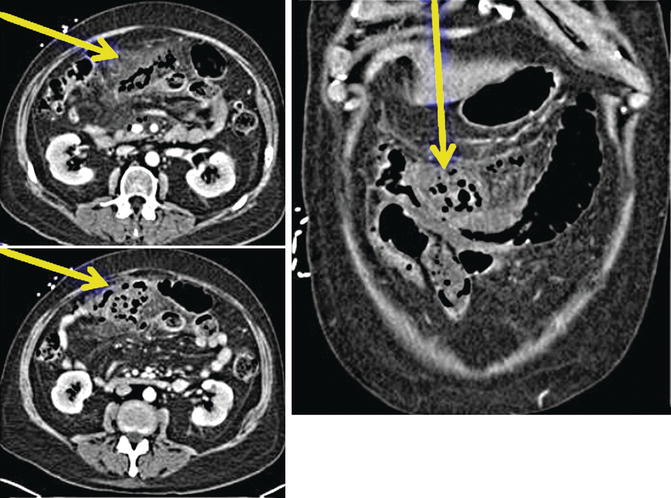

Fig. 79.1

Perforated diverticulitis in the transverse colon

Question

How should this patient’s intraabdominal condition be managed?

Answer

This patient has an intraabdominal infection from a perforated transverse colon, as demonstrated by his physical exam findings, laboratory values and cross-sectional imaging. The patient should receive early goal-directed resuscitation based on the Surviving Sepsis Guidelines in the emergency room or the ICU [1]. Broad spectrum antibiotics to cover gram negative Enterobacteriaceae and enteric anaerobes should be initiated. He should be taken to the operating room expeditiously for exploratory laparotomy while undergoing ongoing resuscitation.

Principles of Management

Diagnosis

Intraabdominal infections should be suspected in patients with evidence of gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain. They may or may not have signs of inflammation including fever, tachycardia or tachypnea [2]. A history including recent abdominal operations may help identify the source of the intraabdominal infection. Physical exam is important but may be nonspecific in patients that are obtunded, intubated, sedated, elderly or on immunosuppressive therapy [2, 3]. Patients presenting with signs of peritonitis including abdominal rigidity, guarding and rebound tenderness should be considered for urgent laparotomy [4].

Basic laboratory tests including complete blood count, and electrolytes should be obtained. If a hepatobiliary or pancreatic source is suspected, liver enzymes and an amylase and lipase can be added [5]. Additional labs including those measuring end organ perfusion such as lactate and mixed venous oxygen saturation should be obtained if the patient is suspected of having severe sepsis or septic shock [1]. Further imaging studies should be obtained in patients with suspected intraabdominal infection, if feasible. Cross-sectional imaging with computed tomography (CT scan, Fig. 79.2) with intravenous contrast is the diagnostic modality of choice for most cases of intraabdominal infection such as appendicitis, diverticulitis and colitis. Enteral contrast is useful to differentiate the viscera for potentially pathologic fluid collections such as abscesses or anastomotic leaks. However, the utility of enteral contrast in the emergency situation is somewhat debatable, and should be utilized according to local protocols. Intravenous contrast permits optimal visualization of infectious processes, inflammation, ischemia, hemorrhage and solid organ assessment [3]. If a biliary source is suspected, ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality [6].

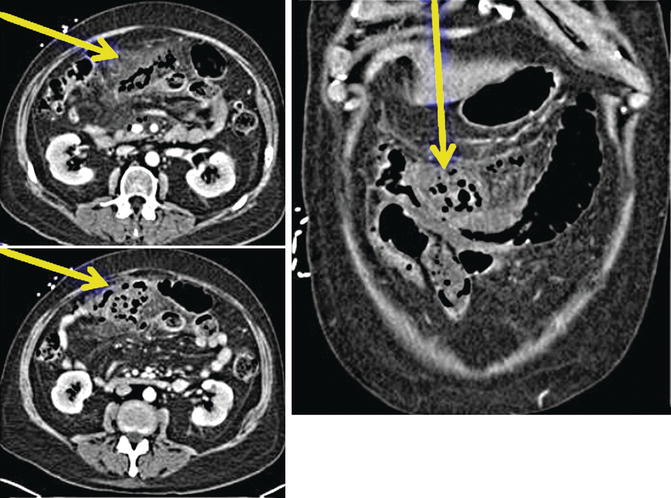

Fig. 79.2

CT scan imaging demonstrating inflammatory changes around the mid-transverse colon with extraluminal air and fluid in this area, consistent with a perforation of the transverse colon and peritonitis

Resuscitation

Patients with intraabdominal infections become volume depleted by several mechanisms including decreased oral intake, increased sensible losses due to vomiting and diarrhea and increased insensible losses due to third spacing, fever and tachypnea [7]. Fluid resuscitation should begin as soon as a diagnosis of sepsis is suspected, following the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines [1, 2, 7].

To Be Completed Within 3 h of Time of Presentation1

- 1.

Measure lactate level

- 2.

Obtain blood cultures prior to administration of antibiotics

- 3.

Administer broad spectrum antibiotics

- 4.

Administer 30 ml/kg crystalloid for hypotension or lactate ≥4 mmol/L

To Be Completed Within 6 h of Time of Presentation

- 5.

Apply vasopressors (for hypotension that does not respond to initial fluid resuscitation) to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥65 mmHg

- 6.

In the event of persistent hypotension after initial fluid administration (MAP < 65 mmHg) or if initial lactate was ≥4 mmol/L, re-assess volume status and tissue perfusion with either

Repeat focused exam (after initial fluid resuscitation) including vital signs, cardiopulmonary, capillary refill, pulse, and skin findings

Or two of the following:

Measure CVP

Measure ScvO2

Bedside cardiovascular ultrasound

Dynamic assessment of fluid responsiveness with passive leg raise or fluid challenge

- 7.

Re-measure lactate if initial lactate elevated.

In patients with severe infections and ongoing contamination, resuscitation may not be successful until source control is achieved, and a necessary source control procedure should not be unduly delayed in an effort to achieve all goals of resuscitation. However, resuscitation efforts should continue intraoperatively and postoperatively in such patients.

Source Control

Source control is one of the fundamental treatment strategies for intraabdominal sepsis. The goal is to remove the infected fluid, debride infected solid tissue, remove infected devices or foreign bodies and gain control of ongoing enteric drainage by correcting anatomic derangements [8]. It may be obtained by either operative intervention or percutaneous drainage, depending on size and location of the infection and acuity of the patient [4].

Operative intervention, either open or laparoscopic, should be performed in patients with peritonitis, suspected bowel ischemia or necrosis, evidence of uncontrolled, on-going contamination or those who have failed percutaneous drainage [2, 4, 7, 9]. In unstable patients, damage control surgery may be performed. This concept has been adopted from its use in trauma patients. It is a multistep process, with the first stage being evacuation of infected material and control of gross contamination, including wide drainage [2, 7, 10, 11]. The abdomen is temporarily closed and the patient then undergoes further resuscitation to restore more normal physiologic functions. Once resuscitation is complete, re-laparotomy for definitive source control and reconstruction can be performed. If the patient’s condition worsens during this resuscitative phase, earlier relaparotomy should be considered. The abdomen can be definitively closed once there are no concerns for ongoing ischemia, necrosis or infection [7].

Although planned re-laparotomy benefits some patients with severe peritonitis, its use should be restricted to patients who are physiologically unstable, are at risk for development of an abdominal compartment syndrome with early fascial closure, have a concern for ongoing bowel ischemia, or who will need further source control procedures to gain adequate control of the infection. The routine use of planned re-laparotomy for all patients with severe secondary peritonitis was not shown to be beneficial in a prospective randomized controlled trial [12]. Rather, on-demand re-laparotomy, employed in just those patients who manifested signs of ongoing infection, was found to be associated with shorter ICU and hospital lengths of stay and reduced expenses compared to planned re-laparotomy in all patients.

Percutaneous drainage is often the initial treatment for intraabdominal abscesses, as it as effective as surgical drainage and is less invasive, with resultant lower morbidity and mortality rates [2, 7, 13, 14]. It is also useful for patients who are poor surgical candidates [7]. It is also possible that it can serve as a temporizing measure in severely-ill patients, such as those with infected pancreatic necrosis.

Anti-Infective Therapy

Antimicrobial therapy should be started within one hour in patients with septic shock due to complicated intra-abdominal infections, and as soon as feasible in other patients who do not have evidence of hemodynamic or organ compromise [1, 2]. Therapy should be selected according to the whether or not the patient as a community-acquired or a health-care-associated infection (Tables 79.1 and 79.2). It should also be based on local microbiologic data.

Table 79.1

Agents and regimens that may be used for the initial empiric treatment of extra-biliary complicated intra-abdominal infection (community-acquired infection in adults)

Regimen

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|