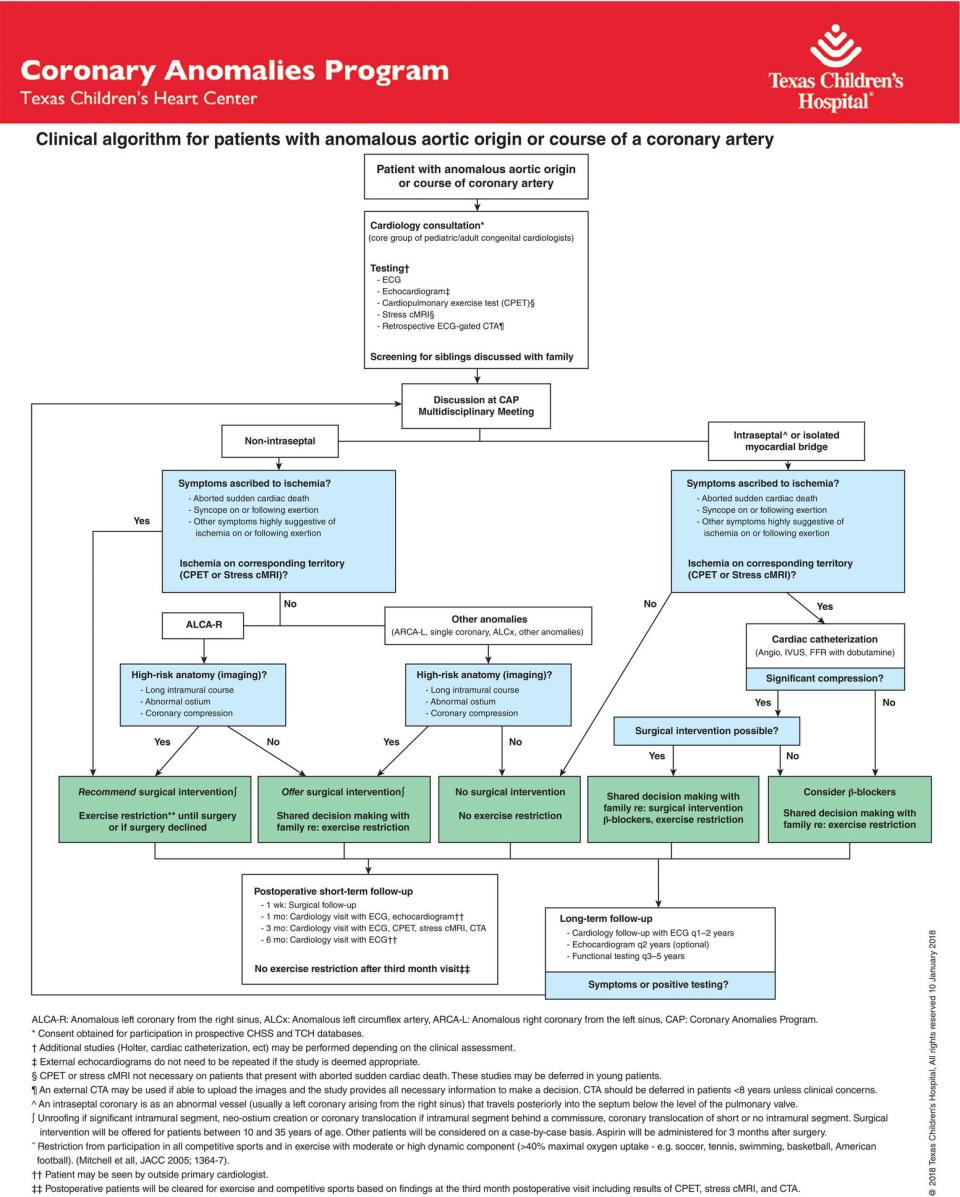

Dean B. Andropoulos Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA Caring for the patient with congenital heart disease (CHD) has become an increasingly complex endeavor, with the rapid increase in knowledge about each condition, and the diagnostic and therapeutic options available. Previously unimaginable procedures, such as a Stage I Palliation procedure for hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) being performed interventionally in the cardiac catheterization laboratory without surgery, are being contemplated and will be attempted soon [1]. Congenital cardiac care now encompasses the entire lifespan from the fetus and neonate to the adult with CHD [2]. The explosion of knowledge in pediatric and CHD makes it impossible for one practitioner, or a small group of caregivers, to possess the requisite knowledge about every condition to make an informed decision for the best care of the patient. Newer procedures such as transcatheter pulmonary and aortic valve replacement, stenting or occlusion of the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in small infants, and a variety of new short‐ and long‐term mechanical support devices have radically changed the older approaches to many lesions and clinical scenarios which formerly had been well established [3, 4]. There is a profusion of outcome studies of all of these new approaches published every year, and it is infeasible to be well versed in all of these new data. Over the past several decades, the development of pediatric and congenital cardiac anesthesiology, with a more formal and complete knowledge base, dedicated teams in many centers, and organized fellowship training now culminating in Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) certification in the United States, has given impetus for anesthesiologists to be formally involved in patient care decision‐making and leadership roles in systems of care [5]. The idea of multidisciplinary collaboration, where many experts discuss and contribute to patient care decisions and reach a consensus, has evolved as the desired model for many institutions, given the profound implications for outcomes and quality of life for patients. In addition, collaborative shared leadership for strategic and operational planning has emerged as a desired model in congenital cardiac care for many programs. This chapter will review the concept of a Center for care in congenital cardiac disease from the perspective of the Texas Children’s Hospital (TCH) Heart Center as an example of one possible approach to multidisciplinary collaboration of a large number of providers from many disciplines, and its evolution over 25+ years. Undoubtedly, there are many varied paths taken by different institutions to achieve their current CHD programs, and TCH is but one example [6, 7]. The congenital cardiac anesthesiologists’ essential role as not only caregivers, but also as contributors to patient care decision making, and TCH Heart Center leadership, will be highlighted. Then, important issues in communication and team functioning in the periprocedural areas will be discussed, focusing on the anesthesiologist’s role in the cardiac surgical operating rooms (OR) and catheterization laboratories, and in the handoff of information postprocedure, to the intensive care unit (ICU) caregivers. Next, additional examples of multidisciplinary programs and teams will be described. Finally, a brief discussion of the COVID‐19 pandemic on team functioning in congenital cardiac care is presented. Over the past 25+ years, Texas Children’s Hospital congenital cardiac care has evolved from a small team of one surgeon, one anesthesiologist, three perfusionists, two OR nurses, and 10–15 cardiologists (many of whom doubled as cardiac intensivists), performing 450 surgeries and 500 cardiac catheterizations per year, to the current large system of seven surgeons, 14 anesthesiologists, 60 cardiologists, and 25 cardiac intensivists performing more than 1,000 surgeries, and 1,500 cardiac catheterizations annually. What formerly was essentially 2–3 possible personnel combinations for cardiac surgery, with great familiarity of the same team working together at least several times a week, has evolved into an almost infinite number of caregiver combinations where the same team is only infrequently together. The TCH Heart Center has developed a robust system of leadership, care, and communication that has enabled this evolution, from a simple system to a large complicated organization, and now to a very large complex organization, where all personnel strive to provide a consistent, high‐quality level of care to all patients. The concept of complex adaptive systems in health care is being realized [8], where the focus is on interactions of interdisciplinary team members with each other, rather than on the characteristics of individual team members, in their ability to adapt to the many changing conditions and challenges to the organization [9]. The TCH Heart Center Executive Committee (HCEC) consists of two Co‐Directors, the Service Chiefs of Congenital Heart Surgery, and Pediatric Cardiology. Additional members include the Service Chiefs of Congenital Cardiac Anesthesiology (CCA) and Cardiac Intensive Care. Finally, a Nursing Lead, Physician Business Development lead, Hospital Administrative Director, and several Leads for Philanthropy and Public Relations complete the Committee (Table 4.1). This committee meets monthly or more often as needed, to set strategic directions and respond to current challenges. Of note, CCA has a major role “at the table” for all of these meetings and has an opportunity to contribute to all major questions facing the HCEC. The HCEC has a reporting relationship to a TCH Senior Leadership team consisting of the In‐Chiefs of the six hospital medical staff departments, and Executive Vice Presidents. Reporting to the HCEC are six multidisciplinary teams, each with representation from all major disciplines, that encompass the major priorities of the TCH Heart Center: clinical operations, research operations, teaching operations, data operations, patient and family experience, and marketplace competition. Table 4.1 Texas Children’s Heart Center multidisciplinary leadership structure The TCH Heart Center has made a commitment that every patient presenting for a potential intervention, whether surgery or cardiac catheterization, should be presented before a wide audience of Heart Center members, and the clinical decision‐making conferences are open to all members of the TCH Heart Center. The only exception is an emergency case where time does not permit broad discussion or simple diagnostic catheterization cases that are scheduled per protocol such as myocardial biopsies. There is formal Heart Center time every day, Monday through Friday, to present new cases in need of a timely decision about surgery, catheterization, or complex medical care. Presurgical planning conferences have remained a key component of congenital cardiac care for well over 50 years and are a familiar feature of most pediatric cardiology/cardiac surgery programs [10]. Traditionally this approach involved only cardiology and surgery; for example, in the author’s experience at the University of California, San Francisco, during Pediatric Residency training in the 1980s, a Cardiology Fellow would present the history and physical examination findings, and the additional data such as ECG, chest radiograph, cardiac catheterization angiograms and physiologic calculations, and laboratory data. In later years, echocardiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results were added to the data presented. After this presentation, a surgical plan was made after discussion among the (usually senior) cardiologists and surgeons. The junior members of the team were reluctant to speak and rarely did so. Duignan and colleagues prospectively evaluated clinical decision‐making in 107 consecutive patients in a joint Pediatric Cardiology‐Cardiac Surgery Conference, deeming 50% of the cases as complex [11]. Among these patients, Duignan and colleagues identified occasional patients with the same data sets that had different clinical decisions, some instances of the same complex patient being revisited, and two different treatment plans resulting. Anchoring bias (tendency to recommend procedures within one’s own field, i.e. surgery or interventional catheterization) was identified in several cases, and the lack of validated decision‐making algorithms in the field of congenital cardiac care was noted. The TCH Heart Center has attempted to minimize these issues with the following approaches. At TCH, Surgical Case Conferences reviewing upcoming cases for the week have involved anesthesiologists, intensivists, nurses, consultants, radiologists, trainees in all disciplines, and any other interested clinician in the Heart Center for over 25 years; and in pre‐COVID 19 pandemic times often over 100 people gathered in the Helen B. Taussig Auditorium to discuss and confirm, and at times alter, the surgical plan (Figure 4.1). A structured template, with a clinical presentation by the cardiology, surgery, or intensive care fellow, followed by the display of pertinent imaging findings by an echocardiographer, or cardiac MRI/CT specialist dedicated for the conference and prepared in advance, is followed by proposed surgical plan and discussion, confirming or at times changing the plan. Ninety minutes on Monday morning is allotted to the presentation of approximately 15–20 patients; requiring presentation and discussion to be efficient and accomplished in 3–5 minutes for the straightforward patients. In the COVID‐19 pandemic era, this and all large Heart Center Conferences have been converted to a videoconference format (Figure 4.2). In both settings, all attendees are encouraged to voice their opinions about the proposed plan for a case, even if they are a member of the junior faculty or trainee groups. Figure 4.1 Texas Children’s Hospital surgical case conference. (A) Pediatric cardiology fellow presenting the history and physical exam findings of a neonatal patient scheduled for cardiac surgery. (B) View of the surgical case conference audience, with chest radiograph displayed. (C) Large‐scale high‐resolution digital screens allow accurate review of angiograms from the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory. (D) Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is presented. Figure 4.2 Desktop computer view during urgent case presentation of the neonate with hypoplastic left heart syndrome requiring surgery. The echocardiogram is being discussed via videoconference during the COVID‐19 pandemic era. Additional clinical decision‐making opportunities exist for new patients, and existing patients requiring decisions about the next steps in clinical care. Further, 90 minutes each on Monday and Wednesday afternoons are allotted to two such conferences, where primary cardiologists present to representatives from Cardiac Surgery and Catheterization Laboratory, to decide on a treatment plan. A specialized conference for Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD) patients is held once a week for 60 minutes, where a multidisciplinary group discusses the unique needs of this patient group, including medical, catheter, and surgical therapy. Representatives from surgery, ACHD cardiology, ACHD ICU, anesthesia, and nursing are present in these weekly conferences. As with the other patient decision‐making conferences, the entire Heart Center is invited to attend these conferences. In addition to these formal conferences, each day starts with a morning report where the entire Heart Center can attend; after a brief review of the inpatient Heart Center census and planned admissions and discharges there is an opportunity to present newly admitted patients, or patients otherwise in need of clinical treatment decisions urgently (within 24–48 hours) who cannot wait for the formal case conferences (Figures 4.2 and 4.3). As with the formal planning conferences, any attendee is encouraged to speak up and voice their views on a proposed treatment plan, and at the end of the presentation, a consensus is reached about the planned treatment. These presentations often result in cases added to the surgical or catheterization schedule the same day as the presentation. For example, on the day of this chapter writing, an infant with tetralogy of Fallot, and PDA stent with cyanotic spells was presented in morning report, and dilation of PDA stent vs. surgery was discussed, the consensus was for surgery and successful repair was accomplished that day. This system of clinical decision‐making has evolved as the TCH Heart Center has grown in numbers of cases handled and personnel available, so that every patient has the advantage of the collective experience and wisdom of the entire Heart Center through a transparent process striving to attain consistency in decision‐making, e.g. all patients with the same condition will receive the same or similar treatment plan, that is data and outcomes‐driven and widely known to all who have an interest. The above‐noted Surgical Case Conference is an opportunity for a second review to confirm the surgical plan before the patient enters the OR and occasionally results in a change in the plan. Periodically, through additional Heart Center quality conferences noted below, outcome data for major lesions or other lesions of interest are reviewed, both for local cases, for large databases such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ Congenital Heart Surgery Database, and recently published literature. Through this process, a consensus is reached to change approaches to specific lesions. Two recent examples include the decision to move to primary stenting of the PDA for most neonates with right‐sided obstructive lesions in need of a stable source of pulmonary blood flow instead of a Blalock‐Taussig‐Thomas shunt; and transcatheter occlusion of the PDA in premature and other small neonates instead of ligation by thoracotomy. Figure 4.3 Morning report. (A) An overview of heart center census and non‐scheduled admissions. ACHD, adult congenital heart disease unit; AS, aortic stenosis; ASD, atrial septal defect; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; CICU, cardiac intensive care unit; CoA, coarctation of aorta; CPCU, cardiology‐cardiac surgery inpatient ward; CVOR, cardiovascular operating rooms; DORV, double‐outlet right ventricle; EC, emergency center; FTT, failure to thrive; GI, gastrointestinal; HIE, hypoxic‐ischemic encephalopathy; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; MIS‐C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with COVID‐19; PVS, pulmonary valve stenosis; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; RRT, rapid response team; SOB, shortness of breath; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; VSD, ventricular septal defect (B) Anticipated admissions and discharges to inpatient units, and scheduled clinic visits. CHS, congenital heart surgery; ECHO, echocardiography laboratory; OP, outpatient; SDA, same‐day admission. Although the field of validated decision‐making algorithms in CHD is relatively new, one example is an approach developed at TCH for Anomalous Aortic Origin of the Coronary Arteries (AAOCA), where the three treatment strategies are: observation without exercise restriction; exercise restriction; and surgical intervention [12]. Using decision analysis, a formal quantitative approach that analyzes different management strategies under conditions of uncertainly, an algorithm was developed utilizing outcomes from the published literature, and individual patient characteristics such as age and symptomatology. Life expectancy and quality‐adjusted life expectancy were the outcomes, and a cohort of 10,000 hypothetical identical patients underwent a first‐order Monte Carlo simulation, with further sensitivity analyses. Surgery was the preferred management strategy for most patients under 30 years of age for anomalous left coronary artery; and for patients <25 years of age for anomalous right coronary. Utilizing the principles proposed in this algorithm, 47 of 163 patients with AAOCA underwent surgery; 82% of the entire group was allowed unrestricted sports exercise activity; and of the surgical patients, 3 (6.4%) are restricted from sports exercise activity(Figure 4.4) [13]. All patients in the cohort were alive, whether they underwent surgery or not, during the follow‐up period. The formation of a multidisciplinary team, with support from clinical data science specialists, is key to the success of this program. Because of the early start to the surgical cases and the additional early morning conferences, the practice of rounding on surgical patients in the Cardiac ICU (CICU) at 6:15 AM Monday–Friday has been practiced for many years. This has resulted in a large group of surgeons, surgical trainees, advanced practice providers, CICU physicians and trainees, nursing leadership, the bedside nurse, and even the parents present in (or mostly outside in the hall) the CICU, traveling from patient to patient. A brief, standardized presentation by the ICU, surgical, and nursing providers for the patient was followed by surgical plans, i.e. removal of the chest tubes, pacing wires, sternal closure, etc. for the day. It was typical to have limited sight and hearing lines to the presenter, the patient, the displayed radiographs, and the physiological monitors. The COVID‐19 pandemic has prevented the gathering of large groups near the bedside and given rise to some novel methods to present the patient’s data to a multidisciplinary group. At the time of this writing, Surgical Rounds are conducted over videoconferencing with all participants (20–40 on most days) logged in at their respective desks. The presenters communicate the data, while the chest radiograph and real‐time physiologic monitoring data are displayed on the screen (Figure 4.5). Joint decisions are made about surgical and major ICU issues, with all participants able to see and hear all the data, and with the ability to speak up to allow their perspectives to be communicated. The process is also more efficient in this manner, with as many as 30–40 active surgical patients presented in the allotted 45 minutes. The entire Heart Center is invited to these rounds, as with all of the other major patient care conferences. The TCH Heart Center has several patient care Quality and Outcomes Improvement Conferences, which are protected in a legal framework from disclosure and outside discovery, allowing detailed and frank discussion of quality issues. Most of these conferences include the entire Heart Center on the invitation list. Figure 4.4 Texas Children’s Hospital Heart Center Coronary Anomalies Program Algorithm for patients with the anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery. Figure 4.5 Videoconference screen during surgical rounds on a patient on ECMO support. The surgical fellow is presenting data while chest radiograph and real‐time monitoring data are displayed during the COVID‐19 pandemic era. Figure 4.6 Performance rounds infographic. Time in days is displayed on the horizontal axis; risk level on the vertical axis; and details of the operative course are reported. The upper right‐hand corner displays the major event prompting discussion; in this case, an arrhythmia requiring readmission to ICU which was recognized and treated appropriately. Note the stepwise decrease in risk level until postoperative day 7. Once per week a 60‐minute meeting is devoted to Performance Rounds, where selected patients from surgery or the catheterization laboratory are presented in a standardized, visual, infographic time‐based format where the horizontal axis is time (days) and the vertical axis is the perceived risk level to the patient, from threats, errors, unintended clinical states and their linkage; risk increases with the intensity of the activity and decreases with the de‐escalation of care (Figure 4.6). Increased risk is conferred during surgery, generally the highest risk state in a patient’s journey, and decreased with tracheal extubation, sternal closure, weaning off inotropes, discharge to ward, and discharge to home. Data is collected from electronic medical records, bedside data, adverse event reporting mechanisms, and staff interviews. This approach was described by Hickey and colleagues, who reported on 524 patient care “flights” surrounding a surgical procedure [14]. In 12% of flights the patients failed to de‐escalate sequentially, and in the timeframe expected, through the risk levels. Failed de‐escalations were strongly associated with errors (426 in 257 flights, p < 0.0001). More serious errors were associated with the 29% rate of failed de‐escalation, vs. 4% in flights with no consequential error (p < 0.0001). Using this process at the TCH Heart Center, outcomes data for the major procedures have been developed, both internal center‐specific outcomes, and from national databases such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ Congenital Heart Surgery Database. A team of outcome specialists develops the infographics and presents the data, and the entire Heart Center staff is invited. In recent years interventional cardiac catheterization procedures have been added to Performance Rounds. Before these rounds, the themes of psychological safety (see below), and confidentiality of the privileged patient care information are emphasized. Surgeons’, cardiologists’, and anesthesiologists’ names are listed on the infographic, and they are encouraged to explain any unexpected events for the benefit of the entire Heart Center, with the goal of collective learning, communication, and improving patient care, and not to direct blame to the individual practitioner. Themes and issues that are identified, i.e. communication errors, delayed care, technical errors, decision‐making errors, etc., are discussed, and if emerging patterns are perceived over multiple patients, they are referred formally to the Quality and Outcomes Team for a deeper dive into causes and solutions. These issues are brought back to the Heart Center for updates on changes to processes and outcomes. Routine simple surgery or catheterization laboratory cases, without unexpected progress in de‐escalation, are presented in a list format but not otherwise discussed. Once per week a 60‐minute conference is devoted to quality and outcomes data and reports from each of the clinical disciplines in the Heart Center, on a rotating basis. This includes a Surgical Morbidity and Mortality conference, Catheterization Laboratory Quality Conference, CICU Quality and Outcomes presentation, Cardiovascular Anesthesiology Quality Presentation, and presentations from Nursing, Adult CHD, Outpatient Cardiology, Echocargiography, and other components of the Heart Center clinical enterprise. Every Friday early morning, 45 minutes are devoted to a Quality and Outcomes Multidisciplinary Meeting, where only the attending physicians from Surgery, Anesthesiology, and CICU, plus a Nursing and Perfusion leader, are invited, for a discussion of each surgical case done in the past week, to review the immediate perioperative course and outcomes, communicate common important issues to the group, and give each member an opportunity to discuss their decision‐making process and how it may have contributed to the outcome. The surgeon starts by briefly presenting the case, and then the anesthesiologist and intensivist have an opportunity to add to the discussion. The smaller group is conducive to frank discussions about opportunities for improvement; identifying significant issues that affect the entire perioperative team that then can be assigned an individual to lead more data collection and solutions to the problem. Great successes are also discussed and celebrated, and those involved in the case can enlighten the group, again for the benefit of future patients. Figure 4.7 displays the calendar of the weekly multidisciplinary meetings in the TCH Heart Center. With a very large group of practitioners and supporting staff that now numbers greater than 500 individuals, it can be challenging to communicate important events, announcements, initiatives, and strategies to all Heart Center members. Quarterly Heart Center Town Halls, 60 minutes in length, are held, with the Heart Center Executive Committee leadership leading the agenda and introducing additional speakers; there are always at least 15–20 minutes left for comments and questions, and unanswered questions are addressed separately by email (Figure 4.8). Once every year, non‐emergent patient care is paused for 4 hours, and the entire Heart Center participates in a “retreat” – in reality on site at TCH. During these retreats, a theme is prepared, and after Heart Center leadership presentations, speakers from the Heart Center, or outside speakers make presentations followed by questions and comments from the audience. Once again, all Heart Center members at any level of seniority are encouraged to ask questions and make comments, for the benefit of the entire group. Some annual retreat themes have included: improving communication across silos, integrating teams and processes, transparency, psychological safety, shared decision‐making, patient/family experience, partnerships with external providers, and shared common purposes [15, 16]. In the pre‐pandemic era, several hundred people gathered in a large auditorium and enjoyed well‐prepared content, for example, presentations on psychological safety from a well‐regarded Rice University School of Business professor with substantive research in this area (Figure 4.9). In the current pandemic era, this activity is conducted by videoconference; with participants encouraged to write questions, or ask live if they prefer. Figure 4.7 Texas Children’s Hospital Heart Center Multidisciplinary Conference Schedule. Figure 4.8 Slide from recent TCH Heart Center Town Hall in the COVID‐19 pandemic era. Figure 4.9 TCH Heart Center Retreat in the pre‐pandemic era with an outside speaker presenting his research on team functioning in healthcare. TCH Heart Center anesthesiologists are often busy starting cases for the early 7–8 AM conferences and cannot attend all, but all conferences have anesthesiology representation for those without scheduled cases at that time. The anesthesiologists very often contribute to the discussion and the decision‐making process for all of these conferences and are valued full‐time members of the Heart Center team, whose opinion is often requested and is always respected. Presence and visibility at these conferences for the Anesthesiologists give them complete access and exposure to the broader Heart Center, increasing respect and affording opportunities, rather than being limited to surgeons in the operating room and interventional cardiologists in the catheterization laboratory. Having a full‐time division whose sole clinical activity is in the Heart Center also increases the reputation and trust of CCA, and affords leadership, quality, education and research opportunities that facilitate career advancement and satisfaction. In 2000, de Laval and colleagues published a landmark paper on human factors, errors, near misses, communication, and rescue from negative events in a multicenter study of 193 arterial switch operations (ASO) performed by 21 surgeons in all 16 institutions performing pediatric cardiac surgery in the United Kingdom in the late 1990s [17]. A self‐assessment questionnaire regarding performance was filled out at the end of the operation by the surgeon and surgical assistant, the anesthesiologist, perfusionist, and scrub nurse. Each case was independently observed by a human factor researcher, who wrote a detailed description of the operation, including individual and team performance, communication within and between teams, and situational and organizational data. Errors or failures were recorded and classified as minor (minor disruptions in surgical flow without consequences) or major (likely to have serious patient safety consequences) negative events. Events were also deemed compensated, or uncompensated, meaning resolved, or recovered after appropriate action by the perioperative team. There were 16 hospital deaths for mortality of 6.6% with 43 near misses (17.7%). The number of uncompensated major events per case conferred the strongest risk of death at an odds ratio of 13 (95% CI 2.1–83, p = 0.006), and for each uncompensated major event, estimated odds of death increased by a factor of 5.7, and odds of death plus near miss were increased by a factor of 40. Interestingly, the self‐report questionnaires were not successful in capturing human factors in predicting outcomes. The finding that failure to rescue from complications was strongly associated with poor outcomes is consistent across medical specialties. The list of observed major and minor events in this paper details a number of team performance problems, e.g. not communicating significant deterioration during cannulation, delay in the administration of heparin, delay in recognition of myocardial ischemia post‐CPB, incorrect interpretation of serious deterioration during transport to ICU, failure to achieve sufficient vascular access, the inappropriate delegation of anesthetic tasks to inexperienced juniors, and many others (Table 4.2

CHAPTER 4

Multidisciplinary Collaboration, Team Functioning, and Communication in Congenital Cardiac Care

Introduction

Texas Children’s Heart Center multidisciplinary approach

Heart Center leadership structure

Heart Center executive committee members:

Multidisciplinary distributive leadership teams:

Clinical decision‐making

Presurgical planning conference

New patient case conferences

Morning report

Data, validation, and consistency in clinical decision‐making

Multidisciplinary Surgical Patient ICU Rounds

Heart Center Quality Improvement Conferences

Performance Rounds

Heart Center Quality Conference

Multidisciplinary meeting

Heart Center Wide Communication Activities

Heart Center Town Hall

Heart Center annual retreat

Anesthesiologist involvement in patient care and leadership activities

Communication and team functioning in periprocedural areas: surgery and catheterization laboratory

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree