Wound Care

19-1 Cellulitis

Jay Itzkowitz

Clinical Presentation

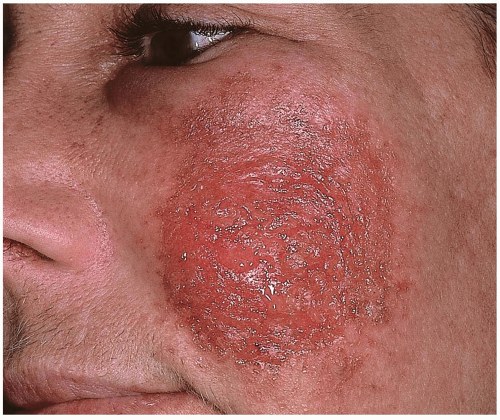

Patients with cellulitis present with a painful, indurated area of subcutaneous/cutaneous tissue with warm and erythematous overlying skin that may be smooth or even shiny in appearance.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, chills, malaise, and headache may be present. If medical care is delayed, the infection may spread in the subcutaneous tissue, resulting in erythematous streaks radiating from the primary lesion.1,2 Lymphadenitis or lymphadenopathy may be present.1

Pathophysiology

Staphylococcus aureus and group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus species are the two most common causative pathogens.1,2 In the prevaccine era, Haemophilus influenzae was also routinely seen. Cellulitis usually results from local wound infection, but it may also originate from extension of underlying infections or hematogenous seeding from a distant source.1 The primary lesion may be a puncture wound, laceration, abrasion, or insect bite, and it still may be visible at presentation.

Diagnosis

Cellulitis is a clinical diagnosis. Identification of causative organisms by Gram staining or wound cultures may prove helpful for cases in which unusual microbes are suspected (e.g., immunocompromised patient, inadequate therapeutic response despite antibiotic therapy).1 If systemic symptoms are present, blood cultures may also be positive. Laboratory testing may reveal an elevated white blood cell count. Radiographs of the area should be taken if there is a possibility of an underlying foreign body, fracture, suspicion of subcutaneous gas, or osteomyelitis.

Clinical Complications

Complications include local abscess formation, osteomyelitis, and gangrene. If left untreated, cellulitis may lead to sepsis or even death.2

Management

Patients who have no systemic symptoms may be treated on an outpatient basis, with the local application of moist, warm compresses every 2 hours for 10 to 15 minutes each time. Oral antibiotics may be appropriate in some cases, depending on the source of the cellulitis (e.g., cat bite), the location of the cellulitis (e.g., the area of the face draining to the cavernous sinus), and the patient’s underlying medical condition (e.g., immunocompromised, diabetes mellitus).1 Patients with signs of systemic toxicity or immunocompromise should be admitted for parenteral antibiotics. The antibiotics chosen should include empiric coverage against S. aureus and Streptococcus.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Bhumbra NA, McCullough SG. Skin and subcutaneous infections. Prim Care 2003;30:1-24.

2. Sadick NS. Current aspects of bacterial infections of the skin. Dermatol Clin 1997;15:341-349.

19-2 Surgical Wound Dehiscence

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Patients with surgical wound dehiscence (SWD) may present to the emergency department (ED) after surgery with overly aggressive discharge from the hospital or after outpatient surgical procedures.1,2 Superficial fascial dehiscence of abdominal incisions usually occurs early in the postoperative period, typically between days 3 and 7. However, patients may not recognize that separation of their wound has occurred until much later. Deep abdominal dehiscence may go unrecognized by the patient until increasing pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, or signs of local or systemic infection develop.1,2

Pathophysiology

Superficial wound separation usually reflects the formation of subcutaneous hematoma or seroma accumulation, as well as the development of local wound infection. True wound dehiscence involves postoperative separation of the abdominal muscular-aponeurotic layers.2 Deep dehiscence occurs less frequently than superficial separations, but it is associated with death rates as high as 24%.1 The type of incision (transverse versus midline) does not seem to influence the rate of dehiscence.2

Diagnosis

SWD usually is easily diagnosed, based on direct examination. The most frequent signs of SWD are evident in the first 72 hours after surgery and manifest with the development of serous discharge from the wound with a surrounding area of redness and tenderness.2 Leakage of peritoneal fluid or a purulent discharge from the wound are signs of possible impending dehiscence.2

Clinical Complications

Management

The operating surgeon or a surrogate should be notified as soon as possible once the stability of the patient is ensured. Most patients require hospitalization, because delayed reclosure of the disrupted wound is the preferred approach for patients with SWD.2 In the ED, SWDs should be cleansed and covered with a moist sterile dressing. Antibiotics should be administered in the ED, in consultation with the admitting surgeon.

REFERENCES

1. Madsen G, Fischer L, Wara P. Burst abdomen: clinical features and factors influence mortality. Dan Med Bull 1992;39:183-185.

2. Cliby WA. Abdominal incision wound breakdown. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2002;45:507-517.

19-3 Human Bites

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Patients with human bites present with obvious injury inflicted by a bite. Patients may withhold the cause of the injury if the bite wound resulted from a fight, domestic abuse, or criminal activity. Patients who have been bitten may not present acutely because of embarrassment or because of possible legal or criminal implications. Patients who delay seeking medical care may present with clinical complications. Bite wounds to pediatric patients may be indicative of child abuse.

Pathophysiology

Human bites are extraordinarily common, with a reported incidence as high as 1 human bite for every 600 pediatric emergency department visits.1 Males are usually bitten on the hand, arm, or shoulder, whereas females are most frequently bitten on the breast, genitalia, leg, or arm.1 The reported rate of infection for human bites varies widely. However, human bites reportedly have a higher incidence of infection than do dog or cat bites.1 Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species are the most common organisms cultured from humanbite wound infections. Anaerobes including Eikenella, Serratia, Proteus, and Enterobacter are not uncommon. Clenched-fist injuries (“fight bites”) are especially prone to infection.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on history and physical examination.

Clinical Complications

Complications may be the presenting complaint and may include deep structure injury (nerve, vessels, tendons, joints), retained teeth in the wound, spread of infectious diseases (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B or C, herpes simplex, tuberculosis, tetanus, syphilis), cellulitis, lymphangitis, abscess, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and tenosynovitis.1,2

Management

Careful examination to rule out deep structure injuries is essential. Wounds should be infiltrated with local anesthetic, then scrubbed vigorously and irrigated copiously. Some wounds require surgical exploration to determine deep structure injury or retained foreign bodies. Some wounds require soft-tissue radiographic evaluation to rule out fracture or retained foreign body. Bite wounds of the hand and other sites require splinting in plaster or bulky dressings and strict elevation. Patients with probable joint violation or deep structure violation should be hospitalized and hand/plastic surgery consulted. Prophylactic antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis should be considered in all cases. Delayed primary closure is preferred to primary closure for most bites. However, primary closure may be appropriate for some facial wounds.

REFERENCES

1. Pretty IA, Anderson GS, Sweet DJ. Human bites and the risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1999;20:232-239.

2. Wenert P, Heiss J, Rinecker H, Sing A. A human bite. Lancet 1999; 354:572.

19-4 Dog and Cat Bites

Christy Salvaggio

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

Cats inflict puncture wounds from long, thin teeth that are capable of injecting bacteria deeply into tissues or joint spaces. Dogs have broader teeth that tend to rip and crush tissue more extensively.2 These infections are commonly polymicrobial and include Pasteurella species, staphylococci, streptococci, Moraxella, Corynebacterium, and Neisseria.1

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by history and physical examination. Signs of wound infection may develop within 12 hours for cat bites and 24 hours for dog bites.1 Infection may develop in 1% to 30% of patients with dog bites and 25% to 50% of those with cat bites.2 Wound infections typically produce erythema, edema, warmth, pain, and tenderness.

Clinical Complications

Complications of bites include damage to underlying structures, infection, local abscess, lymphangitis, lymphadenitis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, tenosynovitis, and systemic infection. In unusual circumstances, if vital anatomic structures have been violated, substantial disability and even death may result.

Management

Lacerations should be copiously irrigated. Wounds with extensive tissue damage and those with joint or tendon involvement may warrant more extensive intraoperative irrigation and débridement.2 Primary closure of bite wounds predisposes to infection. However, primary closure may be appropriate for some facial lacerations. All bite wounds should be elevated and, if on an extremity, splinted. The role of prophylactic antibiotics in dog bites is controversial. High-risk patients (e.g., immunocompromised patients, diabetics, transplant recipients), wounds in high-risk regions (e.g., hand, foot, perineum), and wounds with extensive tissue damage warrant a 3- to 5-day course of antibiotics, such as empiric amoxicillin/clavulanate or penicillin with cephazolin, or clindamycin with ciprofloxacin.1,2 A lower threshold for prophylaxis applies to cat bites, given their higher infection rate. Follow-up within 24 to 48 hours is essential. The need for tetanus and/or rabies prophylaxis must be addressed.

Gram stain and culture (aerobic and anaerobic) results should be obtained if appropriate, and treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate initiated. Patients with lymphangitis, joint or tendon involvement, or systemic signs of infection should be hospitalized for intravenous antibiotic therapy, the first dose of which should be administered in the emergency department.

REFERENCES

1. Talan DA, Citron DM, Abrahamian FM, et al. Bacteriologic analysis of infected dog and cat bites. N Engl J Med 1999;340:85-92.

2. Capellan O, Hollander JE. Management of lacerations in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2003;21:205-231.

19-5 Lymphangitis

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

Group A β-hemolytic streptococcal organisms (GABHS) are common causes of lymphangitis. These bacteria produce various fibrinolysins, as well as hyaluronidase. These chemicals facilitate the invasion of lymphatic channels and consequent rapid spread of infection. Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas species, Pasteurella multocida, and Streptococcus pneumoniae may also be causative in some cases. In immunocompromised persons, gram-negative organisms of fungal species may cause cellulitis and resultant lymphangitis.1,2 The most common cause for lymphangitis, on an international basis, is Wuchereria bancrofti, a microfilarial parasitic infection. Pediatric patients who are immunocompromised, diabetic, or receiving chronic steroid therapy may be at increased risk for the development of fulminant lymphangitis.1,2

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on clinical findings, including erythematous linear streaks extending from a local skin infection or wound site toward regional lymph nodes. Tender local lymphadenopathy is common.

Clinical Complications

Management

Pediatric patients who have responsible guardians and are older than 3 years of age, afebrile, and well hydrated may be successfully treated with oral antibiotic therapy as outpatients. However, careful follow-up is essential. Parenteral antibiotics and hospitalization may be indicated in cases in which patients appear ill with signs of systemic illness, or if GABHS infection is suspected. Pain control, local splinting, elevation, and the application of warm, moist compresses every 2 to 3 hours for 15 minutes are all essential.

REFERENCES

1. Brook I. Microbiology and management of human and animal bite wound infections. Prim Care 2003;30:25-39.

2. Ben-Amitai D, Ashkenazi S. Common bacterial skin infections in childhood. Pediatr Ann 1993;22:225-227, 231-233.

19-6 Puncture Wounds

Sarah Jane Paris

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

Puncture wounds (PWs) are wounds with vector forces or partial forces directed to the surface of the skin at any angle. Patient presentation depends on the nature, direction, and degree of these forces. Special consideration should be given to puncture wounds that are likely to be associated with retained foreign bodies in deep soft tissue. Any PW involving the plantar surface of the foot, especially one that occurs through footwear, is at high risk for infection. Pseudomonas infections have been reported when PWs occur through tennis shoes.2 Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis, in addition to Streptococcus species, are also common infecting organisms.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on history and physical examination. Radiographs may help detect foreign bodies or bony injury and should be performed even if radiolucent objects are not suspected.1,2

Clinical Complications

Management

Careful examination to rule out deep structure injuries is essential. Wounds should be infiltrated with local anesthetic and then scrubbed vigorously, irrigated copiously, and débrided of devitalized tissue. Some wounds require surgical exploration to determine deep structure injury or retained foreign bodies. Radiographic imaging is required for all infected PWs and whenever there is a suspicion of retained foreign bodies.1 PWs involving the hand and other locations require splinting in plaster or bulky dressings and strict elevation. Patents with probable joint violation or deep structure violation should be hospitalized and hand/plastic surgery consulted. Prophylactic antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis should be considered in all cases, but extensive evidence of efficacy is lacking. Antibiotics are not a substitute for meticulous wound care.1 Primary closure is not indicated for any PW, because it can be expected to facilitate the development of infection. Probing and “grabbing” for unseen foreign bodies is unwise, because objects may be forced into deeper tissue.1 Tetanus immunization should be updated.

REFERENCES

1. Brook JW. Management of pedal puncture wounds. J Foot Ankle Surg 1994;33:463-466.

2. Graham BS, Gregory DW. Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing osteomyelitis after puncture wounds of the foot. South Med J 1984;77:1228-1230.

3. Pennycook A, Makower R, O’Donnell AM. Puncture wounds of the foot: can infective complications be avoided? J R Soc Med 1994; 87:581-583.

19-7 Wound Retained Foreign Bodies

James Nelson

Colleen Campbell

Clinical Presentation

In acute soft-tissue injury, retained foreign bodies (RFBs) may not produce specific symptoms or signs. Some patients complain of a sharp pain on palpation directly over a puncture wound, and some subcutaneous RFBs may be palpable.1 Older RFBs may manifest as nonhealing wounds, cellulitis, abscess, granuloma, or osteomyelitis.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree