ABDOMINAL DISTENSION

JEFFREY R. AVNER, MD, FAAP

Distension may occur in any structure that has an encircling and restricting wall; abdominal distension is generally defined as an increase in the breadth of the abdominal cavity. Often, the distension is large and thus easily noticeable to the child or parent. However, subtle increases in abdominal girth may be first appreciated by the child’s sensation of abdominal pressure, fullness, or bloating. In general, abdominal distension is often due to an increase in intra-abdominal volume by air, fluid, stool, mass, or organomegaly. Nevertheless, care should be taken not to confuse true abdominal distension with certain conditions that cause an apparent increase in abdominal girth such as poor posture, the natural exaggerated lordosis of childhood, abdominal wall weakness, obesity, and pulmonary hyperinflation. Examination of the patient in both the supine and upright positions assists the clinician in recognizing these factors before considering diagnoses that truly increase the volume of the abdominal cavity.

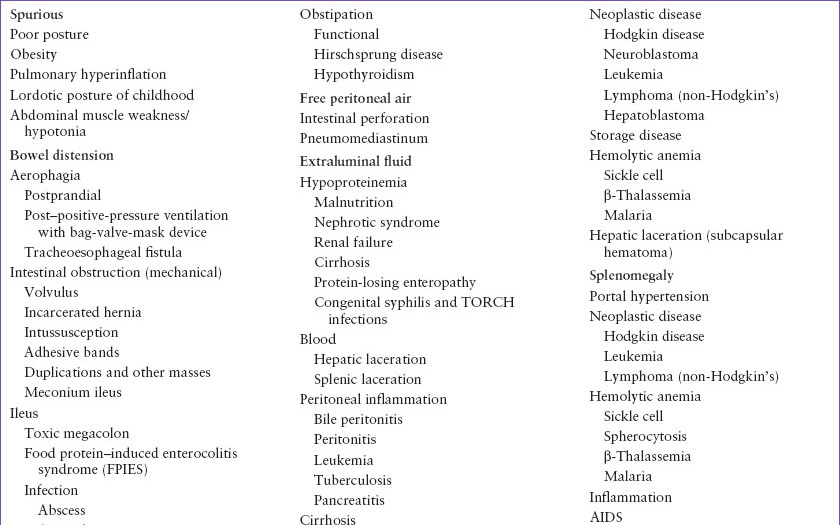

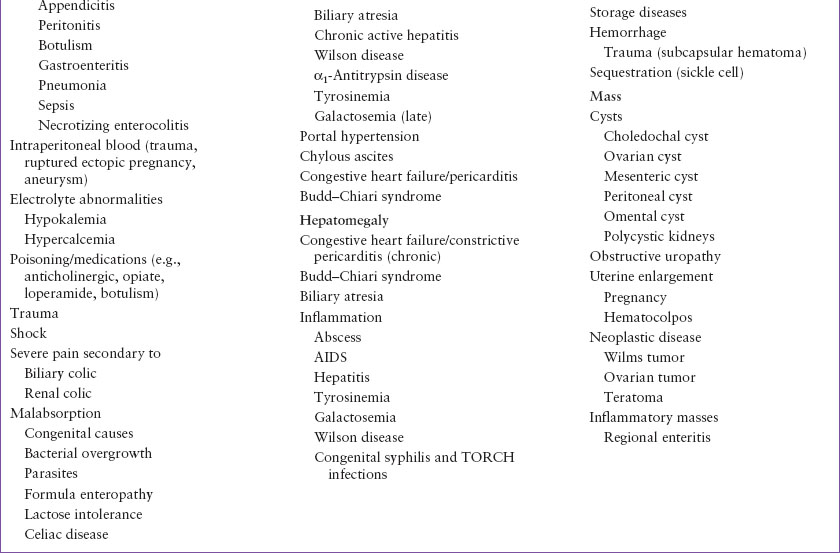

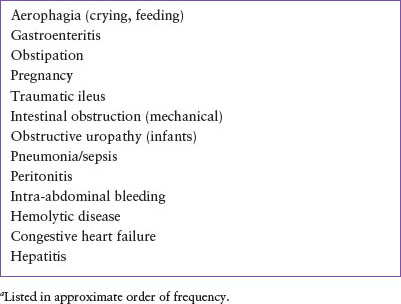

Abdominal distension is a nonspecific sign. That is, the causes of abdominal distension are numerous (Table 7.1). Even when the discussion is limited to the more common causes (Table 7.2) or emergent and urgent causes of abdominal distension (Table 7.3), the list is long. When confronted with a patient with abdominal distension, one approach is to divide the causes into the following generic categories: distended bowel, extraluminal gas (e.g., free air), extraluminal fluid, massive hepatomegaly, massive splenomegaly, and other causes (e.g., mass, cyst, pregnancy). This categorization is more easily described on paper than discerned at the bedside. A large cystic mass can be easily mistaken for ascitic fluid. A Wilms tumor may feel much like splenomegaly. Another difficulty in the clinical application of this categorization is that many pathologic processes that lead to abdominal distension do so through several of the previously mentioned categories. For example, kwashiorkor causes abdominal distension secondary to hepatosplenomegaly and ascites. For these reasons, the reader is urged to regard this initial categorization, when used at the bedside, as tentative, pending confirmation from plain radiograph, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or other imaging studies.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Bowel distension occurs secondary to mechanical or functional intestinal obstruction, aerophagia, malabsorption, or obstipation. Mechanical obstruction most commonly occurs in infants secondary to congenital malformations (atresia, volvulus, Hirschsprung disease), incarcerated hernia, duplication cysts, or intussusception. At any age, a history of previous abdominal surgery usually suggests intra-abdominal adhesions as the cause of intestinal obstruction. The amount of bowel distension is often related to the level of obstruction. After several hours, most of the gas distal to the obstruction is passed, leaving an airless segment distally. Therefore, the lack of air in the rectum and sigmoid colon on a prone cross-table lateral radiograph of the abdomen supports the diagnosis of mechanical obstruction. Functional obstruction, or paralytic ileus, is suggested by tympanitic abdominal distension with the absence of bowel sounds. In general, all parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are dilated, but the colon is usually more distended than the small intestine. Paralytic ileus may occur secondary to numerous causes. Signs such as involuntary guarding and pain with movement suggest peritoneal irritation secondary to infection, pancreatic enzymes, bile, or blood. Fever without peritoneal signs suggests intestinal inflammation, gastroenteritis, systemic infection, or anticholinergic poisoning (see Chapters 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies and 110 Toxicologic Emergencies). Various poisonings (atropinics), toxins (botulism), antimotility drugs (loperamide), and metabolic abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, uremia, acidosis) may also result in an ileus. These will most likely occur in the patient who has no abdominal findings other than tympanitic abdominal distension. In these cases, the abdomen is usually distended but nontender. Toxic megacolon, an extensive dilatation of the colon, is a potentially fatal complication of severe colitis. Children with toxic megacolon appear ill and have abdominal distension along with diarrhea, pain, fever, dehydration, and possibly sepsis. Similar clinical symptoms are seen with enterocolitis, which may present as a life-threatening complication of Hirschsprung disease. Infants with acute food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), a non–IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity, present with profuse emesis soon after ingestion of the trigger food, followed by lethargy, diarrhea, abdominal distension, and, in severe cases, hypotension. It is important to note that some conditions such as sepsis and peritonitis may cause a combination of functional and mechanical obstruction. Finally, gastric dilatation may result from several causes, including localized paralytic ileus (due to gastroenteritis or a pulmonic process), aerophagia, and iatrogenic reasons (bag-valve-mask ventilation or esophageal intubation). The resulting gastric distension is an extremely important entity that may result in significant respiratory embarrassment secondary to upward pressure on the diaphragm unless decompressed through a nasogastric tube or other means.

Bulky, foul-smelling, or diarrheal stools suggest malabsorption secondary to many causes, which may include formula enteropathies, bacterial overgrowth, parasites, and cystic fibrosis (see Chapters 99 Gastrointestinal Emergencies and 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies). In lactose intolerance, bacterial metabolism of unabsorbed lactose produces intestinal gas causing abdominal distension, cramping, flatulence, and diarrhea. The severity of the symptoms is related primarily to the quantity of lactose ingested. Celiac disease may present with prominent abdominal distension, especially in children younger than 2 years, along with nonspecific GI symptoms and poor weight gain. Obstipation is a common cause of abdominal distension. The patient usually has a history of irregular stooling or chronic constipation. This is often due to a severe functional disturbance, but pathologic processes, including Hirschsprung disease and other defects in bowel enervation, and hypothyroidism should be excluded (see Chapter 13 Constipation).

TABLE 7.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ABDOMINAL DISTENSION

TABLE 7.2

COMMON CAUSES OF ABDOMINAL DISTENSIONa

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree