evaluate the vaginal canal and cervix for lacerations, fissures, lesions, infection, tumors, and foreign bodies. On bimanual examination, determine the softness and patency of the cervical os, and ask about pain on cervical movement. Palpate the uterus and adnexa for size, consistency, tenderness, and masses.

In a virginal patient, a rectovaginal digital examination is generally sufficient. In the case of trauma, concern for sexual abuse, or vaginal foreign body, a vaginal examination is necessary. Adolescents with intact hymen can generally tolerate a speculum examination if a narrow Pederson-type adolescent or Huffman pediatric speculum is used. Conscious sedation or full anesthesia may be required, depending on the psychological response of the patient, the circumstances, and the extent of the injury or disease.

Several techniques may help facilitate performing a pelvic examination in elderly women, including using a smaller speculum with generous lubrication and proper positioning. Age, immobility, and degenerative joint disease may make it difficulty to place the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position. Patients may be positioned supine, with the head supported with a pillow, and with knees flexed and with hips externally rotated (frog-leg position). The pelvis may be elevated using padding or an upside-down bedpan. If vaginal bimanual examination cannot be performed due to vaginal atrophy, a recto-abdominal approach may be attempted. Abnormalities such as irregular nodules, masses, or thickened rectovaginal septum may suggest malignancy.

CAUSES OF VAGINAL BLEEDING

The causes of abnormal vaginal or uterine bleeding in nonpregnant females are classified into structural and nonstructural causes, using the acronym: PALM-COEIN: Polyp, Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, Malignancy and hyperplasia, Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial, Iatrogenic, and Not otherwise classified.2 Causes of bleeding based on age are shown in Table 96-3. The term abnormal uterine bleeding encompasses all causes of abnormal bleeding in nonpregnant women, and the most likely causes are largely determined by patient age. Because the first clinical signs of heavy menstrual bleeding (heavy uterine bleeding) are noted after the onset of menses during early adolescence, structural causes are uncommon. Anovulatory and bleeding disorders are most common during this time period (ages 13 to 19). Pregnancy-related complications become the most common cause of abnormal vaginal bleeding during the reproductive years. Issues regarding pregnancy are covered in chapters 98, “Ectopic Pregnancy and Emergencies in the First 20 Weeks of Pregnancy” and 100, “Maternal Emergencies after 20 Weeks of Pregnancy and in the Postpartum Period.”

| Adolescent | Reproductive | Perimenopausal | Postmenopausal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anovulation (hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian immaturity) | Pregnancy | Anovulation | Atrophic vaginitis (30%) |

| Pregnancy | Anovulation (PCOS) | Uterine leiomyomas | Exogenous hormone use (30%) |

| Exogenous hormones or OCP | Exogenous hormone use or OCP | Cervical and endometrial polyps | Endometrial lesions, including cancer (30%) |

| Coagulopathy | Uterine leiomyomas | Thyroid dysfunction | Other tumor—vulvar, vaginal, cervical (10%) |

| Pelvic infections | Cervical and endometrial polyps | ||

| Thyroid dysfunction |

Abnormal uterine bleeding as a result of local structural pathology such as polyps and fibroids is not typically seen until women reach their mid 30s. Perimenopausal anovulatory bleeding is typically seen in the mid to late 40s. Postmenopausal bleeding is often related to atrophic vaginitis, exogenous hormones, and malignancy. A summary of the causes by age is provided in Table 96-3.

STRUCTURAL CAUSES OF VAGINAL BLEEDING

Endometrial and endocervical polyps are epithelial proliferations that most often are benign. Although most polyps are asymptomatic, polyps can be a cause of abnormal uterine bleeding in women older than 35 years. A common symptom is intermenstrual bleeding, and diagnosis is made on hysteroscopy.

Adenomyosis is the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium. The histopathology is often diffuse within the uterus, but localized areas of growth are called adenomyomas. Symptoms include painful, heavy periods most commonly seen in the fourth and fifth decade of life. ED management is aimed at symptomatic treatment, analgesics, and evaluation for anemia. Leuprolide acetate (Lupron), a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog plus add-back therapy, or a levonorgestrel intrauterine device (Mirena) for 6 months may be initiated as an oupatient.3 MRI is the imaging modality of choice, but US is a good alternative. Patients with severe bleeding unresponsive to medical management often require surgical management.

Uterine fibroids (also called leiomyoma or myoma) are the most common benign tumors of the pelvis in women; an estimated 25% of white women and 50% of black women have fibroids in their reproductive years. This number increases with age. The cause is unclear, but fibroid growth is dependent on genetic factors and hormones: gonadotropin-releasing hormone, estrogen, and progestin. Leiomyomas decrease in size during menopause. In some cases, fibroids will enlarge early in pregnancy and with oral contraceptive pill use. Most fibroids are asymptomatic, but up to 30% of patients with leiomyomas experience pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Acute pain is rare, but severe pain may be experienced with torsion or degeneration. Degeneration results from rapid growth and loss of blood supply, often seen during early pregnancy. A rare case of spontaneous fibroid rupture causing massive intra-abdominal hemorrhage has been reported in the literature.4

Signs and symptoms of fibroids vary depending on fibroid size and location. Large fibroids may be palpated on abdominal or rectal exam. Symptoms of acute degeneration include tenderness, rebound guarding, fever, and elevated WBC count. Pedunculated subserosal leiomyomas may undergo torsion or cause uterine cramping. Rapid growth at any age or growth after menopause is highly suspicious for malignant transformation. The best diagnostic test is ultrasonography and is as sensitive as MRI.

The management of uterine fibroids depends on the severity and duration of symptoms. In the ED, management is focused on treating complications associated with fibroids. Iron deficiency anemia is often long-standing and may require a blood transfusion. Other complications are rarer, but constipation, urinary retention, vaginal or intraperitoneal hemorrhage, deep vein thrombosis, and mesenteric thrombosis have been reported.5 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the mainstays for analgesia in the ED. Medical management with hormonal agents may be initiated in the ED with gynecologic consultation. Intrauterine fibroids are treated surgically with hysteroscopy. Surgical removal is associated with a 25% to 30% rate of recurrence and significant bleeding complications. Uterine artery embolization is an effective treatment for symptomatic fibroids, resulting in decreased fibroid volume and alleviation of symptoms.6,7,8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree