Chapter 2 What is the joint hypermobility syndrome?

JHS from the cradle to the grave

Introduction

What is joint hypermobility?

There is widespread misunderstanding over the use of the terms joint hypermobility (JHM) and joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS). Hypermobility implies a range of joint movement that exceeds what is considered to be normal for that joint taking into consideration the individual’s age, gender and ethnic background. It does not necessarily lead to symptoms; it is not a disease state; it is not a diagnosis. Many, if not most, hypermobile people may not even be aware that they are hypermobile. They generally assume that their range of movement represents the norm (which, of course, is not the case!). For many performing artists it acts as a positive selection factor in their successful recruitment (McCormack et al 2004).

JHM is measured by the ability to perform a number of manoeuvres. The two scales that have received greatest popularity are the Beighton 9-point scale (Beighton et al 1973) (Chapter 1, Figure 1.3), and the Rotes-Querol Scale (Bulbena et al 1992), the latter being favoured in Spanish-speaking countries. The reproducibility of the Beighton scale has recently been tested (Juul-Kristensen et al 2007) showing a higher kappa value in the Beighton tests (generally above 0.80) than in the Rotes-Querol tests (generally > 0.57). Despite the survival of these scoring systems for over three decades, and their good reproducibility, they have been subjected to criticism from clinicians for several reasons: they are ‘all or none’ tests and give no indication of the severity of JHM; the count diminishes over time and may fall to zero with ageing; injury may reduce apparent range of movement; they favour the upper as opposed to the lower limbs; and they only sample few body sites, so that JHM at other sites may be overlooked. Perhaps, the most serious accusation is that rheumatologists and others see the score as the be all and the end all of JHM and fail to seek (and hence to find) the other features of JHS (Grahame 2008).

What is the joint hypermobility syndrome?

Joint hypermobility only becomes JHS when it is deemed to be responsible for emerging symptoms, of which pain and instability are the most important. The term hypermobility syndrome (HMS) was first coined in 1976 and defined as the occurrence of musculoskeletal symptoms in the presence of joint hypermobility in healthy individuals (Kirk et al 1967). In this context, ‘healthy individuals’ should be interpreted as meaning an absence of other (inflammatory) rheumatic diseases. At the time it represented an important historical landmark, but over the last four decades burgeoning evidence has revealed overlapping features with other heritable disorders of connective tissue (HDCTs) (Chapter 1) suggesting that JHS is, itself, a forme fruste of an HDCT (Grahame et al 1981, Grahame 1999).

The Brighton Criteria for JHS

The Revised 1998 Brighton Criteria for the benign joint hypermobility syndrome, promulgated by the British Society for Rheumatology Special Interest Group on the Heritable Disorders of Connective Tissue represents a validated set of Classification Criteria for the BJHS (now generally termed JHS) (Grahame et al 2000). Like its sister sets of criteria for Marfan (De Paepe et al 1996) and Ehlers-Danlos (Beighton et al 1998) syndromes, the Brighton Criteria comprise sets of major and minor criteria (Chapter 1, Table 1.1). The criteria are met when either two major, or one major and two minor, or four minor are satisfied. Two minor criteria alone suffice in the presence of an unequivocally affected first-degree relative. Although designed primarily as a tool to identify JHS in the research setting, anecdotally they are also useful as a diagnostic aid in the clinical setting. Reproducibility of the Brighton Criteria has been found to be excellent with a kappa value above 0.73 (with the exception of the skin stretch (0.63)) (Juul-Kristensen et al 2007). It should be noted that the Brighton Criteria were conceived in the 1990s, since when there has been a veritable explosion of new information and knowledge regarding JHS. There is general consensus that the Criteria need to be regularly reviewed and updated in the light of this new knowledge (Juul-Kristensen et al 2007).

Successive studies using the Brighton Criteria have demonstrated that JHS is a multifaceted disorder that frequently affects body systems remote from the confines of the locomotor system and bearing little obvious direct relationship to it. These intriguing nuances will be revealed in the coming chapters. The stark reality is that clinicians appear by and large to be unaware of them (Grahame 2008).

Bravo in Santiago, Chile, has undertaken a detailed clinical evaluation of his patients and finds an exceptionally high prevalence of previously undiagnosed HDCTs (overwhelmingly patients with JHS) in his clinic. He advocates the use of the 1998 Brighton Criteria in preference to the 9-point Beighton score for the recognition of JHS, the latter in his series gave a 35% false-negative diagnosis rate. He draws attention to important clinical signs of JHS which have not yet received widespread recognition including blue sclera, osteopenia/osteoporosis, typical facies and the recognition of hypermobile hand postures as in the ‘hand holding the head’ sign (Bravo & Wolff 2006).

Is JHS the same as the hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome?

There has been a lively debate as to whether JHS and the hypermobility type of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (HT-EDS) (Chapter 1, Table 1.2) are one and the same or represent two phenotypically related conditions. The recently published Position Statement from the Professional Advisory Network of the Ehlers-Danlos National Foundation (of the USA) has clearly and unequivocally expressed the present consensus trend (Tinkle et al 2009). It states that ‘it is our collective opinion that BJHS/HMS and EDS hypermobility type represent the same phenotypic group of patients that can be differentiated from other HCTD but not distinguished from each other’.

Hypermobility in children

JHS is the one rheumatological disorder, par excellence, that transcends the child–adult divide. It casts its shadow across the whole age range, literally, from the cradle to the grave, as this chapter will attempt to illustrate. One’s genetic profile is established at the moment of conception. By the time of birth, one of the earliest known associations with hypermobility, namely congenital hip dysplasia, manifesting either as a ‘clicky hip’ or as a frank congenital dislocation (CDH) may already be apparent (Wynne-Davies 1971) and should always be sought in the neonatal period by careful clinical examination and, where appropriate, by ultrasound examination (Poul et al 1998). Maternal pre- and perinatal issues are covered in Chapter 12.6.

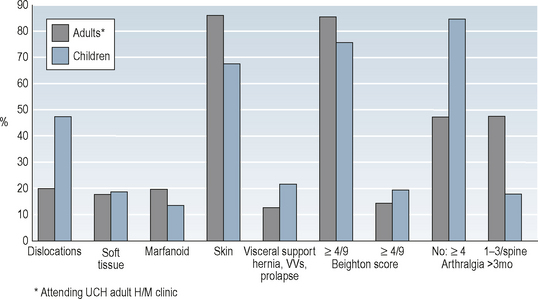

The Brighton Criteria have, strictly speaking, not yet been fully validated in children. However, their potential use in children has been explored in 36 patients clinically diagnosed as JHS aged 4–18 (median 11) years seen in the Hypermobility Clinic at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London between October 2004 and March 2006; 31/36 (86%) satisfied the Brighton Criteria for JHS giving a specificity of 86%. Sensitivity was not studied. A comparison of the performances of the individual Brighton Criteria in these children with that seen in an adult JHS cohort of 558 shows that they performed reasonably well. This is seen in Figure 2.1 (authors correspondence, unpublished data).

In the photographs a young patient is seen demonstrating her ability to perform the Beighton Score as well as the increased extensibility of her skin (Figure 2.2a–f).

A novel suggestion has been put forward recently by a paediatric group in Australia suggesting that the term JHS should be extended to include all hypermobile children with musculoskeletal symptoms irrespective of genetic cause so that potentially they may all benefit from a programme of multidisciplinary rehabilitation, as well as identifying the genetic cause of joint hypermobility (where possible). They propose the use of both diagnostic labels, i.e. JHS, and the individual’s HDCT diagnosis (Tofts et al 2009).

The clinical spectrum in children

JHM in children is common but often missed by clinicians. It is one of those conditions which ‘you see if you look for it, but not if you don’t’. Yet as has been suggested in a paper from Turkey, ‘evaluating (child) patients for hypermobility in routine rheumatologic examination will obviate the need for unnecessary diagnostic studies and treatments’ (Toker et al 2009).

Motor delay and abnormal gait

One of the most common features of JHS in early life is motor delay. It was observed in approximately one third of children with generalized JHM in one series (Engelbert et al 2005). Delay in onset of walking independently, omitting to crawl and the use of bottom-shuffling or sometimes commando crawl is seen as an alternative means of locomotion. There is often also a clumsiness of movement (that may persist into adult life), as well as an irrepressible fidgetiness in affected children. When they do start to walk, hypermobile toddlers find walking on tiptoes, or with an inward or outward toeing gait, splints the ankle. This gives them a sense of better support and so they employ an abnormal gait. However the toeing gait often leads to frequent falls as the feet trip over one another. This is often the time when parents notice easy bruising especially on the shins. Many hypermobile children have been investigated for bruising which is a common feature in this condition. Test of bleeding diatheses are almost invariably normal, and the bruising can be explained on the basis of lack of the normal capillary support afforded by the inherently weak collagen infrastructure. Once walking, parents often notice that their child has very flat, pronated feet (see later). Reassurance along the lines that all infants are like this is misleading. Flat pronated feet lead to abnormal gaits (Chapter 12.5) with features such as:

Fortunately, the motor delay diminishes as the infant develops (Davidovitch et al 1994). A recent study of 29 infants from the same group reveals that this catch-up can be helped by a programme of monthly physical therapy combined with a home treatment protocol administered by caregivers. Weekly physical therapy offered no advantage over a monthly regimen (Mintz-Itkin et al 2009).

Children with JHS often have poor ball-catching skills and difficulty with using scissors due to an associated developmental coordination disorder (dyspraxia) (Kirby & Davies 2007).

Proprioception is often poor in hypermobility persisting into adulthood (Chapter 6.4). This leads to frequent falls, and also clumsiness with walking into door frames and furniture, tripping over, and knocking objects over being common complaints. Once the infant has mastered walking other milestones such as climbing and running are difficult due to suppleness and weakness of muscles. The gait is further disrupted as in pronation the first metatarsophalangeal joint is locked and thus toeing off may be difficult if not impossible.

Much of the locomotor difficulty encountered by children with JHS derives from impairment of muscle power and proprioceptive acuity which can be detected both clinically and experimentally. In one study of 37 healthy children (mean age ± s.d. = 11.5± 2.6 years) and 29 children with JHS (mean age ± s.d. = 11.9 ± 1.8 years) the children with JHS had significantly poorer joint kinaesthaesia, joint position sense and muscle torque than that found in control subjects (both P < 0.001). Knee extensor and flexor muscle torque was also significantly reduced (both P < 0.001) in children with JHS compared with healthy counterparts. The authors concluded that these findings provided a rationale for the use of proprioceptive training and muscle strengthening in treatment (Fatoye et al 2009) as has been advocated clinically (Maillard et al 2004) (Chapter 11). A recent Dutch study demonstrated in 41 hypermobile children (mean age 9 years) that only muscle strength correlated with motor performance (Hanewinkel-van Kleef et al 2009) adding yet further weight to the primacy of muscle strength and stamina in children with JHS.

Scoliosis and JHS in children

Scoliosis is a frequently encountered finding in children and adults with JHS. A recent study of joint laxity during scoliosis screening of 1273 children (males 598; females 675; mean age 10.4 years) using the Bunnell scoliometer (Bunnell 1993) showed a correlation between the Beighton score and trunk rotation of ≥ 7° (Erkula et al 2005).

Joint pain and hypermobility in children

Paediatric rheumatologists now acknowledge that many if not most children and adolescents attending paediatric rheumatology clinics will have a non-inflammatory origin for their complaints or disorder. Mechanical causes are frequently identified, and hypermobility or ligamentous laxity of joints is increasingly recognized as an aetiological factor in the presentation (Murray 2006).

In spite of this several authorities are sceptical about the link between hypermobility and pain and doubt the existence of a causative link between JHM and musculoskeletal pain (MSKP) thereby challenging the very existence of JHS. One typical example was a recently published Italian study of 1046 schoolchildren (mean age 10.8; range 7–15 years). MSKP was found in 18%. The study group was composed of children experiencing pain once per week; 22% of children with MSKP had a Beighton Score of ≥ 5/9 compared with 23% of controls who had pain only rarely or never. Because they have only looked at the Beighton Score (rather than for JHS using the Brighton criteria), the authors have failed to distinguish between subjects with JHM and those with JHS (Leone et al 2009).

Restricting evaluation to the Beighton Score (rather than taking a broader view using the Brighton Criteria) may have led to an erroneous conclusion of no influence of JHM on the outcome of neck pain in 1756 Finnish 9–12-year-olds followed for 1–4 years. Other factors (now known to be strongly associated with JHS) such as concurrence of frequent other musculoskeletal pains, headache, abdominal pain, day tiredness, depressive mood and sleep difficulties were found to be risk factors for both the occurrence and persistence of weekly neck pain during the subsequent 4-year period (Stahl et al 2008).

By contrast, in a study of 829 Mumbai children aged 3–19 years from an urban lower socio-economic population with a high prevalence of JHM, 59% showing a Beighton score of > 4/9, 26% of the JHM children had MSKP symptoms compared with only 17.7% in the non-JHM children (P < 0.05). A striking novel finding was the higher prevalence of JHM in those with malnutrition (61.5%) compared with those with normal nutrition or mild grades of malnutrition (36.8%) (Hasija et al 2008).

Flat feet (pes planus) in children

Examining the feet barefoot (see Chapter 12.5) is an essential part of the examination of the child, and it is an obvious and easy way to spot hypermobility. It might provide the instant clue to a diagnosis of JHS. In a recent study a significant statistical correlation was found between JHM and the occurrence of both pes planus and arthralgia in pre-pubertal children (Yazgan et al 2008). An example of pes planus in JHS is seen in Figure 2.3a, b.