Introduction

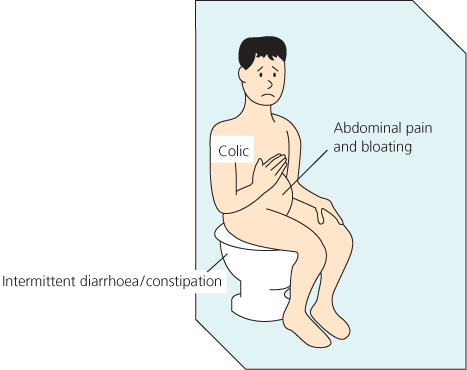

The assessment and management of visceral pain are essential skills for all clinicians regardless of specialty. Visceral pain is something that everyone has experienced to some degree, but for some this can become a major disruption to everyday life. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), a dysfunctional bowel syndrome, has been estimated to account for 40–50% of all gastroenterological consultations worldwide (Figure 7.1). Dysmenorrhoea is estimated to affect 50% of menstruating women, with 10% being forced to abstain from work for a few days each month and 30% reporting no benefit from medical treatment. Myocardial ischaemia from atherosclerosis, the most frequent cause of cardiac pain, is the most common cause of death in the United States. Although common, disentangling symptoms and signs of acute visceral pathology and chronic dysfunctional pain can be a challenge for the most skilled clinician.

Pathophysiology of Visceral Pain

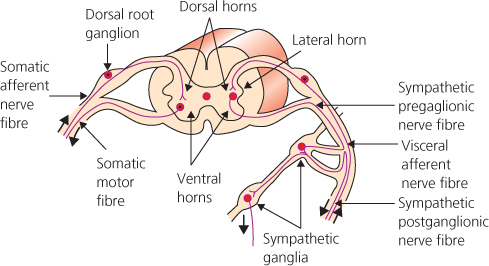

Viscera have 1% of the primary afferent innervation of somatic structures and have a much smaller cortical representation. They converge on second order neurones in the spinal cord with input from other viscera and somatic structures, which then diverge within the central nervous system (CNS). This explains the diffuse and poorly defined nature of visceral pain and also the pattern of referred pain (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 Some of the differences and similarities between visceral and somatic pain

| Visceral | Somatic | |

| Character | Dull, Colicky, Diffuse | Sharp |

| Receptor Stimuli | Distension | Cutting, Chemical |

| Ischaemia | Burns, Direct Trauma | |

| Inflammation | ||

| Primary Hyperalgesia | Yes | Yes |

| Secondary Hyperalgesia | Yes, at referral site | Yes, around site of damage |

| Summation | Yes | No |

| Localisation | Diffuse, often referred | Precise, not referred |

Adapted from McMahon, SB, Dmitrieva, N & Koltzenburg, M (1995) British Journal of Anaesthesia, 75, 132–144

The sensitivity of visceral structures varies enormously. Early surgeons, using only local anaesthesia for laparotomy, found large and small bowel insensitive to cutting, burning, crushing and tearing when applied to healthy viscera. However, viscera are sensitive to other forms of stimuli, such as distension, ischaemia and inflammation, when low intensity receptors become more responsive and previously ‘silent’ high threshold receptors are also recruited.

Visceral Pain Pathways

After nociceptor activation impulses are transmitted along slow unmyelinated C fibre tracts. There are two main types of fibre, a peptide secreting (such as substance P) and a non-peptide secreting type. It is the former type that is the most abundant and important for producing visceral hyperalgesia. These pain fibres travel alongside autonomic nerves to synapse in the dorsal horn (Figure 7.2).

The traditional view is that visceral pain transmission is carried in a few major pathways, although other pathways such as the dorsal columns, the spino (trigemino)-parabrachioamygdaloid pathway and the spinohypothalmic pathway may also be involved. As outlined in Chapter 2, peripheral and central sensitisation can develop, with a resultant increase in pain.

Visceral Pain Assessment

History and Examination

A detailed pain history is the corner stone of every assessment (Chapter 3). For visceral pain, there are some features in particular that should be elicited during the history. The main characteristics of visceral pain are outlined in Box 7.1 and should be asked about during assessment.

- Intensity of pain is not linked to tissue damage

- Diffuse and poorly localised

- Can be colicky in nature

- Referred to body wall

- Classically felt in the midline (due to embryonic innervation)

- Visceral hyperalgesia

- Associated with autonomic symptoms and signs such as sweating, flushing and anxiety, palpitations, hypertension/hypotension

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree