CHAPTER 6 Watchful Waiting and Brief Education

Description

History and Frequency of Use

Given these changes in the broad understanding of LBP, it is not surprising that the advice given to patients by health care providers about LBP has changed markedly over the years, often resulting in contradictory messages, misconception, and confusion. The application of evidence-based medicine (EBM) to the management of LBP attempted to improve and clarify this situation. In the early 1990s, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR), presently known as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), assembled a multidisciplinary group of expert clinicians and researchers to develop clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) on the management of acute LBP in adults based on the best available scientific evidence.1 It was proposed at the time that the first step in managing LBP was to conduct a basic diagnostic triage and group patients into one of three categories: (1) potentially serious spinal conditions (e.g., spinal fracture, spinal infection, spinal tumor, or cauda equina syndrome), (2) nerve root compression (e.g., sciatica, radiculopathy), and (3) nonspecific back symptoms. This triage was intended to be sequential and to unfold by process of elimination (e.g., after eliminating potentially serious spinal conditions and nerve root compression, it was assumed that the patient had nonspecific LBP). Although potentially serious spinal conditions required additional diagnostic testing, both nerve root compression and nonspecific LBP were deemed self-limiting in most cases and could improve without medical attention or with only conservative interventions. These recommendations were widely distributed in the United States, and this approach was slowly adopted by health care providers, after which watchful waiting became a more accepted option for LBP.

Traditional approaches based on the medical model of disease were contrasted with a biopsychosocial model of illness to reexamine success and failure in the management of LBP. This shift in thought regarding LBP inspired others to reconsider its management. For example, Indahl and colleagues began telling patients with LBP that light activity would not further injure their discs or other structures.2 Following a clinical examination, brief education was given by a physiatrist, physical therapist, or nurse, who instructed patients that the worst thing they could do to their back was to be too careful. Any perceived link between emotions and chronic low back pain (CLBP) was simply attributed to increased tension in the muscles. Brief education has also been managed in the physical therapy setting.3,4 Cherkin and colleagues evaluated the value of an educational booklet in patients with acute LBP, which was not effective in reducing symptoms, disability, or health care use.5 Their findings challenged the value of purely educational approaches in reducing symptoms and costs of LBP when delivered solely with a booklet.

Procedure

Watchful Waiting

Waiting

It has been observed in several reports that the vast majority of acute LBP episodes resolve spontaneously with time (Figure 6-1). A preexisting active lifestyle has been shown to accelerate symptomatic recovery and to reduce chronic disability.7 The routine use of passive treatment modalities is not recommended, because it might promote chronic pain behavior. Such interventions may be more appropriate for “subacute” pain. The British Medical Journal reported that increased stress from therapeutic exercises may be harmful in acute LBP based on a randomized clinical trial that was included in the Philadelphia Panel.8

Reassurance

Reassurance may help patients, decreasing their stress and anxiety, and thus reducing inappropriate pain behavior and encouraging proactive healthy behavior (Figure 6-2). Reassurance may be the first step of psychological treatment. Some authors recommend that in addition to the traditional examination of neurologic symptoms and signs, psychological factors should be considered at the initial visit for a patient with an episode of LBP. Reassurance usually consists of educating the patient that LBP is a common problem and that 90% of patients recover spontaneously in 4 to 6 weeks.9 Patients also need to be reassured that complete pain relief usually occurs after, rather than before, resumption of normal activities and that they may return to work before obtaining complete pain relief; working despite some residual discomfort from LBP poses no threat and will not harm them.10

Activity Modification

Although severe LBP may necessitate rest or activity modification as tolerated by each patient, mandatory bed rest has not been shown to be beneficial in the overall course of acute back pain. If disabled by pain, bed rest may be recommended, but for no more than two days, because longer periods of bed rest can delay recovery.10–12 The Philadelphia Panel found good evidence to encourage continuation of normal activities as an intervention for people with acute LBP.8 The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) also recommends that patients with acute LBP be advised to stay active and continue ordinary daily activities within the limits permitted by the pain. Patients may be advised to carefully introduce activities back into their day as they begin to recover.10 Gradual stretches and regular walking are good ways to get back into action. Patients also need to be told to relax, because tension will only make their back feel worse. Patients should also be instructed to avoid activities that caused the onset or aggravation of symptoms, especially those that peripheralize (spread outward to the extremities) symptoms.

Education

Educating patients about LBP can help them take steps in their everyday lives that will help maintain back health (Figure 6-3). Although most studies point to the spontaneous resolution of the vast majority of episodes of LBP, there exists controversy in this area. For example, ICSI provides a slightly less optimistic outlook and states that most patients will experience partial improvement in 4 to 6 weeks and will have a recurrence of LBP in 12 months.10 The long-term course of LBP typically allows for a return to previous activities, although often with some pain. Employers are encouraged to develop and make available patient education materials concerning prevention of LBP and care of the healthy back. Topics that should be included are promotion of physical activity, smoking cessation, and weight control; these interventions are reviewed in Chapter 5. Emphasis should be on patient responsibility and self-care of acute LBP. Employer groups should also make available reasonable accommodations for modified duties or activities to allow early return to work and minimize the risk of prolonged disability. Education of frontline supervisors in occupational strategies to facilitate an early return to work and to prevent prolonged disabilities is recommended.10

Brief Education

Brief education encompasses many of the elements already described and attempts to achieve the same goals as back schools in a condensed time period. Brief education often consists of a single discussion with a health care professional, including physical therapists, primary care physicians, chiropractors, or behavioral health care providers. Follow-up sessions may also be held to reinforce some of the important messages or monitor changes in clinical presentation (Figure 6-4). Alternatively, brief education may also be delivered by a trained lay person (often someone who has personally experienced CLBP), or supplemented through a brochure or book, or in a moderated online discussion group.13 Brief education often summarizes some of the basic information about LBP presented in lengthier back schools. Back schools are not standardized but generally encourage self-management using heat, ice, over-the-counter analgesics, or relaxation techniques, provide advice to remain active despite the pain, and address common misconceptions about LBP (e.g., that diagnostic imaging is always required).

Theory

Mechanism of Action

The principal mechanism of action involved in watchful waiting is allowing sufficient time for the body’s natural healing mechanisms to repair the injured tissues at the root of CLBP, whatever they may be. Watchful waiting therefore depends on what is currently known about the natural history of LBP. Epidemiologic studies of LBP indicate that it is a common but benign condition of mostly unknown etiology that generally improves within a few weeks and disappears within a few months, although periodic recurrences are expected.14 Such observations are based on population studies and cannot be extrapolated to every patient with LBP. Watchfulness is therefore necessary to identify rare but potentially serious spinal pathology that may be responsible for symptoms and may require urgent treatment. It is also important to identify rare nonspinal causes of LBP that may need to be addressed if the LBP is to improve.

Assessment

Before receiving watchful waiting or brief education, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating these interventions for CLBP.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Brief Education

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found conflicting evidence that brief education delivered through Internet-based discussion groups is more effective than no intervention with respect to improvements in pain and function.13 That CPG also found limited evidence that brief education is as effective as massage or acupuncture with respect to improvements in pain and function. That CPG also found moderate evidence that brief education combined with advice to remain active is more effective than usual care with respect to improvements in disability. That CPG also found moderate evidence that brief education encouraging self-care is more effective than usual care with respect to improvements in function, but not pain. That CPG also found strong evidence that brief education, when combined with advice to remain active, is as effective as usual physical therapy or aerobic exercise with respect to improvements in function. That CPG recommended brief education in the management of CLBP.

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found moderate evidence that brief education is effective with respect to improvements in function and disability.15 That CPG recommended brief education in the management of CLBP.

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found evidence of a moderate benefit for brief education in the management of CLBP.16

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 reported that brief education alone is not sufficient for the management of CLBP.17

Findings from the above CPGs are summarized in Table 6-1.

TABLE 6-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations About Watchful Waiting and Brief Education for Chronic Low Back Pain*

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Brief Education | ||

| 13 | Europe | Recommended for management of CLBP |

| 15 | Belgium | Recommended for management of CLBP |

| 16 | United States | Evidence of moderate benefit |

| 17 | United Kingdom | Brief education alone is not sufficient |

CLBP, chronic low back pain.

* No CPGs made recommendations about watchful waiting as an intervention for CLBP.

Systematic Reviews

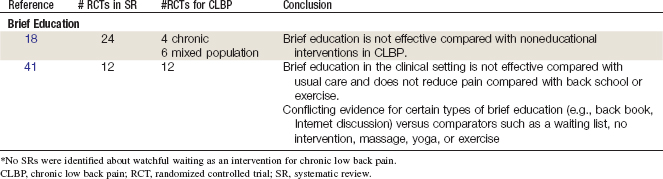

Brief Education

Cochrane Collaboration

An SR was conducted in 2008 by the Cochrane Collaboration on individual patient education for acute, subacute, and chronic nonspecific LBP.18 A total of 24 RCTs were included. Of those, 14 included acute or subacute LBP patients, 4 included CLBP patients, and 6 included a mixed population.2,19–40 This SR concluded that individual education was not effective compared with noneducational interventions for CLBP. In particular, written educational material is less effective than noneducational interventions.

Other

An SR was conducted in 2008 by Brox and colleagues on back schools, brief education, and fear avoidance training for CLBP.41 A total of 23 RCTs were included, of which 12 pertained to brief education. This SR concluded that there is strong evidence that brief education leads to reduced sick leave and short-term disability versus usual care. However, there was strong evidence that brief education in the clinical setting did not reduce pain compared with usual care and limited evidence that brief education in the clinical setting did not reduce pain compared with back school or exercise. Furthermore, this SR concluded that there is conflicting evidence for certain types of brief education (e.g., back book, Internet discussion) versus comparators such as a waiting list, no intervention, massage, yoga, or exercise.

Findings from the above SRs are summarized in Table 6-2.

Randomized Controlled Trials

Brief Education

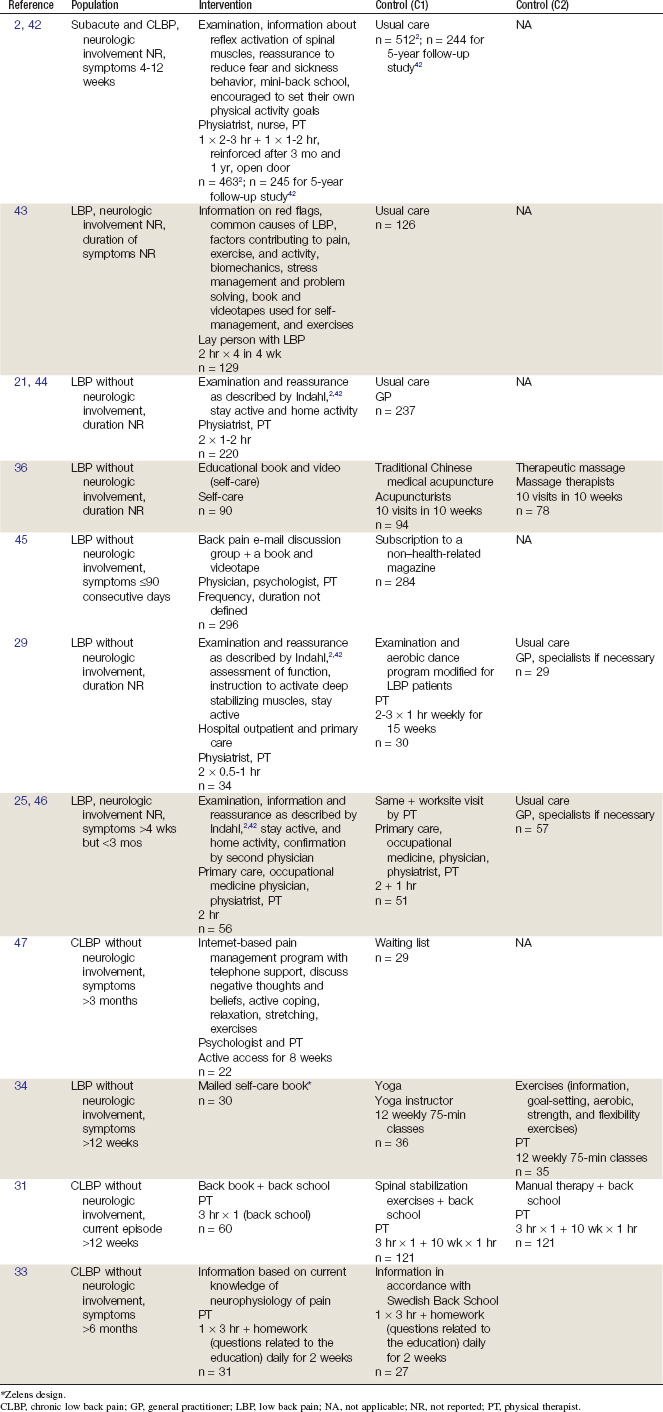

Eleven RCTs and 14 reports related to those studies were identified.2,21,25,29,31,33,34,36,42–47 Their methods are summarized in Table 6-3. Their results are briefly described here.

An RCT conducted by Indahl and colleagues2,42 included LBP patients at a spine clinic in Norway. Participants were patients with subacute or chronic (4 to 12 weeks) LBP who were referred to the clinic; excluded were pregnant women on sick leave for LBP and patients with LBP lasting longer than 12 weeks. The intervention group (initially, n = 463; 5-year follow-up, n = 245) were assigned to treatment consisting of an examination, information about reflex activation of spinal muscles, reassurance to reduce fear and sickness behavior, mini-back school, and encouragement to set their own physical activity goals. The control group (initially, n = 512; 5-year follow-up, 244) consisted of usual care. Pain and disability outcomes were not measured in this study. This study was considered of higher quality.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree