Chapter 17 Workplace Safety Issues and Trends

Promoting patient safety has always been a fundamental philosophy for the profession of nursing. However, it has not been until the past decade that nurses have voiced their concerns related to issues affecting nurses—specifically, workplace safety issues. Many workplace safety issues that directly affect the nurse also have an indirect effect on patient safety, and the two should never be addressed in isolation from one another (Aiken et al, 2002; Needleman et al, 2002). Nurses today routinely deal with critical issues related to the provision of safe patient care; however, they often do not pay attention to their own workplace safety issues (Foley, 2004).

WORKPLACE SAFETY ISSUES

As a professional group, nurses are extremely dedicated, and most will always place patient needs first. As an example, nurses often volunteer to work extra shifts to provide adequate coverage for patients. The perioperative nurse will decline break and lunch relief when it is not in the best interest of the patient to depart from the case (e.g., critical time of cross clamping of the aorta). Perioperative nurses are required to stand for prolonged periods of time and may put their bodies in awkward positions when retracting with instruments during a surgical case. Daily, perioperative nurses are required to lift heavy equipment and transfer patients, frequently with minimal assistance. Although this list of nursing actions is not intended to be exhaustive, the list demonstrates that the patient’s welfare is always placed first. Unfortunately, some of these nursing actions that are required for patient care place the nurse at an increased risk for injury (ANA, 2001b). As previously stated, it is common for nurses to overlook issues of their own well-being and safety to provide patient care. Many people may question the wisdom and the end result of this dedication.

Aging Workforce

It is projected that in 2010 40% of nurses in the United States will be older than 50 years of age (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2001). Research supports that one out of every five nurses will leave nursing prematurely for reasons other than retirement (Federation of Nurses and Health Professionals, 2001). Reasons for leaving the profession prematurely include factors such as fatigue, long work hours, stressors associated with the physical demands of the work, chronic lumbar pain, and personal injury (ANA, 2001b; Federation of Nurses and Health Professionals, 2001; U.S. General Accounting Office, 2001; Foley, 2004). Nurses who are now entering the profession appear less inclined to accept the status quo and expect that workplace issues will be addressed to adequately protect the nurse, which in return better protects the patient.

Nursing Shortage

How the recession will alter the nursing shortage remains unclear. Recent reports suggest that the nursing shortage appears to have decreased related to current economics. Many nurses have elected to delay retirement, resulting in fewer hospital vacancies for the registered nurse (RN) (Calvan, 2009). Despite the fact that there a fewer nursing vacancies, Buerhaus et al (2009) project a shortage of 260,000 RNs by 2025. This is attributed to the aging workforce.

The nursing shortage is not limited to the United States. The International Council of Nurses (ICN) (2006) recognizes a worldwide nursing shortage affecting developing and developed countries. Action plans are similar to those of the United States, with recommendations to address the practice environment for nursing (ICN, 2006).

In 2009 the Canadian Nursing Association recommended addressing environmental issues to decrease absenteeism for Canadian nurses, which is likely an outcome attributed to fatigue and workplace issues (Kyle, 2009). It is also being realized in the United States that workplace issues must be addressed to effectively recruit and retain nurses (Foley, 2004).

Work-Related Injuries

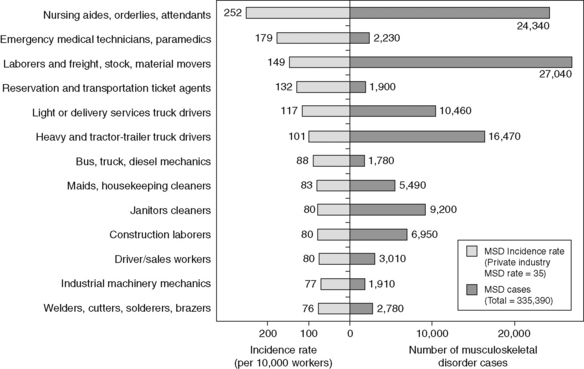

Nursing ranks among one of the highest professions for work-related injuries. Data on nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work collected by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2008) from 2006 to 2007 identifies the occupation group of RNs as the tenth-highest occupation for work-related injuries. A subset of the nursing group identified as nursing aides, orderlies, and attendants is the third-highest injured group, falling just below the occupations of truck drivers (heavy and tractor-trailer), laborers, and material movers. Data collected from 2006 to 2007 reported a total of 64,950 work days for nursing personnel that were lost because of work-related injuries. The total for nursing aides, orderlies, and attendants was 44,930 days and for RNs, 20,020 days. The highest rate of injuries and illness in nursing occurs with the subset of nursing aides, orderlies, and attendants. The most frequent work-related injury is a musculoskeletal disorder, which occurs more frequently for this subset than for laborers, freight handlers, and delivery truck drivers (Figure 17-1).

(Modified from Bureau of Labor Statistics: Nonfatal occupational injuries and illness requiring days away from work, Washington, DC, November, 20, 2008, U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, available at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh2.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2009.)

Personal Health and Safety

Today more nurses are cognizant of their personal health risk and are no longer “accepting” the idea of taking risks for personal injury or untoward health effects when there are preventive measures such as equipment that will minimize the risk for the nurse (e.g., smoke evacuation). In 2001 the American Nurses Association (ANA) (2001a) conducted a Health and Safety Survey to evaluate exposure to hazards in the workplace for registered nurses. Across the United States 4826 nurses participated in the survey to report health and safety concerns. Of these nurses, 60% expressed concern related to on-the-job disability resulting from a back injury, 45% were concerned about needlestick injuries and contracting a bloodborne pathogen, and 21% were concerned about developing latex allergies. Health care facilities are becoming more aware of the importance of addressing nursing issues, ensuring that every nurse feels safe, and supplying the necessary equipment and staffing to provide safe patient care. Nursing professionals are becoming more astute and understand that patient safety advocacy begins with advocacy for a safe workplace environment for the nursing staff. Mary Foley, past ANA president, states, “Nurses shouldn’t fear for their own health and safety when they go to work” (Medscape Medical News, 2001).

AORN POSITION STATEMENT ON WORKPLACE SAFETY

Biologic Risk

The first category of workplace exposure is biologic risk, which includes exposure to bloodborne pathogens, infectious agents, biologic components of surgical smoke, and allergens contained in latex products such as surgical gloves. The bloodborne pathogens’ risks to health care workers were known for decades. However, no risk-reduction efforts or concerns were set forth until the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was described in 1981 (Berguer and Heller, 2004). Currently the pathogens of greatest concern are HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2003). In 1987 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 1987) released the universal precautions for use on every patient, by all persons, all of the time.

The complex issues related to bloodborne pathogen exposures, especially in the operating room environment with needlestick injuries and other sharps-related injuries, continue to be a potential hazard. In 1991 the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued the bloodborne pathogens standard (29 CFR 1910.1030) designed to protect health care workers at risk. The bloodborne pathogens standard has undergone revision based on new evidence for prevention and is expected to be implemented by each facility. The bloodborne pathogens standard required facilities to implement an exposure-control plan, compliance with the universal precautions, engineering controls, barrier protection, free HBV vaccinations, education and training programs, and postexposure evaluation (OSHA, 1991). This is enforced through the OSH Act of 1970, often referred to as the General Duty Clause (OSHA, 1970):

Even with the CDC’s recommended standard precautions and the regulation behind the OSHA’s bloodborne pathogens standard to decrease risk, the risk in the operating room remains evident. Quebbeman et al (1991) report that untoward outcomes for staff include cuts or needlestick injuries in approximately 15% of operations studied. Gerberding et al (1990) report accidental exposure (parenteral or cutaneous) of 6.4%. If study results are applied across the more than 50 million surgical procedures performed annually in the United States, the adequacy of protection for health care personnel in the operating room environment must be questioned. Many suggest that even with the application of standard precautions and the OSHA bloodborne pathogens standard there remains the inability to fully understand and address the many issues surrounding bloodborne pathogen exposure in the complex operating room environment (Berguer and Heller, 2004). Chapter 19 reviews the issues and recommendations for prevention of sharps injuries in the operating room.

Ergonomics

The second category of workplace safety exposure is ergonomics. This includes static or awkward positions, standing for prolonged periods of time, back injuries, repetitive motion, lifting of heavy patients, and transportation of heavy equipment (AORN, 2006). Perioperative scrub persons and first assistants are frequently required to stand in awkward positions at the surgical field. It is not unusual to remain in an awkward position (e.g., holding instruments) for prolonged periods of time. Staff members who are “scrubbed in” on long cases and relieved by someone else only for mandatory breaks and lunch may complain of lumbar strain, aches, discomfort, and extreme muscle fatigue.

In addition to the above workplace ergonomics, there are issues related to patient transfer, patient positioning, holding extremities for the surgical preparation, and transferring the patient following surgery. The trend of implementing lift teams and using special equipment for moving and positioning patients has been minimally implemented in the surgical services area. Chapter 21 reviews the issues and challenges of preventing back injuries in the perioperative staff, with emphasis on the unique job requirements of the operating room.

Chemical Exposure

The third category of workplace safety exposure is chemical and associated with anesthesia gases, disinfecting/sterilizing agents, cleaning agents, and specimen preservatives (AORN, 2003). There is long-standing concern related to exposure to waste anesthetic gases and the potential for negative effects on health care workers. Waste anesthetic gases expose health care workers to volatile gases, generally in small amounts, as a result of leakage from the anesthesia breathing circuit into the operating room air (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH], 2007). Waste anesthetic gas exposure may include exposure to halothane, enflurane, isoflurane, desflurane, sevoflurane, and nitrous oxide. There are studies that demonstrate adverse health effects from chronic exposure. Some studies link exposure to the occurrence of miscarriages, genetic disorders, and cancer (NIOSH, 2007).

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (2007) recommends that health care facilities develop a hazard communication program that includes a safety plan related to exposure, methods to minimize and control exposure, labeling of cylinders with anesthetic agents, availability of material safety data sheets (MSDSs), provision of training and education for health care workers as required by the OSHA hazard communication standard (20 CFR 1910.1200), and installation of a waste scavenging system to remove anesthetic gases in the perioperative area.

NIOSH recommends specific ventilation exchanges to minimize exposure to waste anesthetic gases that are routinely exhaled by the patient. NIOSH (2007) recommendations include a facility ventilation system for the operating room that should provide 15 air exchanges per hour, with a minimum of 3 air changes of fresh air hourly. The ventilation system for the postanesthesia recovery area should provide at least 6 air changes per hour, with at least 2 air changes of fresh air hourly (NIOSH, 2007).

The anesthetic equipment should be maintained, including the breathing circuits and the waste-gas scavenging systems. Staff should be educated and trained in awareness, prevention, and control recommendations related to minimizing exposure to waste anesthetic gases. Recommendations from NIOSH (2007) for operating room personnel and anesthesia providers include the following:

• Periodically monitor staff liver and kidney function.

• Monitor pregnancy outcomes for female workers and wives of male workers.

• Inspect anesthesia delivery system for any interruptions.

• Confirm that the ventilation system is working properly.

• Confirm that the waste scavenging system has been properly applied and is working correctly.

• Gas flow should be activated after the delivery system is connected to the laryngeal mask or endotracheal tube.

• Vaporizers should be filled using a ceiling-mounted hood with working evacuation system.

• Vaporizers should not be filled during delivery of anesthesia.

• Uncuffed endotracheal tube should have a completely sealed airway.

• Administer the lowest possible anesthetic gas flow rate.

• Avoid high anesthetic gas flow rates.

• Avoid anesthesia delivery via open drop methods.

• If a mask is applied, it should fit correctly.

• Apply waste scavenging system to eliminate residual gases before disconnecting from the breathing circuit.

• Stop gases by turning the valve off before disconnecting the patient’s breathing system.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree