ABDOMINAL EMERGENCIES

RICHARD G. BACHUR, MD

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

Pediatric abdominal complaints are common, and ED physicians are challenged to distinguish common, innocent gastrointestinal complaints from surgical emergencies. Logical diagnostic strategies and prompt recognition of surgical emergencies should be the goal of the evaluation. For abdominal surgical emergencies, the clinical evaluation should focus on timely recognition of a surgical condition and early involvement of a surgeon. Ideal care would limit complications such as peritonitis and ischemic bowel.

KEY POINTS

Bilious emesis in a young infant is a surgical emergency

Bilious emesis in a young infant is a surgical emergency

Young children with appendicitis often have atypical presentations

Young children with appendicitis often have atypical presentations

Intussusception can present with profound altered mental status

Intussusception can present with profound altered mental status

Bloody stool or blood per rectum may represent ischemic bowel

Bloody stool or blood per rectum may represent ischemic bowel

RELATED CHAPTERS

Signs and Symptoms

• Abdominal Distension: Chapter 7

• Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Chapter 28

Clinical Pathways

• Abdominal Pain in Postpubertal Girls: Chapter 82

• Appendicitis (Suspected): Chapter 83

Medical, Surgical, Trauma

• Gastrointestinal Emergencies: Chapter 99

• Gynecology Emergencies: Chapter 100

ACUTE NONPERFORATED APPENDICITIS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Young children often have nonclassic presentations of appendicitis

• Pain and tenderness will vary based on exact location of the appendix

• Rapid improvement in pain in a child with high suspicion of appendicitis may occur at the time of perforation

• Equivocal ultrasounds for appendicitis should not lead to a CT if suspicion is relatively low

Current Evidence

Acute appendicitis is the most common, nontraumatic surgical emergency in children. Anatomic characteristics may influence the incidence and presentation of appendicitis throughout childhood. Lymphoid hyperplasia within the appendix is maximal in adolescence and might be related to the peak incidence in this age group. Generally, obstruction of the appendix (by fecal material, an appendicolith, or simply lymphoid hyperplasia) is believed to be a key step in the development of appendicitis. Once obstructed, bacterial overgrowth and invasion into the mucosal barrier leads to progressive inflammation and dilation. Localized pain and tenderness develops. Perforation rarely develops before 12 hours of pain but is common after 72 hours. Perforation can lead to generalized peritonitis or focal abscesses. Since younger children have a relatively underdeveloped omentum, they are much more likely to present with diffuse peritonitis.

Goals of Treatment

Early recognition and surgical excision prior to perforation is ideal. The clinical team should consider advanced diagnostic imaging for children without typical presentations or examination findings. Clinical outcomes for patients with suspected appendicitis include accurate identification of appendicitis over medical etiologies of focal abdominal tenderness, limiting the use of computed tomography among patients with uncomplicated acute appendicitis, minimizing the number of negative appendectomies, operative care prior to perforation, and the consideration of serial examinations over advanced imaging for patients considered low risk for appendicitis.

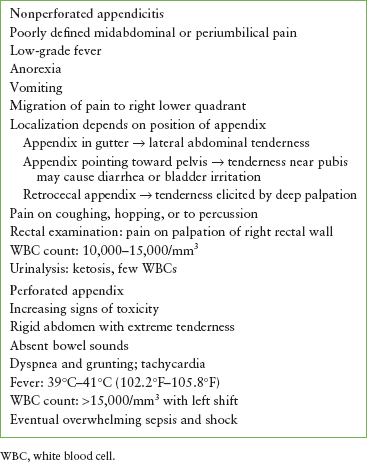

TABLE 124.1

PROGRESSION OF SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS OF APPENDICITIS

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

The peak incidence of appendicitis is 9 to 12 years of age. Although neonatal cases have been reported, appendicitis rarely occurs in children younger than 2 years of age. Predictably, the diagnosis is very difficult in children younger than 5 years of age. The emergency physician must accurately evaluate the child and promptly consult a surgeon when the diagnosis is clear or when appendicitis cannot be safely ruled out. Such consultation is especially urgent in younger children, in whom perforation can occur within 8 to 24 hours of the onset of symptoms. Usually the child with appendicitis initially complains of poorly defined and poorly localized midabdominal or periumbilical pain. Unfortunately, this symptom is common to many other intra-abdominal, nonsurgical problems. In the young and, to a lesser extent, the older child, vomiting and a low-grade fever often occur. Characteristically, the pain then migrates to the right lower quadrant (Table 124.1).

Triage Considerations

Children with abdominal pain and localized right lower quadrant tenderness or guarding should be evaluated promptly for appendicitis. Associated fever, extreme pain, and ill appearance may imply perforation and demand emergent treatment and surgical consultation. Shock related to peritonitis, sepsis, or severe dehydration is rare.

Clinical Assessment

Because the position of the appendix may vary in children, the localization of the pain and the tenderness on examination may also vary. An appendix that is located in the lateral gutter may produce flank pain and lateral abdominal tenderness; an inflamed appendix pointing toward the left lower quadrant may produce hypogastric tenderness and pain with urination (from bladder contraction). An inflamed low-lying, pelvic appendix may not cause pain at McBurney’s point, but instead may cause diarrhea from direct irritation of the sigmoid colon. Anorexia and nausea are common; vomiting is more common in younger children. In early stages, the patient may complain of pain with motion or walking and as peritoneal irritation worsens, the child will prefer to lay motionless in the bed.

When obtaining the history, the physician needs to consider other causes of abdominal pain, which may mimic appendicitis but, in fact, are nonsurgical (see Chapter 48 Pain: Abdomen). Concurrent GI illness in other family members or contacts suggests the possibility of an infectious gastroenteritis. Constipation, streptococcal pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, lower lobe pneumonia, mesenteric adenitis, and ovarian cyst are common conditions often masquerading as appendicitis. Although the presentation is generally more rapid and severe, torsion of the ovary and ectopic pregnancy should be considered in female patients with sudden onset of severe pain.

On examination, palpation is usually reliable in demonstrating focal tenderness at the site of the inflamed appendix. If the appendix is in the pelvis or retrocecal area, however, typical anterior peritoneal signs may be absent. When the inflamed appendix is not close to the anterior abdominal wall, as in the case of retrocecal appendix, tenderness may be more impressive on deep palpation of the abdomen or by palpating in the flank. Percussive tenderness, shake tenderness, pain with coughing or hopping suggests peritoneal irritation. Rovsing sign, pain in the right lower quadrant upon palpating the left lower quadrant, is difficult to assess in young children but when present is highly suggestive of appendicitis. A properly performed rectal examination can contribute to the clinical impression: the examining finger should be inserted as fully as possible without touching the area of presumed tenderness and then, when the child is relaxed and taking deep breaths, the examiner can indent an area high on the right rectal wall. A sudden involuntary reaction implies localized tenderness. In a child with a history of probable appendicitis for more than 2 or 3 days, a boggy, full mass may also be in this location, suggesting an abscess.

A CBC in a child with appendicitis usually shows an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count in the range of 10,000 to 15,000 per mm3 in the first 12 to 24 hours of the illness. As the appendix becomes more gangrenous, the WBC count rises further, and the differential demonstrates more neutrophils and an increasing number of bands. The WBC or absolute neutrophil count (ANC) is elevated in 92% of cases. At a threshold value of 10,000 per mm3 (WBC) or 6,700 per mm3 (ANC), the sensitivity is 96% but the specificity is 51%. C-reactive protein has limited value in the evaluation of nonperforated appendicitis but when used, it has improved sensitivity after 24 hours of symptoms. Urinalysis often shows ketosis. If the inflamed appendix lies over the ureter or adjacent to the bladder, low-grade pyuria may be present. An abdominal radiograph may show an appendicolith (8% to 10%), localized ileus with air–fluid levels, a gaseous loop in the right lower quadrant, or more commonly, a nonspecific bowel gas pattern. Subtle radiographic findings include a blurred psoas margins and thickened cecal wall. Rarely, pneumoperitoneum may be seen with perforated appendix.

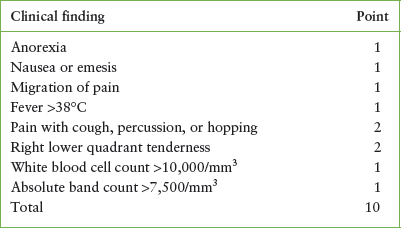

TABLE 124.2

PEDIATRIC APPENDICITIS SCORE

Several scoring systems have been offered to help differentiate appendicitis from other causes of abdominal pain in children. Most of the scoring systems have been adapted to assign risk classifications rather than determining the need for operative care. Many departments have modified the Pediatric Appendicitis Score or Alvarado Score to guide surgical consultation and advanced imaging. The Pediatric Appendicitis Score is shown in Table 124.2. Although exact score cut-offs are not defined consistently between guidelines, children with scores less than 3 are often considered low-risk, whereas 3 to 6 and >6 are considered intermediate and high-risk respectively. See Chapter 83 Appendicitis (Suspected) for the Evaluation of Patients with Suspected Appendicitis.

Management

If the clinical and laboratory findings of acute appendicitis are convincing, no further studies are indicated and a surgeon should be consulted. Significant pain should be treated with intravenous narcotics even before surgical evaluation. Patients with equivocal findings should be monitored with serial examinations or have radiologic studies to aid diagnosis. CT and US have both been used for diagnosis. US has a reported sensitivity of 80% to 92% with a specificity of 86% to 98%. Secondary signs of appendicitis on ultrasound (focal edema of fat, free fluid, local ileus) are helpful if the appendix is not visualized. Technically, a noncompressible enlarged appendix is diagnostic of appendicitis, although the study must be considered equivocal if the appendix is not identified. Focal CT has a diagnostic sensitivity of 95% with a specificity of 96%. CT can identify an enlarged appendix, focal thickening of the cecum, periappendiceal inflammation, mesenteric nodes, and fluid collections associated with perforation. Protocols using intravenous (IV) contrast plus rectal contrast or oral contrast vary by institution. In general, US has less utility in patients with a high body mass index, and CT is most interpretable in patients with adequate periappendiceal fat. US may be preferred in adolescent females as an initial study if gynecologic conditions are suspected such as ovarian cyst, tuboovarian abscess, ovarian torsion, or ectopic pregnancy (see Chapter 82 Abdominal Pain in Postpubertal Girls for the Evaluation of Lower Abdominal Pain in Post-pubertal Girls). The management of children with nondiagnostic ultrasounds should be guided by the level of clinical suspicion; for children with lower suspicion, serial examinations and observation are indicated over CT examination. MRI has recently been introduced as another option over CT, but data are lacking on performance.

At this time, nonperforated pediatric appendicitis is primarily managed surgically although there are ongoing trials of nonoperative treatment with antibiotics for selective cases of early, uncomplicated appendicitis. The preoperative preparation of a patient with acute appendicitis should include electrolytes if the patient has been vomiting or has had poor fluid intake for more than a few hours. IV fluids should be started with the goal of rapid intravascular expansion and then correction of further fluid deficits. Protracted GI losses, as with vomiting, may lead to potassium depletion. Initial fluids should include a bolus of isotonic fluid (20 cc per kg), then changed to D5–0.5NS with 10 to 20 mEq per L of potassium. These fluids can then be altered, if necessary, once the serum chemistries are known. Antibiotics should be administered if perforation is suspected or there is any concern for peritonitis. Antibiotics are generally given perioperatively but timing should be discussed with the surgeon.

The emergency physician must keep in mind the many variations in the way appendicitis can present. Patients with equivocal findings should be admitted for monitoring and serial examinations or have imaging studies to demonstrate a normal appendix. If the imaging studies are equivocal, the surgeon will decide to operate or continue to monitor. Patients who have a typical history for appendicitis but suddenly have diminished pain may actually represent perforation of the appendix. Such patients should be observed for several hours before declaring an improved condition. Even in the presence of negative imaging studies, the emergency physician should arrange close follow-up for any patient with abdominal pain. For those patients with progressive pain, significant pain requiring narcotic medications, or persistent emesis, admission for further care and subsequent evaluation might be necessary.

PERFORATED APPENDICITIS

Goals of Treatment

When a perforated appendicitis is suspected, surgical consultation should be obtained promptly and adjusted for the stability of the patient. Early restoration of intravascular volume, correction of electrolyte derangements, pain control, and antibiotics are essential parts of early care. In collaboration with surgery colleagues, decisions about which patients need immediate operative care versus advanced imaging can be discussed. When an abscess is identified, the surgeons will determine the need for a drainage procedure in addition to antibiotic therapy prior to a delayed appendectomy. Short-term treatment outcomes include clearance of the intraperitoneal infection while limiting the duration of hospitalization and the need for repeated imaging or drainage procedures.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

Ideally, once the diagnosis of appendicitis is considered seriously, the patient will have an accurate diagnosis and surgery before the appendix has perforated. Unfortunately, some patients, particularly younger children, may arrive for emergency care with an already perforated appendix because of a delay in seeking treatment or in making the diagnosis. Although the time to perforation is variable, the time prior to presentation is the more important determinant of perforation and not the time of evaluation in the ED. Once the appendix has perforated, there may be signs of generalized, rather than localized, peritonitis. In a young child, the omentum is thin and often incapable of walling off the inflamed appendix. As a result, perforation leads to a more disseminated infection. Although the mortality from appendicitis has decreased, the incidence of perforation in children has remained the same over the last several decades.

Clinical Assessment

Within a few hours after perforation has occurred, the child begins to develop increasing signs of peritonitis and toxicity. First, the lower abdomen and then the entire abdomen become rigid with extreme tenderness. Bowel sounds are sparse to absent. Other signs include pallor, dyspnea, grunting, significant tachycardia, and higher fever (39°C to 41°C [102.2°F to 105.8°F]). Rarely, the patient may develop septic shock from the overwhelming infection.

Initially, the findings may be confused with those of pneumonia because the extreme abdominal pain may cause rapid shallow respirations, painful respirations associated with grunting, and decreased air entry to the lower lung fields. In young children, the findings may also be confused with meningitis because of paradoxical irritability—any motion of the child, even trying to comfort the child, may cause pain and irritability.

The laboratory findings in the child with perforated appendicitis often suggest this diagnosis. The WBC count is significantly elevated, usually higher than 15,000 per mm3, with a marked shift to left; leukopenia may be seen with perforation when associated with overwhelming sepsis.

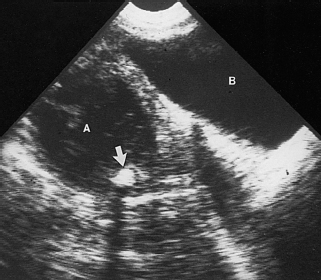

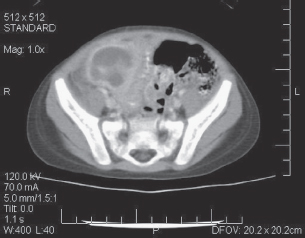

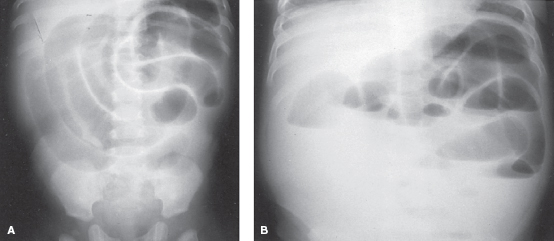

The radiologic evaluation of suspected perforated appendicitis should include plain abdominal radiographs and either US, CT, or MRI. The plain film of the abdomen may show free air or evidence of peritonitis (Fig. 124.1). The US of the pelvis may show a complex mass with or without a calcified fecalith or free fluid within the abdominal cavity (Fig. 124.2). CT is generally performed with intravenous and enteral contrast to define the size and location of an associated abscess (Fig. 124.3). MRI is now being used by some centers although it is not well studied in pediatric appendicitis.

Management

Initially, therapy should be directed toward proper resuscitation with assessment and management of the airway, breathing, and circulation. Extremely ill children may require endotracheal intubation in cases of shock. Hypovolemia should be rapidly corrected with normal saline or Ringer lactate solution. An initial bolus of fluid starting at 20 to 60 mL per kg is given rapidly until vital signs are improved and the patient produces urine. Vasopressor therapy should be considered for patients who do not have sufficient response to 60 to 80 mL per kg of isotonic fluids. Broad-spectrum antibiotics targeting bowel flora (gram-negative enterics as well as anaerobes) should be given. Immediate surgical consultation is necessary. Placement of a bladder catheter and central venous access with measurement of central venous pressure may be necessary to monitor response to therapy. Once the patient is more stable, the surgeons generally request advanced radiologic imaging to guide next steps.

FIGURE 124.1 Perforated appendicitis with abscess and fecalith. The upright abdominal roentgenogram shows numerous dilated loops of bowel and a calcified fecalith (arrow). Note that the space between the individual loops indicates the presence of intraperitoneal fluid.

Once the emergency physician is certain that the airway can be controlled and the circulation is adequate, relief of pain can be accomplished by using narcotic agents (e.g., morphine 0.1 mg per kg). The patient’s fever can usually be controlled by antipyretics or cooling blanket. A nasogastric tube should be placed to evacuate the contents of the stomach and to drain ongoing gastric secretions.

Children with perforated appendicitis can deteriorate quickly. Therefore, emergency resuscitation should be quickly followed by operative intervention in extremely ill patients. For patients with a perforated appendicitis with minimal systemic signs, abscesses may be treated with antibiotics and possibly drained percutaneously using radiologically guided procedures—with the expectation of a delayed appendectomy.

FIGURE 124.2 Perforated appendicitis with abscess and fecalith. Ultrasonography of the pelvis shows a complex mass (A) with a fecalith (arrow) producing characteristic acoustic shadowing to the right of the bladder (B).

FIGURE 124.3 CT scan of perforated appendix with abscess.

ACUTE INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION

Goals of Treatment

When intestinal obstruction is suspected, early surgical consultation should be obtained. Signs of obstruction with shock or evidence of ischemic bowel is a surgical emergency. Although diagnostic studies to identify the exact etiology of obstruction are generally valuable to direct management, a fraction of cases need exploratory surgery to rescue the bowel and prevent further deterioration of the patient.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Bilious emesis in a neonate should be considered a surgical emergency

• Although diagnostic studies are helpful to identify the cause of obstruction, critically ill patients or those with evidence of ischemic bowel may need exploratory surgery

• Tachycardia, blood per rectum, and acidosis are potential indicators of ischemic bowel

Current Evidence

In any child with persistent emesis, especially with bilious emesis, acute intestinal obstruction must be considered. If the obstruction is high in the intestinal tract, the abdomen does not become distended; however, with lower intestinal obstruction there is generalized distension and diffuse tenderness, usually without signs of peritoneal irritation. Only if the bowel perforates or vascular insufficiency occurs will signs of peritoneal irritation be present. If complete obstruction persists, bowel habits may change, leading to complete obstipation of both flatus and stool. All patients with suspected bowel obstruction should have radiographs of the abdomen in supine and upright (or lateral decubitus) views. In patients with acute mechanical bowel obstruction, multiple dilated loops are usually seen. Fluid levels produced by the layering of air and intestinal contents are seen in the upright or lateral decubitus radiographs (Fig. 124.4).

Intussusception

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Triad of bilious emesis, abdominal mass, and blood per rectum is seen in only 20% of cases

• Intussusception should be considered in infants and toddlers with emesis and altered mental status

• Children with intussusception may arrest during a pneumatic reduction and therefore the clinical team must be prepared.

• After successful enema reduction, intussusception recurs in approximately 5% of cases in the first 48 hours.

Current Evidence

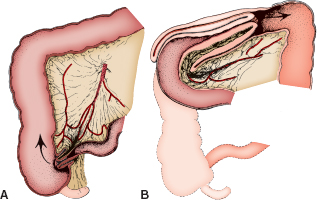

Intussusception occurs when one segment of bowel invaginates into a more distal segment. This is the leading cause of acute intestinal obstruction in infants, and it occurs most commonly between 3 and 12 months of age. The most common intussusception is ileocolic but the small bowel may intussuscept into itself. Typically, this small bowel intussusception then prolapses through the ileocecal valve (Figs. 124.5 and 124.6). The intussusception continues through the colon a variable distance, occasionally as far as the rectum, where it can be palpated on rectal examination. Colocolic intussusceptions are rare. In infants, the lead point for the intussusception may be hypertrophied Peyer patches. In children older than 2 years of age, a specific lead point such as a polyp, a Meckel diverticulum, an intestinal duplication, or a tumor should be considered. A diarrheal illness or viral syndrome may occur several days to a week before the onset of abdominal pain and obstruction. Henoch–Schönlein purpura has been associated with intussusception (generally small bowel-small bowel).

FIGURE 124.4 A: Small bowel obstruction. Numerous dilated small bowel loops occupy the midabdomen and have a stepladder configuration. Minimal air is seen in the rectum. B: Same patient as in (A). The upright abdominal roentgenogram shows numerous dilated loops in the small bowel with differential fluid levels in one loop indicating mechanical bowel obstruction.

FIGURE 124.5 Ileocolic intussusception. A: Beginning of an intussusception in which terminal ileum prolapses through ileocecal valve. B: Ileocolic intussusceptum continuing through the colon. This can often be palpated as a mass in the right upper quadrant.

FIGURE 124.6 Ileocolic intussusception. Barium enema shows the intussusception as the filing defect within the hepatic flexure surrounded by spiral mucosal folds. Significant distended small bowel represents distal small bowel obstruction.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition. The primary manifestation of intussusception is colicky abdominal pain in an infant or toddler. Children with vomiting, especially if bilious, and intermittent abdominal pain should be evaluated for intussusception. The condition of the patient is highly variable between being happy and playful between episodes to critical ill children with evidence of peritonitis and shock. Occasionally, the primary complaint may be blood per rectum or vomiting and altered mental status.

Triage Consideration. Blood per rectum or bilious emesis in a child with possible intussusception should be triaged to an acute room with immediate assessment by the emergency department team. Children with evidence of shock or bowel obstruction may need immediate operative care.

Initial Assessment. Most children present with significant intermittent abdominal pain. This symptom may have been preceded by the symptoms and signs of a viral gastroenteritis or even an upper respiratory infection. Gradually, the child becomes more irritable and anorectic, and may vomit. The pattern of pain in a child with an intussusception is often consistent and characteristic, and the diagnosis is suggested strongly if a history of episodic pain is obtained. The child may appear to be comfortable and well between episodes. Occasionally, the infant may appear lethargic and listless. At times, patients with intussusception have been misdiagnosed as being in a postictal state or encephalopathic.

The localized portion of the intussusception leads to partial or complete obstruction and generalized abdominal distension. In some cases, the intussuscepted mass can be palpated as an ill-defined, sausage-shaped structure if the abdomen is not too distended. This mass is most often palpable in the right upper quadrant.

When children arrive in the ED early in the course of intussusception, there is often no history of having passed a currant jelly stool, although blood may be found on rectal examination (50% to 75% of cases have occult blood). However, the absence of bloody stools should not preclude making the diagnosis of a possible intussusception. Infants and young children with colicky abdominal pain and emesis should be evaluated for intussusception. Only 20% of infants with intussusception have the triad of colicky abdominal pain, abdominal mass, and bloody stools.

As the bowel becomes more tightly intussuscepted, the mesenteric veins become compressed, whereas the mesenteric arterial supply remains intact. This leads to the production of the characteristic currant jelly stool, which may be passed spontaneously or found on the rectal examination. As the intussusception becomes swollen, the pressure of entrapment occludes the arteries. At this point, the bleeding lessens, but the bowel can become gangrenous and even perforate, leading to peritonitis.

Management. The patient should receive IV fluids to correct dehydration. Surgery should be consulted immediately if the patient is critically ill or has signs of peritonitis. Nasogastric suction minimizes the risk of vomiting and aspiration if the child is critically ill. Once perfusion is improved and blood has been sent for CBC, electrolytes, and a blood bank sample, the patient should have diagnostic imaging.

Plain radiograph findings of intussusception are variable and depend primarily on the duration of the symptoms and the presence or absence of complications. In early cases, a normal gas pattern is seen. Distal colonic air cannot be interpreted as an absence of intussusception. Unless the radiograph exhibits air in the cecum, ileocolic intussusception cannot be excluded by radiograph. To improve yield, some centers utilize prone films or left lateral decubitus radiographs to enhance air movement into the cecum. In the patient with symptoms longer than 6 to 12 hours, flat and upright films often show signs of intestinal obstruction, including distended bowel with air–fluid levels (Fig. 124.4). A characteristic “target” sign may be seen or more commonly a paucity of gas in the right lower quadrant. Occasionally, the actual head of the intussusception can be seen on a plain film as a soft tissue mass.

US can be used diagnostically with reported sensitivity of 98% to 100%. Whether all patients should have plain films prior to US is debatable. If signs of intestinal obstruction or peritonitis, plain films may demonstrate pneumatosis or free air and thereby expedite operative care. Oftentimes, the radiologist may request a plain film prior to enema reduction but not necessarily before US.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree