NECK MASS

CARLA M. PRUDEN, MD, MPH AND CONSTANCE M. MCANENEY, MD, MS

Neck masses are a common concern in the pediatric population. By definition, these include any visible swelling that disturbs the normal contour of the neck between the shoulder and the angle of the jaw. The patient’s age and the location of the neck mass are important in determining the differential diagnosis. Four basic classifications of neck lesions are inflammatory, congenital, traumatic, and neoplastic. Inflammatory masses representing infectious changes in otherwise normal structures, such as lymphadenopathy and lymphadenitis, are the most common. Congenital anatomic defects of the neck including cystic hygromas, branchial cleft cysts, hemangiomas, thyroglossal duct cysts, and dermoids, may be minimally apparent, at birth, with progressive cyst formation over time. Traumatic hematomas surrounding vital structures may lead to significant distress. Malignant lesions of the head and neck are fairly uncommon, but must be ruled out, and often involve the lymphatic system. With multiple etiologies, an organized approach to the history and physical examination of the head and neck, including a working understanding of the embryology, is important to facilitate proper diagnosis and treatment.

Many factors, ranging from aesthetics to concern for malignancy may precipitate the initial emergency department (ED) visit. Direct compression of vital structures (airway, cardiovascular structures, or cervical spinal cord) can cause a principal threat to life. Rarely, systemic toxicity from progression of local infection or thyroid storm can cause uncompensated shock. In this chapter, recognition of masses that represent true emergencies will be addressed first (Table 43.1), followed by the approach to common, nonemergent lesions (Table 43.2). Table 43.3 lists causes of neck masses of children by location.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

Initial history and physical examination should rapidly assess immediate threats to airway, breathing, circulation, and neurologic status. Stridor, hoarseness, dysphagia, and drooling are ominous indications of airway compromise. Respiratory or cardiovascular compromise may manifest as mental status changes. Suspicion for traumatic injury warrants cervical spine immobilization. Table 43.1 lists disorders that constitute true emergencies because of local pressure on vital structures or because of systemic toxicity.

Child with Neck Mass and Respiratory Distress or Systemic Toxicity

Mechanism and duration of symptoms are crucial elements in the evaluation of a neck mass. Trauma from vehicular collisions, falls from heights, or sports injuries may cause hematoma formation near vital structures such as the carotid artery or trachea. If the trauma involves the cervical spine, a hematoma may occur over fractured vertebrae. Underlying coagulopathy can cause severe hemorrhage and compressive injury from hematoma, even with mild mechanisms of trauma. A high index of suspicion for bleeding disorders and nonaccidental trauma is necessary in these cases. Symptomatic arteriovenous fistulas may have a delayed presentation—up to weeks following the inciting neck trauma. Acute thoracic trauma or airway obstruction can cause increased transpulmonary pressure. The resulting air leak may dissect into the neck from the mediastinum or pleural spaces. Observation is warranted in a child presenting with crepitant neck swelling and tachypnea, as this may represent progression of a pneumomediastinum to pneumothorax. Allergic reactions ranging from local bee stings to anaphylaxis may precipitate an acute emergency if there is enough tissue edema to obstruct the trachea.

Local and regional infections may present with cervical lymphadenopathy, but can have more significant life-threatening aspects. Acute airway obstruction may result from viral or bacterial infections with associated tonsillar hypertrophy or laryngocele enlargement. Bacterial pharyngitis occasionally progresses to deep space neck infections including, retropharyngeal, lateral pharyngeal, and peritonsillar abscesses (PTAs). Lemierre syndrome, an uncommon parapharyngeal infection involving thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein with metastatic pulmonary abscesses, may manifest as respiratory distress and systemic toxicity in the adolescent with a history of pharyngitis. Dental infection that spreads to the floor of the mouth (Ludwig angina) and neck may cause neck masses and airway compression. Rarely, epiglottitis may present with associated cervical adenitis or the appearance of submandibular mass from ballooning of the hypopharynx. Concomitant dysphagia, drooling, and stridor would raise suspicion for these complications. Occasionally, branchial cleft cysts or cystic hygromas can become infected and progress to abscess formation or rarely to mediastinitis. More recently, children with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (see Chapter 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies) are reported to have parotitis or generalized lymphadenopathy (axillary, cervical, occipital), particularly visible in the neck as a presenting complaint. Children may have hyperthyroid symptoms when a neck mass represents thyromegaly. Similarly, patients with the mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki disease) often have cervical lymphadenopathy and, on rare occasions, have active life-threatening vasculitis of the coronary vessels.

Although neck tumors generally grow outward, in children, they may become large enough to encroach on vital structures. Lymphoma, an uncommon but important cause of neck mass, is usually associated with painless enlargement (often of supraclavicular nodes) that occurs over several weeks in the older school-age child. Anterior mediastinal node involvement creates airway collapse in the supine position secondary to tracheal compression. This may manifest as orthopnea. Cystic hygromas and hemangiomas occasionally enlarge sufficiently enough to interfere with feeding or to obstruct the airway. Other neoplasms, such as rhabdomyosarcoma, leukemia, neuroblastoma, and histiocytosis X, are life-threatening because of local invasion and metabolic and hematologic effects.

TABLE 43.1

LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES OF NECK MASS

Child with Neck Mass and No Distress

Most children in the ED with a neck mass are not in distress; the leading diagnoses are reactive adenopathy or acute lymphadenitis from viral or bacterial infection. A common concern, however, is deciding which neck mass bears the diagnosis of malignancy and requires biopsy or further evaluation.

History

Age at presentation of the mass aids in narrowing the diagnosis. Congenital lesions often present in infancy, though not all masses are present within the first few months of life. A neck mass presenting at several weeks of life may represent birth trauma with hemorrhage into the sternocleidomastoid and resulting torticollis. Congenital cysts, however, may not come to attention until they have become recurrent secondary to repeated enlargement with infection or inflammation. A description of the mass, noting location, size and shape, is essential, as well as any changes in its nature over time. Recent trauma from animal scratches or bites can contribute to the differential diagnosis. Dimples, sinuses, drainage, and temporal exposure to known sick contacts may suggest infectious etiology.

TABLE 43.2

COMMON CAUSES OF NECK MASS

TABLE 43.3

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF NECK MASS BY ETIOLOGY

FIGURE 43.1 Evaluation of the child with a neck mass. aMalignancy: nontender, >3 cm diameter (and firm), enlarging mass of several weeks’ duration, ulceration, location deep to superficial fascia or fixed to tissue, supraclavicular mass, systemic lymphadenopathy and bruising, superior vena cava syndrome.

In addition to establishing the duration of symptoms, it is important to ascertain the involvement of other organ systems. It is likewise important to elicit ENT and respiratory symptoms such as noisy breathing (wheezing or stridor), difficulty breathing, sore throat, and neck pain. History of fever, fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, or adenopathy elsewhere, can often suggest a diagnosis. Exposures to antibiotics or antiepileptic drugs may cause symptoms like serum sickness (fever, malaise, rash, arthralgias, nephritis) or pseudolymphoma, respectively (see Fig. 43.1).

Physical Examination

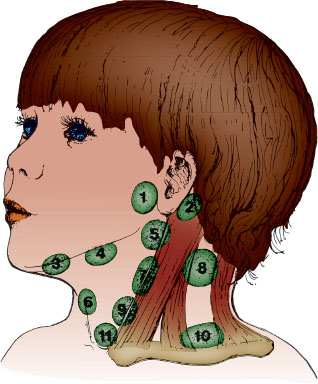

The child presenting with a neck mass should have a thorough head to toe examination, beginning with assessment for critical illness. It can be valuable to defer a meticulous neck evaluation until after completion of the remaining examination. Palpation will reveal the mass location, size, and shape. Presence of crepitation, thrill, bruit, fluctuance, or overlying skin changes should be noted. Normality of remaining structures should be ascertained to determine if additional lesions are present. Neck flexion and extension should be evaluated. Figure 43.2 diagrams common locations of neck mass. Inspection of the oral cavity should describe structures such as oral mucosa, dentition, Stensen duct (parotid gland), and other glands. Movement of the mass with swallowing or tongue protrusion is important to note. Completion of the head examination should include assessment of the scalp, ears, sinuses, and nasopharynx.

FIGURE 43.2 Differential diagnosis of neck mass by location. Area 1. Parotid: Cystic hygroma, hemangioma, lymphadenitis, parotitis, Sjögren and Caffey–Silverman syndrome, lymphoma. Area 2. Postauricular: Lymphadenitis, branchial cleft cyst (1st), squamous epithelial cyst. Area 3. Submental: Lymphadenitis, cystic hygroma, sialadenitis, tumor, cystic fibrosis. Area 4. Submandibular: Lymphadenitis, cystic hygroma, sialadenitis, tumor, cystic fibrosis. Area 5. Jugulodigastric: Lymphadenitis, squamous epithelial cyst, branchial cleft cyst (1st), parotid tumor, normal—transverse process C2, styloid process. Area 6. Midline neck: Lymphadenitis, thyroglossal duct cyst, dermoid, laryngocele, normal—hyoid, thyroid. Area 7. Sternocleidomastoid (anterior): Lymphadenitis, branchial cleft cyst (2nd, 3rd), pilomatrixoma, rare tumors. Area 8. Spinal accessory: Lymphadenitis, lymphoma, metastasis (from nasopharynx). Area 9. Paratracheal:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree