VOMITING

Marideth C. Rus, MD and Cara B. Doughty, MD, Med

Vomiting is the forceful oral expulsion of gastric contents associated with contracture of the abdominal and chest wall musculature. Vomiting may be caused by a number of problems in diverse organ systems. Vomiting is extremely common in the pediatric emergency department (ED), and usually represents a transient response to a self-limited infectious, chemical, or psychological insult. However, vomiting may also be the primary presentation of significant gastrointestinal, infectious, neurologic, or metabolic disorders requiring immediate evaluation and treatment to prevent morbidity and mortality. Thus, an orderly approach to diagnosis is crucial.

Vomiting is a complex act with multiple phases: pre-ejection, retching, and ejection phases. Gastric relaxation and retroperistalsis occur in the first phase, followed by rhythmic contractions of chest and abdominal wall muscles against a closed glottis in the retching phase. In the ejection phase, contraction of the abdominal muscles combines with relaxation of the esophageal sphincter to result in ejection. “Projectile” vomiting should be concerning as a sign of gastric outlet obstruction such as pyloric stenosis.

Recent therapeutic advances arise from an evolving understanding of neurotransmitter activity in the central nervous system (CNS), GI tract, and other sites. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) receptors are prevalent in the CNS and gut and participate in the induction of emesis. Use of serotonin receptor antagonists (such as ondansetron) has proven to be successful in decreasing or preventing emesis associated with many chemotherapeutic and radiotherapeutic cancer treatments, in emetogenic poisonings, and in children with viral gastroenteritis. Increasing evidence shows that ondansetron use in pediatric patients with viral gastroenteritis is safe, effective in reducing emesis, and unlikely to mask underlying pathology in appropriately selected patients.

A related complaint, often heard in the ED, is that of young infants who “spit up.” This refers to the nonforceful reflux of milk into the mouth, which often accompanies eructation. Such nonforceful regurgitation of gastric or esophageal contents is most often physiologic and of little consequence, although it occasionally represents a significant disturbance in esophageal function with clinical consequences for the infant.

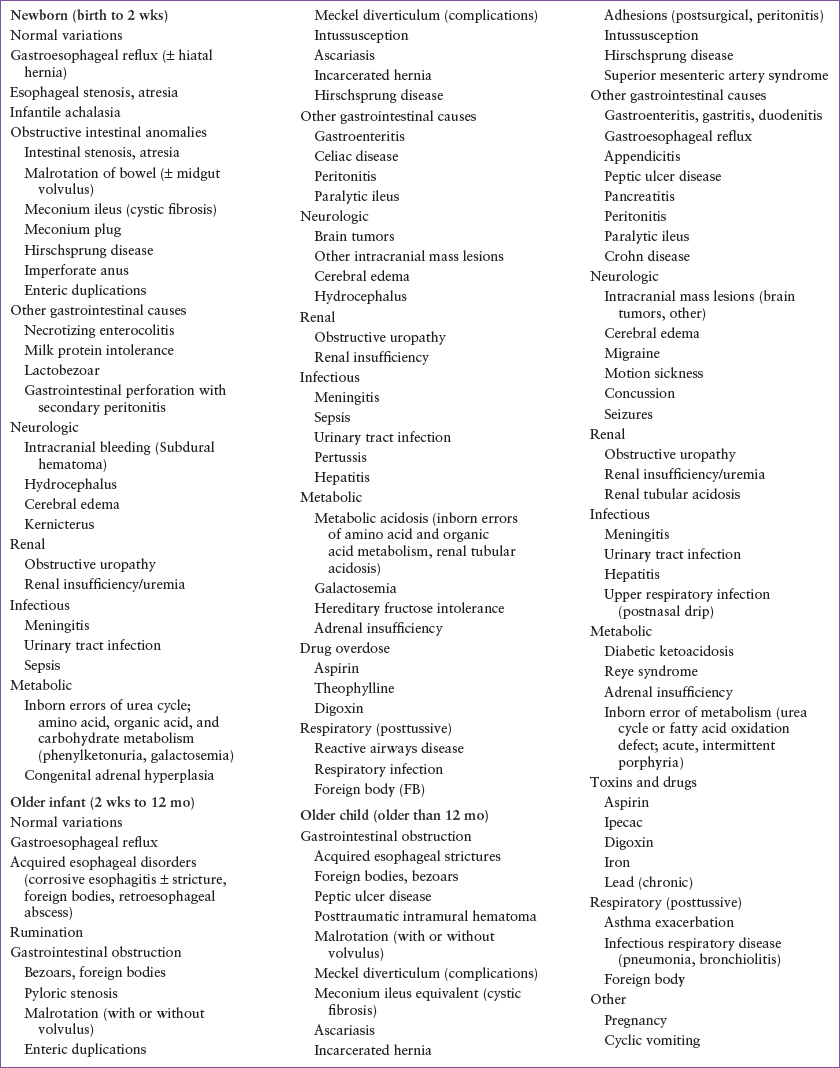

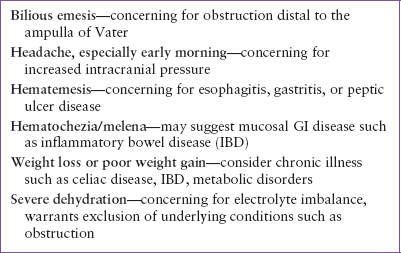

It is convenient to attempt to organize the many diverse causes of regurgitation and vomiting into age-related categories (Table 77.1). Although there is considerable overlap, the most common and serious entities can be easily organized into such groupings.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

General Approach

Given the myriad causes of vomiting an orderly approach to the differential diagnosis of this symptom is critical. Three clinical features should guide initial evaluation and management: The child’s age, evidence of obstruction, and signs or symptoms of extra-abdominal disease. Other important considerations include appearance of the vomitus, overall degree of illness (including the presence and severity of dehydration or electrolyte imbalance), and associated GI symptoms.

History

The history should focus on the key elements noted above. The patient’s age is often significant because certain critical entities (especially those that cause intestinal obstruction) are seen predominantly in neonates, older infants, or children beyond the first year of life. Evidence of obstruction, including abdominal pain, obstipation, nausea, distention, and increasing abdominal girth, is sought in addition to vomiting. Associated GI symptoms may include diarrhea and anorexia. The suspicion of significant extra-abdominal organ system disease is raised by neurologic symptoms such as severe headache, stiff neck, blurred vision or diplopia, clumsiness, personality or school performance change, or persistent lethargy or irritability; by genitourinary symptoms such as flank pain, dysuria, urgency and frequency, hematuria, or amenorrhea; by infectious complaints such as fever, sore throat, or rash; or by respiratory complaints such as cough, increased work of breathing, or chest pain (Tables 77.2 and 77.3). Other associated GI symptoms may include diarrhea, anorexia, flatulence, and frequent eructation with reflux.

The appearance of the vomitus (by history and inspection when a specimen is available) is often helpful in establishing the site of pathology. Undigested food or milk should suggest reflux from the esophagus or stomach caused by lesions such as esophageal atresia (in the neonate), gastroesophageal reflux (GER), or pyloric stenosis. Bilious vomitus suggests obstruction distal to the ampulla of Vater, although it may occasionally be seen with forceful prolonged vomiting of any cause when the pylorus is relaxed. Fecal material in the vomitus is seen with obstruction of the lower gastrointestinal tract. “Coffee-grounds” emesis suggests blood that has been exposed to gastric acid. Hematemesis usually reflects a bleeding site in the upper GI tract; its evaluation is detailed in Chapter 28 Gastrointestinal Bleeding.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should begin by evaluating the overall degree of toxicity. Are there signs of sepsis or poor perfusion? Is there the inconsolable irritability of meningitis? Are there signs of severe dehydration or concern for symptomatic hypoglycemia? Does the child exhibit the bent-over posture, apprehensive look, and pained avoidance of unnecessary movement typical of peritoneal irritation in appendicitis? Next, attention is directed to the abdominal examination. Are there signs of obstruction such as ill-defined tenderness, distention, high-pitched bowel sounds (or absent sounds in ileus), or visible peristalsis? A complete physical examination must include a search for signs of neurologic, infectious, toxic/metabolic, and genitourinary causes, as well as an evaluation of hydration status (see Chapter 17 Dehydration).

TABLE 77.1

VOMITING AND REGURGITATION: PRINCIPAL CAUSES BY USUAL AGE OF ONSET AND ETIOLOGY

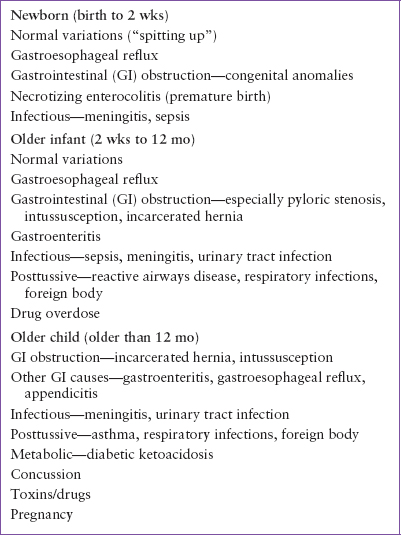

TABLE 77.2

LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES OF VOMITING

The diverse nature of causes for vomiting makes a routine laboratory or radiologic screen impossible. The history and physical examination must guide the approach in individual patients. Certain well-defined clinical pictures demand urgent radiologic workup. For example, abdominal pain and bilious vomiting in an infant requires supine and upright plain films, as well as a limited upper GI series for evaluation of congenital obstructive anomalies such as malrotation. A child with paroxysms of colicky abdominal pain and grossly bloody stools requires immediate ultrasound for rapid diagnosis of intussusception, or in clear-cut cases should proceed directly to an air-contrast enema for both diagnosis and reduction of the intussusception. Other situations require no imaging studies (e.g., a typical case of viral gastroenteritis). In many cases, cultures or serum chemical analyses are essential for making a diagnosis (e.g., meningitis, aspirin toxicity, urinary tract infection [UTI], pregnancy) or for guiding management (e.g., degree of metabolic derangement in severe dehydration, pyloric stenosis, diabetic ketoacidosis). For most straightforward, common illnesses (e.g., gastroenteritis, respiratory infections with posttussive emesis), laboratory investigation is unwarranted.

TABLE 77.3

COMMON CAUSES OF VOMITING

APPROACH TO CHILDREN BY AGE GROUPS

With these introductory concepts in mind, we can approach the differential diagnosis of the principal causes of vomiting on an age-related basis. An algorithm for such an approach that uses the key clinical features previously outlined is illustrated in Figure 77.1.

TABLE 77.4

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH SIGNIFICANT UNDERLYING CAUSES OF VOMITING

Neonates

A careful history should focus on the perinatal history, onset and duration of vomiting, nature of the vomitus, associated GI symptoms, and the presence of symptoms referable to other organ systems. Onset of vomiting in the first days of life should always prompt evaluation for one of the common congenital GI anomalies that cause obstruction, such as esophageal or intestinal atresia or web, malrotation, meconium ileus, or Hirschsprung disease. If the vomiting is bilious, bright yellow, or green, an urgent surgical consultation is required. In most cases, a serious and possibly life-threatening mechanical obstruction may be the cause of bilious vomiting. All neonates in whom the possibility of GI obstruction is entertained must have immediate flat and upright abdominal films and an upper GI series. Other clinical features, such as toxicity, dehydration, and lethargy, attest to the length of time of the obstruction and its severity. Except for some cases of malrotation, most neonates with a congenital basis for their bowel obstruction will present during their initial nursery stay; only rarely will the first presentation be in the ED. In those rare cases where an intestinal atresia presents to the ED in the first few days of life, infants will have vomiting since birth, evidence of obstruction with abdominal distention and bilious emesis, and plain abdominal films may show findings such as the “double bubble” of duodenal atresia. Correction of dehydration and metabolic abnormalities, nasogastric decompression, and surgical consultation are the most immediate ED interventions. Neonates or infants with malrotation and volvulus may present with abdominal pain (crying, drawing up their knees, poor feeding), with evidence of obstruction (bilious emesis), or an acute abdomen (abdominal distention or rigidity). Malrotation is confirmed by the abnormal radiographic location of the duodenal–jejunal junction (upper GI series) and/or the cecum (contrast enema). Immediate fluid resuscitation, GI decompression, and surgical consultation are indicated.

Infants with Hirschsprung disease most commonly present with delayed passage of meconium in the nursery, but may also present later with a distended abdomen and bilious vomiting. Children with delayed diagnosis may also present with Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis, with foul-smelling diarrhea, fever, and abdominal distention, or progress to life-threatening toxic megacolon. Prompt recognition and treatment of electrolyte imbalance, antibiotics, and surgical consultation are essential.

Other serious causes of neonatal vomiting that may present to the ED include infection, such as meningitis, sepsis, pyelonephritis, omphalitis, or necrotizing enterocolitis (it should be noted that such serious infections may not be accompanied by fever in the neonate); increased intracranial pressure (ICP) related to cerebral edema, subdural hematoma, or hydrocephalus; metabolic acidosis or hyperammonemia caused by the inborn errors of amino acid and organic acid metabolism; and renal insufficiency or obstruction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree