ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

RICHARD A. SALADINO, MD AND DENNIS P. LUND, MD

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

Trauma is the most common cause of death in children between 1 and 18 years of age in the United States; more than 10,000 children die each year from injuries. Blunt trauma accounts for more than 90% of childhood injuries; the most common associated mechanisms are falls and motor vehicle–related trauma. Although injury to the abdomen accounts for only 10% of injuries in children with trauma, it is the most common unrecognized cause of fatal injuries. Therefore, a compulsive and systematic approach to timely identification and treatment of abdominal injuries is required.

KEY POINTS

Children are at greater risk than adults for intra-abdominal injuries after blunt trauma because of their immature musculoskeletal system.

Children are at greater risk than adults for intra-abdominal injuries after blunt trauma because of their immature musculoskeletal system.

The overlying muscles and associated skeleton are more pliable than in adults and, therefore, less protective; children have a higher abdominal organ-to-body mass ratio.

The overlying muscles and associated skeleton are more pliable than in adults and, therefore, less protective; children have a higher abdominal organ-to-body mass ratio.

A given force delivered to the abdomen is distributed over a smaller body surface area, increasing the likelihood of injury to the underlying structures.

A given force delivered to the abdomen is distributed over a smaller body surface area, increasing the likelihood of injury to the underlying structures.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Signs and Symptoms

• Abdominal Distension: Chapter 7

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

• Genitourinary Trauma: Chapter 116

• Musculoskeletal Trauma: Chapter 119

• Thoracic Trauma: Chapter 123

Procedures and Appendices

THE APPROACH TO THE PEDIATRIC PATIENT WITH ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Priorities in evaluation and treatment of any child with trauma include recognition and relief of airway obstruction, appropriate protection of the cervical spine, and management of life-threatening chest injuries and shock.

• Once resuscitation and cervical spine stabilization have begun, evaluation of the abdomen is included in both the primary and secondary surveys.

• Occult abdominal trauma occurs in many settings, including children restrained only by a lap belt and in child abuse. Index of suspicion must be high in these cases.

Current Evidence

Blunt injuries account for most of the morbidity and mortality of childhood trauma, although the frequency with which penetrating injuries occur is increasing.

Goals of Treatment

The primary objective of treatment is to determine the presence or absence of intra-abdominal injury. The evaluation for intra-abdominal injuries in children starts with a determination of the mechanism of trauma, elicited from witnesses, caregivers, and emergency medical personnel. Penetrating trauma is usually evident on careful inspection of both the anterior and posterior torsi. In contrast, blunt abdominal trauma must be suspected from both historical information and careful physical examination. Children with severe multiple trauma are obviously at risk for intra-abdominal injuries, but sufficient energy to injure may also be present in apparently minor falls, direct blows to the abdomen from balls, bats, bicycle handlebars, and countless toys, and during contact sports.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

Life-threatening abdominal injuries may be occult or manifest in several ways: abdominal ecchymoses or distention, shock, or external hemorrhage (e.g., from a penetrating injury). Historical information or physical examination findings are often subtle or lacking. Children have the capacity to maintain a normal blood pressure level in the face of significant blood loss and hence may mask major intra-abdominal bleeding. The examining physician must always keep in mind that the abdomen is a large potential reservoir for blood loss.

Triage Considerations

The American College of Surgeons suggests that triage of the trauma patient be based upon severity of the mechanism of injury and physiologic status of the patient. Clearly the patient with a mechanism associated with high velocity or with abnormal vital signs must be immediately resuscitated and evaluated for injuries. That said, even those patients with a lesser mechanism of injury and stable vital signs should be evaluated with great vigilance.

Clinical Assessment

Physical examination. A traumatized child is often difficult to examine; pain associated with extra-abdominal injuries may obscure abdominal findings. In addition, the results of physical examination may be subtle or unreliable in an unconscious, intoxicated, agitated, or fearful child. Vital signs, including blood pressure and pulse, may be normal for age, especially in children with isolated injuries of the liver and spleen. Furthermore, external signs of injury, abdominal tenderness, and absent bowel sounds seldom differentiate pediatric patients who require laparotomy from those who do not.

Careful serial examinations are critically important in maintaining the index of suspicion necessary to proceed with more sophisticated testing when appropriate. Inspection should note abrasions, lacerations, ecchymoses, penetrating wounds (including missile entry and exit sites), and telltale markings (e.g., seat belt marks, tire tracks). Attention should be paid to the anterior and posterior abdomen and to both flanks, as well as to the lower thorax, when considering abdominal injuries. Abdominal distention may be caused by hemoperitoneum or peritonitis but most often results from gastric distention from air swallowed by the crying child. Early gastric decompression may assist the abdominal examination and prevent vomiting with aspiration of gastric contents. The presence or absence of bowel sounds is generally not of much significance in the initial evaluation, but prolonged ileus may be a sign of intra-abdominal pathology. Tenderness upon palpation, percussion, or shaking may be caused by abdominal wall contusion or may indicate intra-abdominal injuries. Pelvic stability is evaluated by gently compressing and distracting the iliac wings.

Digital rectal examination should be performed; the presence of blood may indicate perforation of the bowel. A boggy or high-riding prostate, blood at the urethral meatus, or a distended bladder may be present with urethral disruption and preclude bladder catheterization until a retrograde urethrogram has been performed (see Chapter 116 Genitourinary Trauma). Diminished or absent rectal sphincter tone may indicate a spinal cord injury.

Laboratory assessment: Blood should be obtained and sent for immediate baseline hemoglobin measurement and typing and cross-matching, not only in all instances of multiple trauma but also if isolated intra-abdominal injury is suspected.

Routine multipanel laboratory testing (so-called “trauma panels”) historically has been standard for patients with trauma, but more recent studies have called into question this undifferentiated approach. Nonetheless, laboratory studies that are commonly added include measurement of liver transaminases, amylase, lipase, and urinalysis.

Many recent studies indicate that, in combination with the presence of physical examination findings, abnormal laboratory findings contribute to the identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries. Elevated serum liver transaminase levels may be associated with intra-abdominal trauma, especially hepatic injuries. Screening for intra-abdominal injuries by evaluating transaminase levels is not universally accepted because sensitivity and specificity vary widely in the literature, but some data suggest that elevated transaminase levels (aspartate aminotransferase more than 200 U per L and alanine aminotransferase more than 125 U per L) correlate well with hepatic injuries. Using thresholds such as these may allow for more judicious use of computerized tomographic (CT) scan of the abdomen for children with blunt abdominal trauma.

Examination of the urine may also play a role in an increased suspicion for intra-abdominal injury after blunt force trauma to the abdomen. Grossly bloody urine indicates likely injury to the kidneys and has been shown to be associated with nonrenal intra-abdominal injuries in pediatric patients with trauma. The predictive capacity of microscopic hematuria is controversial. In one study, microscopic examination of urine that revealed more than 50 red blood cells (RBCs) per high-powered field (hpf) was 100% sensitive and 64% specific for the presence of an intra-abdominal injury (see Chapter 116 Genitourinary Trauma). A more recent study suggests consideration of CT scan of the abdomen in the context of a urinalysis demonstrating as few as five or more RBCs per hpf when the history indicates a significant force has been applied to the abdomen. In addition, clinicians must remember that major trauma may cause complete disruption of a renal pedicle without any hematuria.

Management

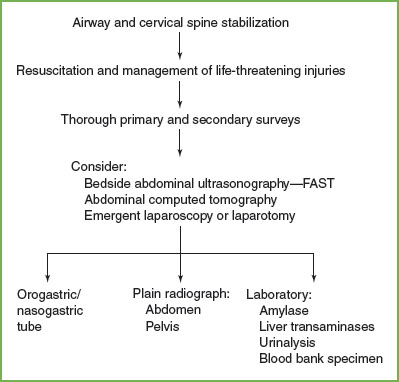

Basic principles of management. Airway management and cervical spine stabilization are first priorities (Fig. 111.1). Supplemental oxygen should be administered to any child with significant injuries, regardless of whether obvious signs of shock are present. Intravenous or intraosseous access should be obtained while the primary survey is completed. Immediate life-threatening injuries should be treated promptly. Hemorrhagic shock should be addressed with rapid infusion of isotonic crystalloid solution. A first intravenous administration of a bolus of 20 mL per kg may be given rapidly, followed by a second bolus of 20 mL per kg, if the pulse and blood pressure remain outside the physiologic range. If hemodynamic instability persists after 40 mL per kg of crystalloid, ongoing bleeding should be suspected and administration of blood strongly considered. The blood bank at a trauma center not only should be able to provide type-specific blood in a short time frame but must also have O-negative packed RBCs ready for resuscitation if needed. Large-bore catheters are preferable, whether in the upper or lower extremities, to allow rapid infusion of large volumes of fluid during resuscitation. Accessing the femoral vein is acceptable and in fact is a preferred site in children when central access is needed.

FIGURE 111.1 Initial evaluation and treatment of the child with abdominal trauma. FAST, focused abdominal sonography for trauma.

The American College of Surgeons currently recommends that aggressive fluid resuscitation be pursued. Although there is some suggestion that less rigorous (hypotensive) fluid resuscitation may improve survival by limiting hemorrhage into the peritoneal space, pursuing this strategy in the management of children is still controversial and not part of the approach to the injured child with hypotension.

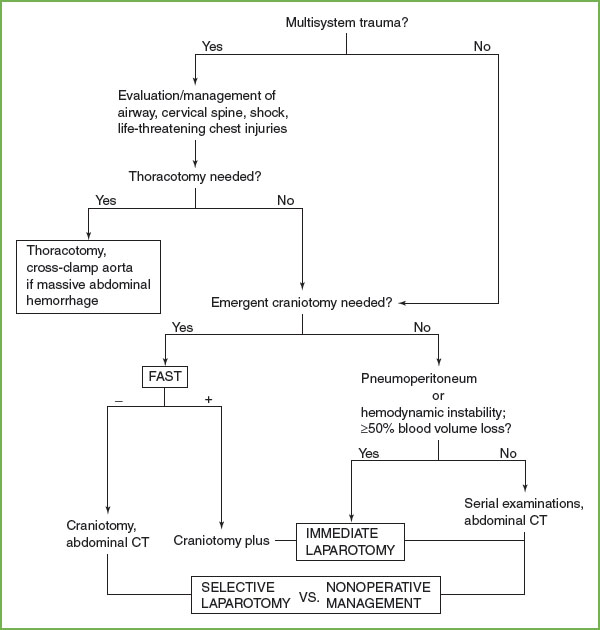

As the initial evaluation proceeds, the priorities of management depend on the extent of multisystem injuries and the condition of the patient (Fig. 111.2). Patients who are unstable as a result of ongoing blood loss or an expanding intracranial hemorrhage require operative intervention early in the evaluation phase.

Initial management of the unstable patient. Immediate life-threatening injuries, such as airway obstruction, tension pneumothorax, pericardial tamponade, and obvious sources of external blood loss, must be treated promptly upon detection.

If significant head trauma has occurred, a determination must be made regarding the need for immediate neurosurgical intervention. A rapidly performed CT scan of the head is usually sufficient to determine the presence of a hematoma, and the findings will dictate the next steps with regard to evaluation of the abdomen. If hemodynamic instability or the need for immediate craniotomy exists and does not allow for CT evaluation of the abdomen (Fig. 111.2), a focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST examination) should be performed either in the ED or in the operating suite. In the presence of a positive FAST examination, laparotomy or laparoscopy and craniotomy proceed simultaneously. Finally, if neither thoracotomy nor craniotomy is indicated, emergent laparotomy or laparoscopy is performed when pneumoperitoneum is noted on a plain radiograph or when the patient remains hemodynamically unstable in the face of historical or physical evidence of abdominal trauma. With massive hemorrhage, fresh frozen plasma and platelets should be administered along with packed RBCs.

FIGURE 111.2 Management of blunt abdominal trauma. FAST, focused abdominal sonography for trauma; CT, computed tomography (Table 111.2).

TABLE 111.1

INDICATIONS FOR ABDOMINAL COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHIC SCAN IN PEDIATRIC TRAUMA PATIENTS

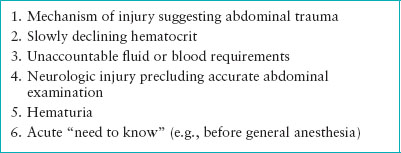

Initial management of the stable patient. Commonly, the injured child can be stabilized in the ED with proper airway and cervical spine management, and with intravenous fluid therapy and blood transfusion. A careful secondary survey should then be performed. On the basis of history and careful, serial abdominal examinations, CT is indicated when intra-abdominal injuries are suspected (Table 111.1). An abdominal CT scan may be merited based solely on severe force inherent in a particular mechanism of injury, despite an unremarkable physical examination or the absence of abnormal screening laboratory values.

Additional management. Children with abdominal trauma often need decompression of the stomach; this procedure facilitates examination, may provide information concerning gastric or diaphragmatic injury (bloody aspirate, radiographic evidence of the nasogastric tube in the thoracic cavity), and relieves the discomfort of an ileus. Major maxillofacial trauma precludes nasogastric tube placement, but an orogastric tube suffices in these instances. Urinary bladder catheterization may provide evidence of genitourinary system injury and is helpful in monitoring urinary output. Bladder catheterization is contraindicated when urethral disruption is suspected on the basis of the findings described previously.

FOCUSED ABDOMINAL SONOGRAPHY FOR TRAUMA

Goals of Treatment

FAST is typically performed in the ED during the secondary survey. The operator looks at four windows in the abdomen: the left upper quadrant, the right upper quadrant, the pericardium via a subxiphoid window, and the pelvis. The purpose of the scan is to detect free fluid. Free fluid in any of these areas indicates the need for further evaluation and treatment.

The utility of FAST in the management of pediatric patients remains controversial. The literature for pediatric patients with intra-abdominal injuries suggests that FAST is not sufficiently sensitive and CT scanning remains the gold standard for the radiologic evaluation in children. Nonetheless, there is a role for FAST in pediatric populations, particularly in unstable children or children who need immediate transfer to the operating suite for an emergent procedure, such as cranial decompression. Although a negative FAST finding does not exclude injury, a positive FAST finding is evidence enough to warrant exploration of the abdomen, either with laparoscopy or with laparotomy, in such a patient (see Chapter 142 Ultrasound).

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

•

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree