Trauma incidents and case fatality rate by age and gender

Age Related

Trauma in the elderly is complicated by impaired hemostasis, adverse drug reactions and drug–drug interactions, and decreasing immune function. In reviews of the literature, it is clear that older adults had higher short- and long-term mortality rates than younger patients, higher in-hospital and post-hospital mortality for any given ISS, and longer overall hospital stays (Jacoby et al. 2006). In elderly patients with abdominal trauma, the mortality rate is reported to range from two to three times greater than in younger people and more than a fourfold increase in thoracic trauma mortality (Sharma 2007; Wardle 1999). Sex is independently correlated with increased mortality in older adults (Jacoby et al. 2006).

In a systematic review by Jacoby et al., investigators cited multiple studies evaluating the relationship between sex and outcome for traumatically injured elders that consistently demonstrated that men had a higher risk of mortality than women (Jacoby et al. 2006). In these studies, women were more likely than men to be alive seven to eight years after injury. While differences in immunologic function by sex may contribute to this disparity in a manner similar to that seen in younger trauma patients, other reasons more specific to the elderly population need to be considered. Elders often have comorbidities with prescribed medications that may alter physiologic responses to trauma and acute injury, especially regarding pulmonary and cardiovascular reserves. Because of this, errors in triage decisions may occur when vital signs do not accurately reflect the severity of the patient’s acute injury. Vital signs can be altered by cardiac and antihypertensive medications masking hypovolemia and early shock or exacerbating minor insults. Response to injury can be adversely affected by pharmacologic or physiologic alterations in hemodynamics and coagulation. Nevertheless, all of the difference in outcomes by sex in elderly trauma patients cannot necessarily be attributed to medications. In a study of nursing home patients in Israel, there was no difference in the number of different medication by sex, but the number of medications did increase with patient’s age (Beloosesky et al. 2013). In a study in US nursing homes, elderly women were only slightly more likely than men to be taking more than nine drugs (OR 1.1, 95% CI, 1.00–1.20) (Dwyer et al. 2010). When only the most commonly prescribed medications were considered, there was no difference between the sexes. Patients taking more prescription medications have a greater risk of adverse drug reactions. Medications such as anticoagulants, antihypertensives, and sedatives can adversely affect an elderly patient’s ability to cope with trauma. Nevertheless, no evidence shows a significant difference between sexes in the number or types of medications that elders take (Nguyen et al. 2006).

Variances in the prevalence of types of medical problems are another consideration that might contribute to differences between the sexes in injury presentation and outcomes in elderly patients. For example, osteoporosis is more common in elderly women and is associated with an increased risk of fractures from trauma. Elderly women are more likely than men to sustain rib fractures; however, the likelihood of mortality from these rib fractures was 2.35 (95% CI, 1.1 – 5.7) times higher in men. Likewise, the mortality and morbidity of hip fractures are widely reported with a large sex discrepancy among these patients. More than 75% of those sustaining hip fractures are women, likely due to the effects of osteoporosis (Jordan and Cooper 2002). First-year mortality statistics range from 12% to 37%, likely related to anatomic location (Wolinsky et al. 1997). Significant mortality has been attributed to exacerbations or complications of preexisting conditions. Less than half of patients sustaining a hip fracture return to their baseline functional status (Keene et al. 1993). Younger patients who have been severely injured and have preexisting medical conditions also have increased mortality rates that have been reported to be twice those seen in equivalently injured healthy patients (Morris et al. 1990).

Pregnancy

A discussion regarding sex-based differences in trauma would be remiss in neglecting the obvious care-related issues that arrive when treating the pregnant patient. The management of trauma in pregnancy and the delineation of injury patterns in pregnant women have been extensively studied and reported in the literature. As is the case in all trauma patients regardless of sex, blunt trauma is more prevalent that penetrating trauma in pregnant women. Women are more likely to suffer intimate partner violence (IPV) during pregnancy. Therefore, emergency health care providers must have a higher index of suspicion for IPV and should systematically screen all pregnant patients presenting for the evaluation of an injury or vague illness. Such interventions have been demonstrated to decrease the effects of IPV and to improve pregnancy-related outcomes (Kiely et al. 2010).

In the United States, trauma is the leading cause of death in pregnant women (Fildes et al. 1992). Surprisingly though, some studies have reported that pregnant women have a lower mortality rate than nonpregnant women presenting with similar injury severity and injury severity scores (John et al. 2011). This can be understood by the fact that traumatic injury proportionally causes the most deaths during pregnancy.

Procedures commonly performed on trauma patients in the emergency department require special consideration in the traumatically injured pregnant woman (Figure 6.2). While an in-depth discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter, it is crucial to recognize that anatomy and physiology change throughout gestation, and the emergency health care provider must keep these changes in mind when evaluating the patient or planning a procedure. For example, when placing a chest tube in women in the third trimester of pregnancy, the tube must be inserted one intercostal space above the usual site of insertion between the fourth and fifth ribs to avoid injuring the diaphragm that is elevated because of the size and position of the gravid uterus. Pregnancy-related alterations in evaluation and treatment must be studied and practiced by the emergency health care provider prior to confronting a crashing pregnant trauma patient so that habits of muscle memory and routine do not interfere with the rendering of effective care in critical situations.

| Estimation of fetal age by physical exam or ultrasound | Uterine fundus at umbilicus equals about 22 weeks gestation |

| Determine Rh status if bleeding | Consider Rhogam in Rh negative mother |

| Understand implications of gravid uterus on procedures and anatomy | Changes in FAST scan and landmarks to be used in procedures like tube thoracostomy |

| Do not limit diagnostic and resuscitative efforts in the setting of pregnancy | Utilize CT and x-ray per usual protocol to diagnose traumatic injury in pregnant patients |

Keys to resuscitation of the traumatically injured pregnant woman

Beyond routine trauma care, the emergency health care provider should be prepared to perform the following additional critical interventions for the pregnant trauma patient: establishment of fetal age (changes in physical exam), maintaining patient in a left lateral decubitus position (to decrease effect of uterus on inferior vena cava), determination of Rh status (administration of rhogam as indicated to prevent subsequent fetal hydrops), carrying out all appropriate imaging for the type and severity of injuries in the same manner and as thoroughly as would be done in the nonpregnant trauma patient (care of fetus is predicated on care of mother), and screening for intimate partner violence (Zelop 2013).

Immunology/Hormones

Some of the most interesting and important research on sex differences in trauma patients has focused on the effects of hormones. Several studies have reported menstruating women who suffer a traumatic injury or sepsis have increased survival rates. The immune function of women who are immediately preovulatory remains fully active after severe trauma, in contradistinction to young men and oophorectimized or postmenopausal women, whose immune function is impaired after significant trauma (Choudhry et al. 2007). One explanation of this phenomenon is that estradiol enhances cell-mediated and humoral immunity while androgens suppress the immune system. In animal models, castration has been shown to improve survival after trauma. Premenopausal women are less likely to develop many of the life-threatening complications of trauma, such as adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pneumonia, sepsis, pulmonary emboli, or acute renal failure. However, women who develop these complications have a greater case fatality rate than men. Women with any of these complications have an odds ratio of death of 1.2 compared to men. If they avoid these complications, they are 26% less likely to die from similar traumatic injuries than men (Haider et al. 2009).

Sex hormones may be important therapeutic options in trauma. However, interpreting their significance in certain populations can be complicated by exogenous hormone intake and clinical human studies have not demonstrated efficacy (Angele et al. 2012).

LGBT Patients

The emergency health care provider must be aware of the more common hormone regimens used by transsexual patients and the implications of those regimens on the morbidity and mortality related to trauma. Male patients transitioning to female use combinations of antiandrogens, GnRH agonists, and estrogens, which, theoretically, could improve their survival from traumatic injury if the data demonstrating the relationship of mortality from traumatic injury to hormonal changes associated with the menstrual cycle can be extrapolated to exogenous hormone ingestion (Gooren and Tangpricha 2013). However, hormones supplements for gender transition are not always taken as prescribed by physicians, or not always purchased in pharmacies. They can be acquired online from vendors whose sources are unregulated and may lack quality control and testing. Providers should be aware of potential complications of exogenous hormone ingestion, such as increased rate of venous thromboembolic events and accelerated cardiovascular disease. Females transitioning to male use androgen therapies such as testosterone. Sex hormones in these cases are, of course, not being taken by the patient to improve outcomes in trauma and sepsis but may have a significant pejorative effect on outcomes.

Traumatic Brain Injury

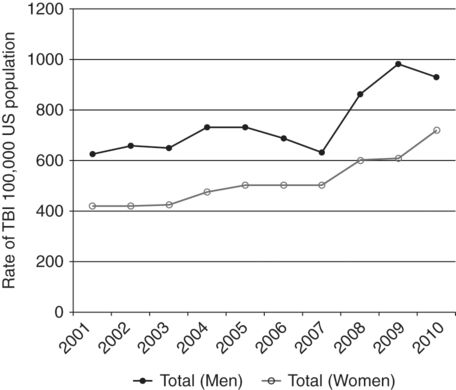

The rates of TBI related to ED visits increased in 2010 for both men and women (Figure 6.3) (Centers for Disease Control 2011b). A recent study showed that women who had sustained a TBI during the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle, when progesterone levels were high, had lower quality of life health-rating scores than women who sustained a TBI when progesterone levels were low and estrogen was high (Wunderle et al. 2013). When examined in a murine model, all female mice suffering from TBI survived the initial injury in the acute period, as compared to 72% of the male mice. Female mice had less impairment in cerebral blood flow and better recovery than male mice. The improved survival in the females was posited to be the result of the ability of the females to maintain a higher and more consistent mean arterial blood pressure and therefore more consistent cerebral perfusion pressure in the face of elevated estrogen levels. The investigators suggest that estrogen may be neuroprotective, with beneficial effects on the cerebral microvasculature, inducing the production of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, which has an important antioxidant effect limiting oxidant-mediated damage through a direct antioxidant effect (Roof and Hall 2000).

Rates of traumatic brain injury by sex – United States, 2001–2010

Multiple other models have demonstrated improved outcomes when the brain injury was treated with adjunctive progesterone. Animal models of injury have found beneficial effects on both anatomic and functional outcomes along with decreases in associated biomarkers of injury and inflammation. Progesterone has been found to cross the blood-brain barrier and decrease levels of cerebral edema and associated expression of pro-apoptotic genes (Stein 2011). This has been followed by three small human clinical trials that, while positive, have yet to demonstrate sufficient strength of evidence to recommend progesterone therapy for traumatic brain injured patients (Ma et al. 2012). Several large, prospective clinical trials are currently being conducted in several countries that, it is hoped, will provide clear direction as to progesterone’s utility and efficacy in preventing the severe morbidity associated with TBI (ProTECT III and SyNAPSe).

Provider and Team Differences

Beyond understanding the role that sex plays in the trauma patient, it is important to consider the implications of gender differences among health care providers and in the resuscitation team. Significant research has been done investigating the qualities of skilled and effective trauma teams, including team composition and communication styles, but no studies have been done evaluating the differences between male and female trauma team leaders. Historically, men have held more leadership roles; therefore, “maleness” and masculine characteristics including competitiveness, aggression, and dominance have become associated with leadership. These characteristics may not truly be the most effective for trauma team leadership. In fact, women’s leadership characteristics such as the ability to cooperate and engender collaboration in others, manifesting and encouraging empathy, and providing emotional support to the patient and the team may be equally important or more useful in successfully coordinating a team approach to trauma management. It may be that there are greater differences between leaders of the same sex reflecting their personalities and social and emotional backgrounds than identifiable gender-based leadership characteristics (Moran 1992). Leadership qualities are generally situationally dependent. Leaders who succeed are those whose skills fit the situation or who rise to the occasion. It is not difficult to imagine that providers who choose to work in the specialties of trauma surgery or emergency medicine might have intrinsic personality-based leadership characteristics that are not gender specific. Beyond leadership, gender seems to affect other aspects of doctor–patient interactions. For example, a study revealed that nurses (the majority of whom are women) provide less analgesia to men than to women. Conversely, physicians of both sexes are more likely to undertreat female patients in pain (Chen et al. 2008; Nevin 1996).

A study published in 2012 in the United States demonstrated a surprising bias in the triaging of injured patients to designated trauma receiving centers in countries where such centers exist. The investigators found that pre-hospital providers were more likely to transport injured men than injured women to trauma centers (41% vs. 31%, p<0.0001). This bias was maintained even after the researchers controlled for age, comorbidities, injury severity score, and bodily region injured. This bias was also seen when the investigators reported on physician decisions to transfer patients to trauma centers from non-trauma designated emergency medicine facilities (36% vs. 24% p<0.0001) (Gomez et al. 2012). The impact of this discrepancy has not been individually teased out but can be assumed to be dramatic given the demonstrated mortality benefit of 30% when direct pre-hospital transfer to a trauma center is achieved (Haas et al. 2012).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree