INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

This chapter reviews diagnosis and treatment of abdominal and pelvic pain in nonpregnant women. Even after the possibility of pregnancy is eliminated, abdominal pain in women remains a challenging diagnosis because of physical proximity and overlapping spinal segment innervation and similar symptoms of GI, urologic, and gynecologic organ systems. Discussion of the pregnant woman with abdominal/pelvic pain is found in chapters 100, “Maternal Emergencies after 20 Weeks of Pregnancy and in the Postpartum Period,” 103, “Pelvic Inflammatory Disease,” and 71, “Acute Abdominal Pain.”

CLINICAL FEATURES

Define characteristics of the pain including onset, duration, location, quality, radiation, and exacerbating and alleviating factors. History should include questions about GI symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation), urologic symptoms (dysuria, hematuria, frequency, and urgency), and gynecologic symptoms (vaginal bleeding, discharge, dyspareunia, and menstrual history). History of sexual activity and menstrual history should never be relied upon to exclude pregnancy. Obtain past medical, surgical, and family history, as well as details of prior pregnancies and outcomes. Active lactation and medication use, including specific methods of birth control, should be part of the history. Ask about infertility treatments because ovulation-inducing treatments increase risk of ovarian torsion, cysts, and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. When obtaining a sexual history and social history, it is wise to interview the patient alone, which may help patients feel more comfortable discussing potentially sensitive or embarrassing topics. Ask about pelvic inflammatory disease risk factors including unprotected intercourse, prior sexually transmitted infections, and multiple sexual partners. While the patient is alone, ask her about safety at home, and assess for any potential abusive situations. Patients with history of physical and sexual abuse may develop a variety of somatic complaints including abdominal and pelvic pain, and this pain is often chronic in nature. Social history should include living situation, occupation, and personal habits (use of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs).

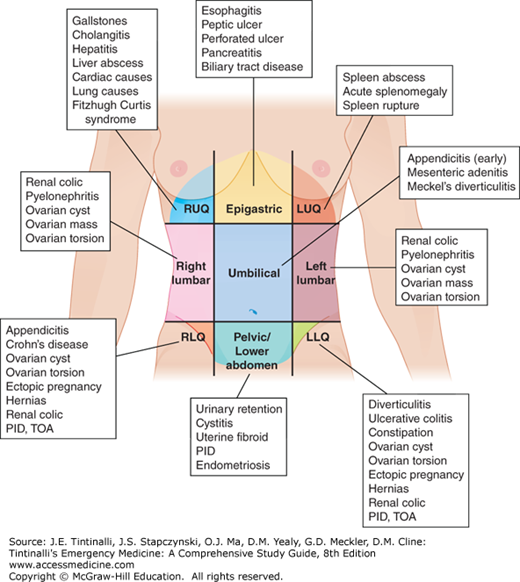

A standard head-to-toe systematic approach beginning with vital signs is essential. The patient should be adequately undressed for a careful examination. In focusing on the examination of the abdomen, it is helpful to determine in what quadrant(s) of the abdomen the pain is located; this may help to narrow the differential diagnosis (Figure 97-1).

In addition to palpating for tenderness or masses, evaluate for surgical scars, rashes, bruising, or ascites. Peritoneal signs may be less obvious in patients who are elderly, are obese, or have altered neurologic status. A digital rectal exam is helpful, if indicated, to evaluate complaints of rectal pain or bleeding.

A pelvic examination is usually a routine component of the exam of women with lower abdominal pain, but studies report a lack of accuracy and reproducibility of pelvic examination findings.1,2 Pelvic examination is useful for obtaining lab specimens for sexually transmitted infections, palpation for tenderness or mass, and to check for vaginal bleeding, discharge, or foreign body.

DIAGNOSIS

In a nonpregnant female with abdominal pain, ED testing beyond a thorough history and exam is not always mandatory. For example, in a patient with multiple prior similar presentations and recent normal imaging studies, it is unnecessary, rarely helpful, and potentially harmful to repeat imaging.3 In cases where further ED testing is determined to be unnecessary, the physician must still pay careful attention to symptom control, careful reassessment, and disposition. At the time of discharge, providers should review with the patient arrangements for close follow-up, often in 12 to 24 hours, as well as indications for return to the ED. When benign causes are not clear from the initial evaluation and concerns for serious pathology remain, lab and/or imaging tests are necessary.

Obtain a pregnancy test in all women of childbearing age who still have a uterus and ovaries. See chapter 98, “Ectopic Pregnancy and Emergencies in the First 20 Weeks of Pregnancy” for a detailed discussion of pregnancy testing. A CBC is often obtained, but the WBC count is not reliable to rule in or exclude serious disease.5 Obtain a urinalysis, and add a urine culture in pediatric patients, pregnant women, and patients at risk for complicated urinary tract infections. See chapter 91, “Urinary Tract Infections and Hematuria” for detailed discussion of urinalysis. Be cautious in making a definitive diagnosis of urinary tract infection as the sole cause of a patient’s symptoms. For further discussion, see chapter 71.

US is the imaging modality of choice for genital tract pathology (ovarian cyst, ectopic pregnancy, uterine or ovarian mass, or tubo-ovarian abcess). CT is preferred when GI or GU pathology (appendicitis, diverticulitis, bowel obstruction, or renal stones) is highest in the differential diagnosis.

Bedside US can facilitate rapid diagnosis and treatment. For example, a positive focused assessment with sonography for trauma exam could help diagnose a ruptured ectopic pregnancy or significant hemorrhage from an ovarian cyst.5 ED US can quickly identify a normal intrauterine pregnancy. Pelvic US is the primary imaging modality for evaluation of lower abdominal pain in the female patient in whom a gynecologic diagnosis is considered most likely. US is useful in diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease, tubo-ovarian abcess, leiomyoma, and ovarian cysts. In evaluation of possible ovarian torsion, pelvic US should include Doppler flow. Transabdominal and intravaginal probes are used for imaging of pelvic organs. In transabdominal imaging alone, a full bladder aids visualization of pelvic organs. In transvaginal imaging, an empty bladder aids visualization. US studies should never be delayed waiting for a full bladder, particularly when there is concern for a serious diagnosis such as ovarian torsion. US may be useful to evaluate for appendicitis, but it is less sensitive than CT and is operator dependent.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis is sensitive for evaluation of most abdominal and pelvic conditions. Usually IV contrast alone is sufficiently sensitive for evaluation of possible appendicitis.6 If there is concern for pelvic abscess, or the patient weighs less than 70 kg, oral contrast may enhance accuracy of evaluation. MRI is accurate in diagnosis of many abdominal and pelvic conditions, but cost and limited availability limit its use in most EDs.