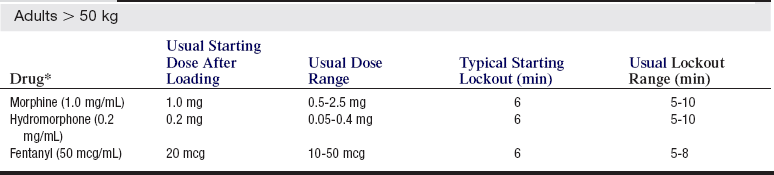

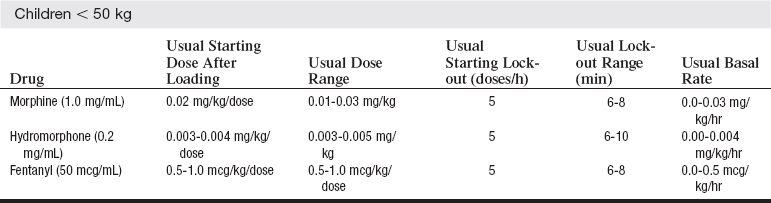

PROCEDURE 102 • Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience that arises from actual or potential tissue damage or is described in terms of such damage.1 According to the National Institutes of Health, more Americans are affected by pain than by diabetes, heart disease, and cancer combined.28 • The most common reason for unrelieved pain in hospitals is the failure of staff to routinely and adequately assess pain and pain relief.1 • Additional perceived barriers to adequate pain management are poor pain assessment, patient reluctance to report pain and take analgesics, and physician reluctance to prescribe opioids.1 Tables 102-1 and 102-2 list guidelines for dosing and considerations for selection of opioids. Table 102-1 *Typical concentrations are listed in parentheses. (Miaskowski C, Blair M, Chou R, et al: Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain, ed 6, Glenview, IL, 2008, American Pain Society, 42). Table 102-2 Patient Controlled Analgesia: Considerations in Opioid Selection (Institute for Safe Medication Practices: Patient-controlled analgesia: making it safer for patients, Horsham, PA, 2006, Institute for Safe Medication Practices.) • Unrelieved postoperative pain may result in clinical and psychologic changes, an increase in morbidity and mortality, an increase in costs, and a decrease in quality of life. Negative clinical outcomes related to ineffective pain management for patients after surgery include deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, coronary ischemia, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, poor wound healing, impairment of the immune system, insomnia, and negative emotions.25 Unrelieved pain may delay recovery and prolong hospital stays.1,3 • The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) urges healthcare professionals to accept the patient’s self-report as “the single most reliable indicator of the existence and intensity” of pain.1 • Studies and meta-analyses have shown an increase in patient satisfaction with pain management and an improvement in pain control.5,18,23,34,38 Intravenous (IV) patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) may be used for both acute and chronic pain.26 • Intravenous PCA can be an effective method of pain relief for pediatric and adult patients.14,18,34,38 Table 102-1 lists dosing guidelines. • Intravenous PCA can be administered as a continuous (basal) infusion along with patient-initiated boluses or as intermittent patient-initiated boluses exclusively. • Patient assessment at frequent, regular intervals (at least every 4 hours) should include an evaluation of the patient’s vital signs, sedation level with a valid and reliable scale, pain level with a valid and reliable scale, and common opioid side effects, such as pruritus, nausea,9,12 constipation, and urinary retention.13 Table 102-2 lists side effects associated with PCA opioids. Patients need more frequent assessments during the first 24 hours after initiation of IV PCA and during the night.10,11,14,19 Systematic evaluation of agitation and pain can lead to a reduction in pain levels and agitation.9 • PCA pump settings should be confirmed at regular intervals.10,11,19 See Box 102-1 for common terms used when administering patient-controlled analgesia. Adverse events during IV PCA may include respiratory depression and hypoxemia. Opioid anatagonists should be readily available. • Adjunctive medications can be used to improve pain management7,14,15,27,39 or to improve opioid side effects.7,15,23,24 • The Joint Commission does not support PCA by proxy (someone other than the patient pushing the PCA button) on the recommendation of the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). According to ISMP, patients have experienced oversedation, increased respiratory depression, and death from PCA by proxy.11,19,21 • PCA by authorized user (typically nurse or designated family member of patient) is a potential alternative to PCA by proxy. Healthcare institutions that use PCA by authorized user need to have the following in place before this practice is initiated.2,11,19,21,22,37,41 • Patients with an increased risk for complications during IV PCA use include those with: • Careful patient selection is imperative for effective pain management. Patients who may be poor candidates for PCA include the following:

Patient-Controlled Analgesia

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

Policies that guide the practice, including the patient population

Policies that guide the practice, including the patient population

Definition of PCA by an authorized user

Definition of PCA by an authorized user

Education plan for the authorized user

Education plan for the authorized user

Age more than 65 years (greater incidence of desaturation)29

Age more than 65 years (greater incidence of desaturation)29

Morbid obesity (greater incidence of desaturation)8,29,36

Morbid obesity (greater incidence of desaturation)8,29,36

Sleep apnea or asthma8,11,20,36

Sleep apnea or asthma8,11,20,36

Concurrent medications that potentiate opiates (e.g., sedation)11,19

Concurrent medications that potentiate opiates (e.g., sedation)11,19

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

102: Patient-Controlled Analgesia