CHAPTER 12

Vertigo

(Dizziness, Lightheadedness)

Presentation

The patient who has dizziness may have a nonspecific complaint that must be further differentiated into either an altered somatic sensation (giddiness, wooziness, disequilibrium), orthostatic lightheadedness (sensation of fainting), or the sensation of the environment (or patient) spinning (true vertigo). Vertigo is a symptom produced by asymmetric input from the vestibular system because of damage or dysfunction of the labyrinth, vestibular nerve, or central vestibular structures of the brain stem. Vertigo is a symptom, not a diagnosis. It is customarily categorized into central and peripheral causes. Peripheral causes account for 80% of cases of vertigo, with benign positional vertigo, vestibular neuritis, and Meniere disease being most common. Peripheral causes tend to be more severe and sudden in onset but more benign in course when compared to central causes. Vertigo is frequently accompanied by nystagmus, resulting from ocular compensation for the unreal sensation of spinning. Nausea and vomiting also are common accompanying symptoms of true vertigo.

What To Do:

Clarify the type of dizziness. Have the patient express how he feels in his own words (without using the word dizzy). Determine whether the patient is describing true vertigo (a feeling of movement of one’s body or surroundings), has a sensation of an impending faint, or has a vague, unsteady feeling. Ask about any factors that precipitate the dizziness and any associated symptoms, as well as how long the dizziness lasts. Ask about drugs or toxins that could be responsible for the dizziness.

Clarify the type of dizziness. Have the patient express how he feels in his own words (without using the word dizzy). Determine whether the patient is describing true vertigo (a feeling of movement of one’s body or surroundings), has a sensation of an impending faint, or has a vague, unsteady feeling. Ask about any factors that precipitate the dizziness and any associated symptoms, as well as how long the dizziness lasts. Ask about drugs or toxins that could be responsible for the dizziness.

If the symptoms were accompanied by neurologic symptoms, such as diplopia, visual deficits, sudden collapse, or unilateral weakness or numbness, consider a transient ischemic attack (TIA) as a possible cause and consider MRI and neurologic consultation.

If the symptoms were accompanied by neurologic symptoms, such as diplopia, visual deficits, sudden collapse, or unilateral weakness or numbness, consider a transient ischemic attack (TIA) as a possible cause and consider MRI and neurologic consultation.

If the problem is near-syncope or orthostatic lightheadedness, consider potentially serious causes, such as heart disease, cardiac dysrhythmias, and blood loss or possible medication effects (see Chapter 11).

If the problem is near-syncope or orthostatic lightheadedness, consider potentially serious causes, such as heart disease, cardiac dysrhythmias, and blood loss or possible medication effects (see Chapter 11).

With a sensation of disequilibrium or an elderly patient’s feeling that he is unsteady and going to fall, look for diabetic peripheral neuropathy (lower-extremity sensory loss) and muscle weakness. These patients should be referred to their primary care physicians for management of underlying medical problems and possible adjustment of their medications.

With a sensation of disequilibrium or an elderly patient’s feeling that he is unsteady and going to fall, look for diabetic peripheral neuropathy (lower-extremity sensory loss) and muscle weakness. These patients should be referred to their primary care physicians for management of underlying medical problems and possible adjustment of their medications.

If there is lightheadedness that is unrelated to changes in position and posture and there is no evidence of disease found on physical examination and laboratory evaluation, refer these patients to their primary care physicians for evaluation for possible depression or other psychological conditions.

If there is lightheadedness that is unrelated to changes in position and posture and there is no evidence of disease found on physical examination and laboratory evaluation, refer these patients to their primary care physicians for evaluation for possible depression or other psychological conditions.

If the patient is having true vertigo, try to determine if this is the more benign form of peripheral vertigo or the potentially more serious form of central vertigo.

If the patient is having true vertigo, try to determine if this is the more benign form of peripheral vertigo or the potentially more serious form of central vertigo.

Peripheral vertigo (vestibular neuritis [the most common form of peripheral vertigo], labyrinthitis, and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo [BPPV]) is generally accompanied by an acute vestibular syndrome with rapid onset of severe symptoms associated with nausea and vomiting, spontaneous unidirectional horizontal nystagmus, and postural instability. Romberg testing, when positive, will show a tendency to fall or lean in one direction only, toward the involved side.

Peripheral vertigo (vestibular neuritis [the most common form of peripheral vertigo], labyrinthitis, and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo [BPPV]) is generally accompanied by an acute vestibular syndrome with rapid onset of severe symptoms associated with nausea and vomiting, spontaneous unidirectional horizontal nystagmus, and postural instability. Romberg testing, when positive, will show a tendency to fall or lean in one direction only, toward the involved side.

Central vertigo (inferior cerebellar infarction, brain stem infarction, multiple sclerosis, and tumors) is generally less severe—with vertical, pure rotatory, or multidirectional nystagmus—and is more likely to be found in elderly patients with risk factors for stroke. It is possibly accompanied by focal neurologic signs or symptoms, including cerebellar abnormalities (asymmetric finger-to-nose and rapid alternating movement examinations) and the inability to walk caused by profound ataxia.

Central vertigo (inferior cerebellar infarction, brain stem infarction, multiple sclerosis, and tumors) is generally less severe—with vertical, pure rotatory, or multidirectional nystagmus—and is more likely to be found in elderly patients with risk factors for stroke. It is possibly accompanied by focal neurologic signs or symptoms, including cerebellar abnormalities (asymmetric finger-to-nose and rapid alternating movement examinations) and the inability to walk caused by profound ataxia.

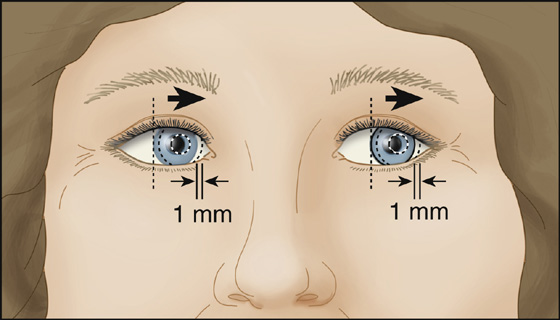

When examining the patient for nystagmus, have the patient follow your finger with his eyes as it moves a few degrees to the left and then to the right (not to extremes of gaze) (Figure 12-1), and note whether there are more than the normal two to three beats of nystagmus before the eyes are still. Determine the direction of the nystagmus (horizontal, vertical, or rotatory) and whether or not fixating the patient’s gaze reduces the nystagmus (a peripheral finding).

When examining the patient for nystagmus, have the patient follow your finger with his eyes as it moves a few degrees to the left and then to the right (not to extremes of gaze) (Figure 12-1), and note whether there are more than the normal two to three beats of nystagmus before the eyes are still. Determine the direction of the nystagmus (horizontal, vertical, or rotatory) and whether or not fixating the patient’s gaze reduces the nystagmus (a peripheral finding).

Figure 12-1 The eye should only move a few degrees to the left or right when examining for nystagmus.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is the most common cause of vertigo in the elderly. Nystagmus may be detected when the eyes are closed by watching the bulge of the cornea moving under the lid.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is the most common cause of vertigo in the elderly. Nystagmus may be detected when the eyes are closed by watching the bulge of the cornea moving under the lid.

Examine ears for cerumen, foreign bodies, otitis media, and hearing loss. Ideally, check for speech discrimination. (Can the patient differentiate between the words kite, flight, right?) Abnormalities may be a sign of an acoustic neuroma.

Examine ears for cerumen, foreign bodies, otitis media, and hearing loss. Ideally, check for speech discrimination. (Can the patient differentiate between the words kite, flight, right?) Abnormalities may be a sign of an acoustic neuroma.

Examine the cranial nerves and perform a complete neurologic examination that includes testing of cerebellar function (using rapid alternating movement, finger-to-nose, and gait tests when possible). Check the corneal blink reflexes and, if absent on one side in a patient who does not wear contact lenses, again consider acoustic neuroma. Complete the rest of a full general physical examination.

Examine the cranial nerves and perform a complete neurologic examination that includes testing of cerebellar function (using rapid alternating movement, finger-to-nose, and gait tests when possible). Check the corneal blink reflexes and, if absent on one side in a patient who does not wear contact lenses, again consider acoustic neuroma. Complete the rest of a full general physical examination.

Decide, on the basis of the aforementioned examinations, whether the cause is central (brain stem, cerebellar, multiple sclerosis) or peripheral (vestibular organs, eighth nerve). Suspicion of central lesions requires further workup, MRI (the most appropriate imaging study in these cases) when available, otolaryngologic or neurologic consultation, or hospital admission.

Decide, on the basis of the aforementioned examinations, whether the cause is central (brain stem, cerebellar, multiple sclerosis) or peripheral (vestibular organs, eighth nerve). Suspicion of central lesions requires further workup, MRI (the most appropriate imaging study in these cases) when available, otolaryngologic or neurologic consultation, or hospital admission.

Peripheral lesions, on the other hand, although more symptomatic, are more likely to be treatable and managed on an outpatient basis. Always consider how well the patient is tolerating symptoms after therapy and what the social conditions are at home before sending the patient home.

Peripheral lesions, on the other hand, although more symptomatic, are more likely to be treatable and managed on an outpatient basis. Always consider how well the patient is tolerating symptoms after therapy and what the social conditions are at home before sending the patient home.

When peripheral vestibular neuronitis or labyrinthitis is suspected, because of sudden onset of persistent, severe vertigo with nausea, vomiting, and horizontal nystagmus with gait instability but preserved ability to ambulate, treat symptoms of vertigo with IV dimenhydrinate 50 mg (Dramamine) or meclizine (Antivert) 25 mg PO. Benzodiazepines, such as Valium or lorazepam (Ativan), may be used to potentiate the effects of the antihistamine. These symptom controlling medications should only be used for the first 48 to 72 hours. Remember that there are no confirmatory tests for vestibular neuritis and many of the symptoms overlap with those of posterior infarction; so, have a low index of suspicion to obtain an MRI to rule out central causes in elderly patients (older than 60 years old), anyone with other neurologic signs or symptoms, or patients with accompanying headache or an atypical course.

When peripheral vestibular neuronitis or labyrinthitis is suspected, because of sudden onset of persistent, severe vertigo with nausea, vomiting, and horizontal nystagmus with gait instability but preserved ability to ambulate, treat symptoms of vertigo with IV dimenhydrinate 50 mg (Dramamine) or meclizine (Antivert) 25 mg PO. Benzodiazepines, such as Valium or lorazepam (Ativan), may be used to potentiate the effects of the antihistamine. These symptom controlling medications should only be used for the first 48 to 72 hours. Remember that there are no confirmatory tests for vestibular neuritis and many of the symptoms overlap with those of posterior infarction; so, have a low index of suspicion to obtain an MRI to rule out central causes in elderly patients (older than 60 years old), anyone with other neurologic signs or symptoms, or patients with accompanying headache or an atypical course.

Nausea may be treated with ondansetron (Zofran) or prochlorperazine (Compazine). If there are no contraindications (e.g., glaucoma), a patch of transdermal scopolamine (Transderm Sc

Nausea may be treated with ondansetron (Zofran) or prochlorperazine (Compazine). If there are no contraindications (e.g., glaucoma), a patch of transdermal scopolamine (Transderm Sc p) can be worn for 3 days. Some authors recommend hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax), and others suggest that corticosteroids (methylprednisolone [Solu-Medrol], prednisone) significantly improve recovery in patients with vestibular neuronitis. Nifedipine (Procardia) had been used to alleviate motion sickness but is no better than scopolamine patches and should not be used for patients who have postural hypotension or who take beta-blockers.

p) can be worn for 3 days. Some authors recommend hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax), and others suggest that corticosteroids (methylprednisolone [Solu-Medrol], prednisone) significantly improve recovery in patients with vestibular neuronitis. Nifedipine (Procardia) had been used to alleviate motion sickness but is no better than scopolamine patches and should not be used for patients who have postural hypotension or who take beta-blockers.

If the patient does not respond, he may require hospitalization for further parenteral treatment and evaluation.

If the patient does not respond, he may require hospitalization for further parenteral treatment and evaluation.

After discharge, treat persistent symptoms of peripheral vertigo with lorazepam, 1 to 2 mg qid; meclizine (Antivert), 12.5 to 25 mg qid; or dimenhydrinate, 25 to 50 mg qid. Prochlorperazine suppository, 25 mg bid, or ondansetron (Zofran) PO or ODT can be used for persistent nausea, and bed rest should be recommended as needed until symptoms improve.

After discharge, treat persistent symptoms of peripheral vertigo with lorazepam, 1 to 2 mg qid; meclizine (Antivert), 12.5 to 25 mg qid; or dimenhydrinate, 25 to 50 mg qid. Prochlorperazine suppository, 25 mg bid, or ondansetron (Zofran) PO or ODT can be used for persistent nausea, and bed rest should be recommended as needed until symptoms improve.

Arrange for follow-up in all patients treated in the outpatient setting.

Arrange for follow-up in all patients treated in the outpatient setting.

BPPV is associated with brief (less than 1 minute) episodes of severe vertigo that are precipitated by movements, such as rolling over in bed, extending the neck to look upward, or bending over and flexing the neck to look down. Often patients can recall a short period between the time they assumed a particular position and the onset of the spinning sensation. The diagnosis can be confirmed by performing the Dix-Hallpike maneuver.

BPPV is associated with brief (less than 1 minute) episodes of severe vertigo that are precipitated by movements, such as rolling over in bed, extending the neck to look upward, or bending over and flexing the neck to look down. Often patients can recall a short period between the time they assumed a particular position and the onset of the spinning sensation. The diagnosis can be confirmed by performing the Dix-Hallpike maneuver.

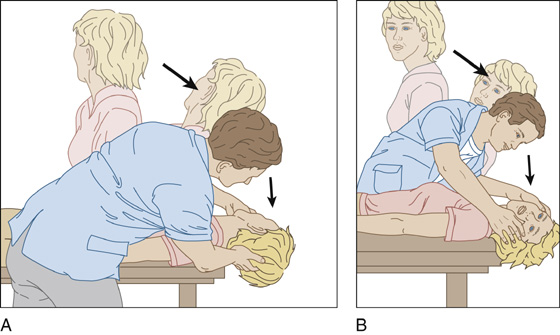

When symptoms are consistent with BPPV, when there are no auditory or neurologic symptoms, and when the patient is no longer symptomatic, perform a Dix-Hallpike (formerly Nylen-Barany) maneuver (Figure 12-2, A and B) to confirm the diagnosis and determine which ear is involved.

When symptoms are consistent with BPPV, when there are no auditory or neurologic symptoms, and when the patient is no longer symptomatic, perform a Dix-Hallpike (formerly Nylen-Barany) maneuver (Figure 12-2, A and B) to confirm the diagnosis and determine which ear is involved.

Figure 12-2 A, The patient’s head is 30 degrees below horizontal. With her head turned to the right, quickly lower the patient to the supine position. B, Repeat with her head turned to the left.

To perform the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, have the patient sit up for at least 30 seconds, then lie back, and quickly hang his head over the end of the stretcher, with his head turned 45 degrees to the right. Wait 30 seconds for the appearance of nystagmus or the sensation of vertigo. Repeat the maneuver on the other side. When this maneuver produces positional nystagmus after a brief latent period lasting less than 30 seconds, it indicates benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. The ear that is down when the greatest symptoms of nystagmus are produced is the affected ear, which can be treated using canalith-repositioning maneuvers. An equivocal test is not a contraindication to performing canalith-repositioning maneuvers.

To perform the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, have the patient sit up for at least 30 seconds, then lie back, and quickly hang his head over the end of the stretcher, with his head turned 45 degrees to the right. Wait 30 seconds for the appearance of nystagmus or the sensation of vertigo. Repeat the maneuver on the other side. When this maneuver produces positional nystagmus after a brief latent period lasting less than 30 seconds, it indicates benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. The ear that is down when the greatest symptoms of nystagmus are produced is the affected ear, which can be treated using canalith-repositioning maneuvers. An equivocal test is not a contraindication to performing canalith-repositioning maneuvers.

To prevent nausea and vomiting when these symptoms are not tolerable for the patient, premedicate him with an antiemetic such as metoclopramide (Reglan), 10 mg IV, or ondansetron (Zofran), 4 mg IV. These maneuvers can be performed quickly at the bedside, thereby moving semicircular canal debris to a less sensitive part of the inner ear (utricle). This can produce rapid results, often providing much satisfaction to both patient and clinician.

To prevent nausea and vomiting when these symptoms are not tolerable for the patient, premedicate him with an antiemetic such as metoclopramide (Reglan), 10 mg IV, or ondansetron (Zofran), 4 mg IV. These maneuvers can be performed quickly at the bedside, thereby moving semicircular canal debris to a less sensitive part of the inner ear (utricle). This can produce rapid results, often providing much satisfaction to both patient and clinician.

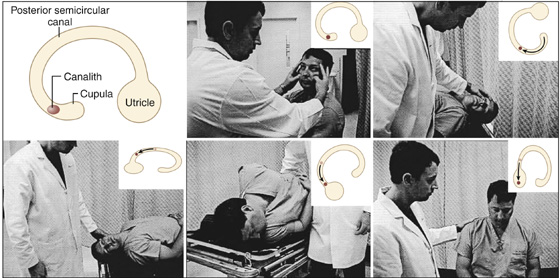

The most well studied of these maneuvers is the Epley maneuver. With the patient seated, the patient’s head is rotated 45 degrees toward the affected ear. The patient is then tilted backward to a head-hanging position, with the head kept in the 45-degree rotation. The patient is held in this position (same as the Dix-Hallpike position with the affected ear down) until the nystagmus and vertigo abate (at least 20 seconds, but most clinicians recommend 4 minutes in each position). The head is then turned 90 degrees toward the unaffected ear and kept in this position for another 3 to 4 minutes. With the head remaining turned, the patient is then rolled onto the side of the unaffected ear. This may again provoke nystagmus and vertigo, but the patient should again remain in this position for 3 to 4 minutes. Finally, the patient is moved to the seated position, and the head is tilted down 30 degrees, allowing the canalith to fall into the utricle. This position is also held for an additional 3 to 4 minutes (Figure 12-3).

The most well studied of these maneuvers is the Epley maneuver. With the patient seated, the patient’s head is rotated 45 degrees toward the affected ear. The patient is then tilted backward to a head-hanging position, with the head kept in the 45-degree rotation. The patient is held in this position (same as the Dix-Hallpike position with the affected ear down) until the nystagmus and vertigo abate (at least 20 seconds, but most clinicians recommend 4 minutes in each position). The head is then turned 90 degrees toward the unaffected ear and kept in this position for another 3 to 4 minutes. With the head remaining turned, the patient is then rolled onto the side of the unaffected ear. This may again provoke nystagmus and vertigo, but the patient should again remain in this position for 3 to 4 minutes. Finally, the patient is moved to the seated position, and the head is tilted down 30 degrees, allowing the canalith to fall into the utricle. This position is also held for an additional 3 to 4 minutes (Figure 12-3).

Figure 12-3 Epley maneuver. Top (left to right), The first window is a legend for the inset, which is a simplified representation of a posterior semicircular canal. This figure shows the Epley canalith-repositioning maneuver for the left semicircular canal. The patient’s head is turned 45 degrees toward the affected ear, with the patient holding the physician’s arm for support. The patient is then lowered to a supine position. The patient’s head remains turned 45 degrees and should hang off the end of the bed. Bottom, In the third position, the patient’s head is rotated to face the opposite shoulder. Next, the patient is rolled onto his side, taking care to keep the head rotated. The patient is now returned to a seated position with the head tilted forward. (Adapted from Koelliker P, Summers R, Hawkins B: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Ann Emerg Med 37:392-398, 2001, with permission from The American College of Emergency Physicians.)

Contraindications to these maneuvers include severe cervical spine disease, unstable cardiac disease, and high-grade carotid stenosis.

Contraindications to these maneuvers include severe cervical spine disease, unstable cardiac disease, and high-grade carotid stenosis.

Most authors recommend that the patient remain upright or semi-upright for 1 to 2 days and avoid bending over after a successful canalith repositioning. To help the patient keep from tilting his head or bending his neck, you can fit him with a soft cervical collar for the rest of the day. (The patient can sleep on a recliner with his head no lower than 45 degrees.) The patient may continue to feel off-balance for a few days and should not drive home from the medical facility.

Most authors recommend that the patient remain upright or semi-upright for 1 to 2 days and avoid bending over after a successful canalith repositioning. To help the patient keep from tilting his head or bending his neck, you can fit him with a soft cervical collar for the rest of the day. (The patient can sleep on a recliner with his head no lower than 45 degrees.) The patient may continue to feel off-balance for a few days and should not drive home from the medical facility.

The maneuvers can be repeated several times if the symptoms do not resolve on the first attempt. If the initial findings are somewhat unclear, no harm is done if the canalith-repositioning maneuver is performed on the apparently unaffected ear.

The maneuvers can be repeated several times if the symptoms do not resolve on the first attempt. If the initial findings are somewhat unclear, no harm is done if the canalith-repositioning maneuver is performed on the apparently unaffected ear.

If a patient has a complete resolution of symptoms with repositioning, other causes for the vertigo become less likely. If symptoms persist or are atypical, referral to an otorhinolaryngologist or neurologist is appropriate.

If a patient has a complete resolution of symptoms with repositioning, other causes for the vertigo become less likely. If symptoms persist or are atypical, referral to an otorhinolaryngologist or neurologist is appropriate.

What Not To Do:

Do not expect to determine the exact cause of dizziness for all patients who present for the first time. Make every reasonable attempt to determine whether or not the origin is benign or potentially serious, and then make the most appropriate disposition.

Do not expect to determine the exact cause of dizziness for all patients who present for the first time. Make every reasonable attempt to determine whether or not the origin is benign or potentially serious, and then make the most appropriate disposition.

Do not attempt provocative maneuvers if the patient is symptomatic with nystagmus at rest. Prolonged symptoms are inconsistent with BPPV, which is the only indication for doing such provocative maneuvers.

Do not attempt provocative maneuvers if the patient is symptomatic with nystagmus at rest. Prolonged symptoms are inconsistent with BPPV, which is the only indication for doing such provocative maneuvers.

Do not go through the Epley maneuvers too rapidly. Success depends on holding the patient in each position for 3 to 4 minutes.

Do not go through the Epley maneuvers too rapidly. Success depends on holding the patient in each position for 3 to 4 minutes.

Do not give antivertigo drugs to elderly patients with disequilibrium or orthostatic symptoms. These medications have sedative properties that can worsen the condition. These drugs will also not help depression if this is the underlying cause of lightheadedness.

Do not give antivertigo drugs to elderly patients with disequilibrium or orthostatic symptoms. These medications have sedative properties that can worsen the condition. These drugs will also not help depression if this is the underlying cause of lightheadedness.

Do not give long-term vestibular suppressant drugs to patients with BPPV unless you are unable to perform repositioning maneuvers and the patient’s symptoms are severe.

Do not give long-term vestibular suppressant drugs to patients with BPPV unless you are unable to perform repositioning maneuvers and the patient’s symptoms are severe.

Do not make the diagnosis of Meniere disease (endolymphatic hydrops) without the triad of paroxysmal vertigo, sensorineural deafness, and low-pitched tinnitus, along with a feeling of pressure or fullness in the affected ear that lasts for hours to days. With repeat attacks, a sustained low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss and constant tinnitus develop.

Do not make the diagnosis of Meniere disease (endolymphatic hydrops) without the triad of paroxysmal vertigo, sensorineural deafness, and low-pitched tinnitus, along with a feeling of pressure or fullness in the affected ear that lasts for hours to days. With repeat attacks, a sustained low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss and constant tinnitus develop.

Do not proceed with expensive laboratory testing or unwarranted imaging studies, especially with signs and symptoms of benign peripheral vertigo. Remember, CT will not rule out posterior fossa disease. Most causes of dizziness can be determined through obtaining a complete patient history and clinical examination. If radiographic studies are needed, MRI is the most sensitive for posterior fossa and brain stem abnormalities.

Do not proceed with expensive laboratory testing or unwarranted imaging studies, especially with signs and symptoms of benign peripheral vertigo. Remember, CT will not rule out posterior fossa disease. Most causes of dizziness can be determined through obtaining a complete patient history and clinical examination. If radiographic studies are needed, MRI is the most sensitive for posterior fossa and brain stem abnormalities.

Do not prescribe meclizine, scopolamine, and other vestibular suppressants for more than a few days during acute vestibular hypofunction caused by vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis. These drugs may actually prolong symptoms if given on a long-term basis, because they interfere with the patient’s natural compensation mechanisms within the denervated vestibular nucleus.

Do not prescribe meclizine, scopolamine, and other vestibular suppressants for more than a few days during acute vestibular hypofunction caused by vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis. These drugs may actually prolong symptoms if given on a long-term basis, because they interfere with the patient’s natural compensation mechanisms within the denervated vestibular nucleus.

Discussion

Vertigo is an illusion of motion, usually rotational, of the patient or the patient’s surroundings. The clinician responsible for evaluating this problem should consider a differential diagnosis, with special attention to whether the vertigo is central or peripheral in origin. A large number of entities cause vertigo, ranging from benign and self-limited causes, such as vestibular neuritis and BPPV, to immediately life-threatening causes, such as cerebellar infarction or hemorrhage. In general, the more violent the sensation of vertigo and the more spinning, the more likely that the lesion is peripheral. Central lesions tend to cause less intense vertigo and more vague symptoms. Peripheral causes of vertigo or nystagmus include irritation of the ear (utricle, saccule, semicircular canals) or the vestibular division of the eighth cranial (acoustic) nerve caused by toxins, otitis, viral infection, or cerumen or a foreign body lodged against the tympanic membrane. The term labyrinthitis should be reserved for vertigo with hearing changes, and the term vestibular neuronitis should be reserved for the common, transient vertigo, without hearing changes, that is sometimes associated with upper respiratory tract viral infections. Paroxysmal positional vertigo may be related to inappropriate particles (free-floating debris or otoliths) in the endolymph of the semicircular canals. If it occurs after significant trauma, suspect a basal skull fracture with leakage of endolymph or perilymph, and consider otolaryngologic referral for further evaluation.

The vestibular nerve is unique among the cranial nerves in that the neurons in this nerve, on each side, are firing spontaneously at 100 spikes/sec with the head still. With sudden loss of input from one side, there is a strong bias into the brain stem from the intact side. This large bias in neural activity causes nystagmus. The direction of the nystagmus is labeled according to the quick phase, but the vestibular deficit is actually driving the slow phase of nystagmus.

Vestibular neuritis is preceded by a common cold 50% of the time. The prevalence of vestibular neuritis peaks at 40 to 50 years of age. Vestibular neuritis is probably similar to Bell’s palsy and is thought to represent a reactivated dormant herpes infection in the Scarpa ganglion within the vestibular nerve. Viral labyrinthitis can be diagnosed if there is associated hearing loss or tinnitus at the time of presentation, but the possibility of an acoustic neuroma should be kept in mind, especially if the vertigo is mild.

Central causes include multiple sclerosis, temporal lobe epilepsy, basilar migraine, and hemorrhage or infarction or tumor in the posterior fossa. Patients with a slow-growing acoustic neuroma in the cerebellopontine angle usually do not present with acute vertigo but rather with a progressive, unilateral hearing loss, with or without tinnitus. The earliest sign is usually a gradual loss of auditory discrimination.

Vertebrobasilar arterial insufficiency can cause vertigo, usually with associated nausea, vomiting, and cranial nerve or cerebellar signs. It is commonly diagnosed in dizzy patients who are older than 50 years of age, but more often than not the diagnosis is incorrect. The brain stem is a tightly packed structure in which the vestibular nuclei are crowded in with the oculomotor nuclei, the medial longitudinal fasciculus, and the cerebellar, sensory, and motor pathways. It would be unusual for ischemia to produce only vertigo without accompanying diplopia, ataxia, or sensory or motor disturbance. Although vertigo may be the major symptom of an ischemic attack, careful questioning of the patient commonly uncovers symptoms implicating involvement of other brain stem structures. Objective neurologic signs should be present in frank infarction of the brain stem.

Nystagmus occurring in central nervous system (CNS) disease may be vertical and disconjugate, whereas inner-ear nystagmus never is. Central nystagmus is gaze directed (beats in the direction of gaze), whereas inner-ear nystagmus is direction fixed (beats in one direction, regardless of the direction of gaze). Central nystagmus is evident during visual fixation, whereas inner-ear nystagmus is suppressed.

A peripheral vestibular lesion produces unidirectional postural instability with preserved walking, whereas an inferior cerebellar stroke often causes severe postural instability and falling when walking is attempted.

If vertebrobasilar arterial insufficiency is suspected in an elderly patient who has no focal neurologic findings, it is reasonable to place such a patient on aspirin and provide him with prompt neurologic follow-up.

Either central or peripheral nystagmus can be caused by toxins, most commonly alcohol, tobacco, aminoglycosides, minocycline, disopyramide, phencyclidine, phenytoin, benzodiazepines, quinine, quinidine, aspirin, salicylates, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and carbon monoxide.

Vertigo in an otherwise healthy young child is usually indicative of benign paroxysmal vertigo that may be a migraine equivalent, especially when associated with headache.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree