Viral Hepatitis

Marsha Kay

Although a number of recent developments have increased our understanding of the causes and consequences of viral hepatitis, the various agents responsible for viral hepatitis have been present for several thousand years. Epidemic jaundice associated with fever, anorexia, malaise, and fatigue was described by Hippocrates more than 2000 years ago. From the 1940s through the 1960s hepatitis A and hepatitis B were differentiated as separate clinical entities. In 1970 Dane et al. identified the viral particle responsible for hepatitis B infection. Feinstone identified the hepatitis A virus (HAV) in 1972, and in 1989 an immunoassay was developed to detect antibodies to hepatitis C virus (HCV). In 1994 the hepatitis C viral particle was identified by immunoelectron microscopic study in Japan. In 1993 research tests became available to detect the antibody to hepatitis E, although the virus was first described in 1983. Although investigators became aware of hepatitis E in the 1980-1990s, the agent was retrospectively identified as having caused a large epidemic of viral hepatitis in India in 1955 and a second major outbreak there in 1980, with a high fatality rate among pregnant women. Research is ongoing to identify “new hepatitis viruses” to join the list of currently recognized viruses, which include the agents responsible for hepatitis A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and GB infection.

According to recent data from the U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the annual incidence of new cases of hepatitis A and B viral infection in the United States is decreasing. The most dramatic decreases have been in the pediatric population as a result of pediatric vaccination strategies for both hepatitis A and B. After a decline in the incidence of acute hepatitis C infection in the 1990s, since 2003 the rates have plateaued, with a slight increase in the reported cases in 2006, the most recent year for which data are available. The prevalence of each type of hepatitis in the United States varies by patient age. In adults, hepatitis B is the most common, accounting for approximately 50% of cases, followed by hepatitis A (30%) and hepatitis C (20%); hepatitis D and hepatitis E account for less than 1% of the cases. The relative prevalence and recognition of hepatitis C are anticipated to increase in the coming years and because of the high likelihood of developing chronic infection, this entity will likely be the most prevalent form of hepatitis in adults in the United States. In children, hepatitis A is the most common form in the United States (50%) and hepatitis B the second most common (30%), with hepatitis C accounting for approximately 20% of the cases. With the significant decrease in the rates of hepatitis A and B infection in pediatric patients, the relative prevalence of hepatitis C infection will likely increase, and it is anticipated that hepatitis C will become the most prevalent form of hepatitis in children and adolescents in the United States. The relative increase in the importance of HCV infection is the consequence of two factors: effective vaccination strategies for hepatitis A and hepatitis B, which have decreased the rates of hepatitis A and hepatitis B infection in children, young adults and their contacts, and the high rate of chronic infection following hepatitis C infection. Hepatitis D and hepatitis E account for less than 1% of the cases of pediatric viral hepatitis in the United States, and as in adults, hepatitis E occurs almost exclusively in patients who have traveled to areas in which the infection is endemic.

HEPATITIS A

Hepatitis A is a RNA virus in the family Picornaviridae. Infection with HAV results in acute illness only. Most infected patients are asymptomatic. Hepatitis A occurs most frequently in developing countries, in which the prevalence may reach 100% and most individuals have been infected by the age of 5 years. Approximately 30% of adults in the United States have had hepatitis A infection. It is estimated that only one fifth of individuals with hepatitis A undergo diagnostic testing, the results of which by law must be reported to the CDC. For example, 29,000 cases were reported in the United States in 1990, but 130,000 to 150,000 cases of hepatitis A were estimated to have occurred that year. CDC data in 2006 the most recent year available indicate a significant decrease in reported HAV cases in the United States (3579 cases reported, estimated 15,000 acute clinical cases, and 32,000 new infections)

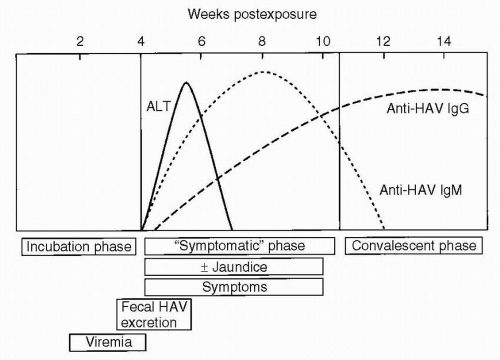

with similar rates now in all age groups (0.7-1.4 cases/100,000 population). This is the result of availability of HAV vaccine starting in 1995, with the largest comparative decreases in the rates of infection during childhood. The mean incubation period for hepatitis A virus is 28 days, with a range of 15 to 50 days. Patients are contagious up to 14 days before the development of symptoms and for 1 week after jaundice appears (Fig. 6.1). The primary route of transmission is fecal-oral, but transmission from contaminated shellfish and rare percutaneous and transfusion-associated transmission also occurs. The diagnosis is established by the presence of elevated levels of anti-HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM), which can be detected at 5 weeks following exposure, at the time when clinical symptoms have appeared. This antibody typically persists for 3 to 4 months. Anti-HAV IgG, which can usually be detected 4 months after exposure, may persist for years. Children with hepatitis A, especially those younger than 3 years, are usually asymptomatic. If they do have symptoms, they are similar to those of a viral upper respiratory tract infection. The frequency of clinical symptoms is higher in adolescents and adults, and their symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, dark-colored urine, and anorexia, may be more severe. The fraction of individuals hospitalized with acute HAV infection increases with increasing age with a 22% rate in children less than age 5 and a rate of 52% in persons ≥60 years of age. Fulminant hepatic failure from hepatitis A is uncommon, but can be fatal, with approximately 100 cases per year in the United States (0.3% death rate). A long-term carrier state does not exist.

with similar rates now in all age groups (0.7-1.4 cases/100,000 population). This is the result of availability of HAV vaccine starting in 1995, with the largest comparative decreases in the rates of infection during childhood. The mean incubation period for hepatitis A virus is 28 days, with a range of 15 to 50 days. Patients are contagious up to 14 days before the development of symptoms and for 1 week after jaundice appears (Fig. 6.1). The primary route of transmission is fecal-oral, but transmission from contaminated shellfish and rare percutaneous and transfusion-associated transmission also occurs. The diagnosis is established by the presence of elevated levels of anti-HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM), which can be detected at 5 weeks following exposure, at the time when clinical symptoms have appeared. This antibody typically persists for 3 to 4 months. Anti-HAV IgG, which can usually be detected 4 months after exposure, may persist for years. Children with hepatitis A, especially those younger than 3 years, are usually asymptomatic. If they do have symptoms, they are similar to those of a viral upper respiratory tract infection. The frequency of clinical symptoms is higher in adolescents and adults, and their symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, dark-colored urine, and anorexia, may be more severe. The fraction of individuals hospitalized with acute HAV infection increases with increasing age with a 22% rate in children less than age 5 and a rate of 52% in persons ≥60 years of age. Fulminant hepatic failure from hepatitis A is uncommon, but can be fatal, with approximately 100 cases per year in the United States (0.3% death rate). A long-term carrier state does not exist.

Two methods are available to prevent hepatitis A infection:

Passive immunoprophylaxis

Active immunization

Before 1995, hepatitis A Ig was the only form of prophylaxis available and was administered before travel to areas of endemicity or following acute exposure. Areas in which hepatitis A is endemic include Mexico, the Caribbean, South America, Central America, Africa, and Asia (not including Japan). This type of passively acquired immunity lasts 12 weeks or less, and Ig must be readministered in cases of ongoing exposure. Hepatitis A Ig is also indicated for:

Acute exposure, if given within 14 days after exposure to household members or intimate contacts of individuals with acute hepatitis A

Outbreaks in day care or custodial settings

Common source outbreaks

Two hepatitis A vaccines are now available. Immunization is now routinely recommended for all children 12 months of age or older regardless of state of residence. Coadministration of HAV vaccine with other immunizations is not associated with impairment of vaccine induced immunity. In addition to all children, vaccination is recommended for travelers and high-risk populations, which include American Indians, Alaskans, illicit drug users, laboratory workers, handlers of primate animals, and individuals with chronic liver disease, patients with clotting factor disorders, and men who have sex with men. A booster dose is required for both hepatitis A vaccines. Vaccination is being evaluated for postexposure prophylaxis, especially in areas of a confined outbreak. In this setting both vaccine or hepatitis A immunoglobulin are highly efficacious and are associated with a reduction of the rate of acute hepatitis A infection to ≤5% of exposed contacts.

HEPATITIS B

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus in the family Hepadnaviridae with a mean incubation period of 120 days (range, 45-160 days). Currently there are 8 genotypes (A-H) and two subtypes (Aa/Ae, Ba/Bj). It is extremely common worldwide, with more than 300 million carriers. Areas in which hepatitis B is highly endemic include China, sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, the Mediterranean basin, and Alaska (among the Eskimo population). In Asia, the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carrier rate is 5% to 20% of the general population. The annual rate of HBV infection in the United States is estimated to be about 50,000 cases, which has decreased by more than 60% from the 1990s and represents approximately 20% of the mean number of new infections in the 1980s. Overall in the United States, approximately 0.5% to 0.7% of the population are long-term carriers (approximately 1.25 million individuals), with 4.9% of the population having been infected with Hepatitis B at some point in their lifetime. The mortality rate is 1.4%. The major risk factor for HBV infection in children is having a mother who is positive for HBsAg, especially if the mother is also

positive for hepatitis B early antigen (HBeAg). Without immunoprophylaxis, rates of transmission from mother to infant may approach 90%, and up to 30% to 90% of these children remain long-term carriers until at least 30 years of age. Children adopted from areas of endemicity are another population at risk in the United States. Currently the majority of new childhood infections in the United States excluding perinatal infections are found in immigrant children themselves, children born to infected immigrant women, and children who acquire HBV horizontally within these households or enclaves. Children also can acquire HBV infection intravenously from drugs and blood products, following tattooing and piercing, in the course of institutionalized care (especially when the incidence of biting is high), and through high-risk sexual behaviors.

positive for hepatitis B early antigen (HBeAg). Without immunoprophylaxis, rates of transmission from mother to infant may approach 90%, and up to 30% to 90% of these children remain long-term carriers until at least 30 years of age. Children adopted from areas of endemicity are another population at risk in the United States. Currently the majority of new childhood infections in the United States excluding perinatal infections are found in immigrant children themselves, children born to infected immigrant women, and children who acquire HBV horizontally within these households or enclaves. Children also can acquire HBV infection intravenously from drugs and blood products, following tattooing and piercing, in the course of institutionalized care (especially when the incidence of biting is high), and through high-risk sexual behaviors.

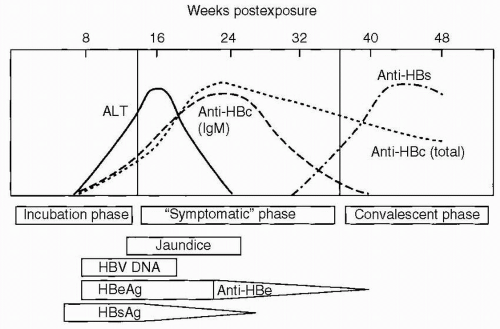

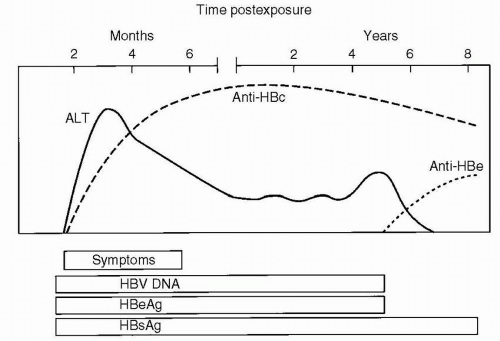

Hepatitis B Serology

HBsAg is acquired by almost all infected individuals. Detection is coincident with symptom onset and increased values of serum liver chemistries. It is typically detectable 45 days following infection, and levels may decrease before symptoms resolve (Fig. 6.2). Persistence of this antigen for 6 months or longer indicates a long-term carrier state (Fig. 6.3). HBeAg, a low-molecular-weight soluble protein associated with the viral core, is a marker of infectivity. Anti-HBc is antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). HBcAg is not detectable by commercial testing. Initially, anti-HBc is an IgM antibody and subsequently an IgG antibody. Levels increase shortly after symptom onset and the appearance of HBsAg, and anti-HBc typically persists for many years. Its presence indicates acute, resolved, or chronic infection, but anti-HBc is not detected following immunization. The development of anti-HBe indicates a reduced risk for transmission of HBV, but not immunity. The development of antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs) indicates immunity, and anti-HBs is acquired after effective immunization or the resolution of infection. HBV DNA is found in the viral core and is currently the best measure for viral replication. Rarely, patients may be positive for both HBsAg and anti-HBs. This finding likely represents the development of immunity to vaccine virus in a patient who was already a long-term carrier of wild-type virus and is associated with chronic disease.

Clinical symptoms are more frequent with HBV infection than with HAV infection, and fulminant hepatitis develops in a higher proportion of patients. Symptoms of infection include anorexia, malaise, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Chronic disease develops in approximately 10% of adults, 50% of older children who are infected and in 90% of infants who acquire the infection vertically. The high rate of perinatal acquisition reflects the large viral inoculum in maternal blood during birth and in maternal secretions after birth, and the infant’s immune tolerance to the virus. Factors associated with immune tolerance to HBV infection and therefore with chronic infection include downregulation of the expression of immune recognition signals on the surface of infected hepatocytes, viral antigenic variation, suppressing the immune response by inducing tolerance, exhausting viral specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes, and interfering with cytokine function. In children with chronic HBV infection, who had acquired the infection vertically, transaminase levels are characteristically normal or minimally elevated, usually up to 100 international unit (IU)/L, with simultaneously high levels of viral replication. In older children who acquire the infection horizontally, the pattern of transaminase elevation may be more similar to that of adults. Chronic HBV infection can result in chronic hepatitis, liver necrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The risk for HCC in an individual with chronic HBV infection can be 200 to 500 times greater than that of an unaffected patient, and the risk correlates with the duration of

infection. In Taiwan, 80% of children with HCC are anti-HBe seropositive and patients with chronic HBsAg carriage have a 25% lifetime risk of developing HCC, with highest rates in patients who are HBeAg positive. Hepatitis C infection also significantly increases the risk for HCC in pediatric patients. The rate of HCC has decreased by 75% in children between the ages of 6 and 14 years in Taiwan after universal HBV vaccination was initiated there in 1984.

infection. In Taiwan, 80% of children with HCC are anti-HBe seropositive and patients with chronic HBsAg carriage have a 25% lifetime risk of developing HCC, with highest rates in patients who are HBeAg positive. Hepatitis C infection also significantly increases the risk for HCC in pediatric patients. The rate of HCC has decreased by 75% in children between the ages of 6 and 14 years in Taiwan after universal HBV vaccination was initiated there in 1984.

Effective strategies are available to prevent HBV infection, including vaccination and passive immunoprophylaxis. The two types of HBV vaccine are plasma-derived vaccine and recombinant vaccine; recombinant vaccine is used primarily because plasma-derived vaccine is no longer manufactured in the United States. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIg) is used in conjunction with the vaccine. When HBIg and HBV vaccines are administered at birth and an appropriate vaccination schedule is followed, perinatal HBV infection is prevented in more than 90% of infants, whereas the efficacy rate is 75% to 80% when either HBV vaccine or HBIg is given alone. HBV vaccination and the administration of HBIg are indicated for:

Neonates with an HBsAg-positive mother

Intimate contacts of a patient with acute HBV infection

HBsAg-negative individuals who sustain an HBsAg-positive needlestick injury

Universal hepatitis B vaccination is recommended for all infants at birth by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All children and adolescents who have not been immunized against HBV should begin the series as soon as possible. In addition to the groups listed in the preceding text, HBV vaccination is recommended for intimate or household contacts of a patient with chronic HBV infection, ethnic populations at high risk of HBV infection, all injection drug users, sexually active individuals with more than one partner per 6-month period or a history of a sexually transmitted disease, sexually active homosexual men, health care personnel, residents and staff of institutions for developmentally disabled individuals, patients undergoing hemodialysis, patients with bleeding disorders who require clotting factor concentrates, travelers to areas in which HBV infection is endemic, and inmates of juvenile detention or correctional facilities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree