CHAPTER 11

Vasovagal or Neurocardiogenic or Neurally Mediated Syncope

(Faint, Swoon)

Presentation

The patient experiences a brief loss of consciousness, preceded by a sense of warmth and nausea and awareness of passing out, with weakness and diaphoresis. The patient may or may not experience ringing in the ears or a sensation of tunnel vision. First, there is a period of sympathetic tone, with increased pulse and blood pressure, in anticipation of some stressful incident, such as bad news, an upsetting sight, or a painful procedure. Immediately after or during the stressful occurrence, there is a precipitous drop in sympathetic tone and/or surge in parasympathetic tone, resulting in peripheral vasodilatation or bradycardia, or both, leading to hypotension and causing the victim to lose postural tone, fall down, and lose consciousness.

Once the patient is in a horizontal position, normal skin color, normal pulse, and consciousness return within seconds. This time period may be extended if the patient is maintained in an upright sitting position.

Transient bradycardia and a few myoclonic limb jerks or tonic spasms (syncopal convulsions) may accompany vasovagal syncope, but there are no sustained seizures, incontinence, lateral tongue biting, palpitations, dysrhythmias, or injuries beyond a minor contusion or laceration resulting from the fall. Ordinarily, the victim spontaneously revives within 30 seconds, suffers no sequelae, and can recall the events leading up to the faint.

The whole process may transpire in an ED or a clinic setting, or a patient may have fainted elsewhere, in which case the diagnostic challenge is to reconstruct what happened to rule out other causes of syncope.

What To Do:

To prevent potential fainting spells, arrange for anyone anticipating an unpleasant experience to sit or lie down prior to the offensive event.

To prevent potential fainting spells, arrange for anyone anticipating an unpleasant experience to sit or lie down prior to the offensive event.

If an individual faints, catch her so she will not be injured in the fall, lay her supine on the floor or stretcher for 5 to 10 minutes, protect her airway, record several sets of vital signs, and be prepared to proceed with resuscitation if the episode becomes more than a simple vasovagal syncopal episode.

If an individual faints, catch her so she will not be injured in the fall, lay her supine on the floor or stretcher for 5 to 10 minutes, protect her airway, record several sets of vital signs, and be prepared to proceed with resuscitation if the episode becomes more than a simple vasovagal syncopal episode.

If a patient is brought in after fainting elsewhere, obtain a detailed history. Ask about the setting, precipitating factors, descriptions given by several eyewitnesses, and sequence of recovery. Look for evidence of painful stimuli (i.e., phlebotomy), emotional stress, or other unpleasant experiences, such as the sight of blood.

If a patient is brought in after fainting elsewhere, obtain a detailed history. Ask about the setting, precipitating factors, descriptions given by several eyewitnesses, and sequence of recovery. Look for evidence of painful stimuli (i.e., phlebotomy), emotional stress, or other unpleasant experiences, such as the sight of blood.

Consider other benign precipitating causes, such as prolonged standing (especially in the heat), recent diarrhea and dehydration, or Valsalva maneuver during urination, defecation, or cough.

Consider other benign precipitating causes, such as prolonged standing (especially in the heat), recent diarrhea and dehydration, or Valsalva maneuver during urination, defecation, or cough.

Determine if there were prodromal symptoms consistent with benign neurocardiogenic syncope, such as lightheadedness, nausea, and diaphoresis.

Determine if there were prodromal symptoms consistent with benign neurocardiogenic syncope, such as lightheadedness, nausea, and diaphoresis.

In patients in whom there is no clearly benign precipitating cause, inquire whether the collapse came without warning or whether there was seizure activity with a postictal period of confusion, or ask if there was diplopia, dysarthria, focal neurologic symptoms, or headache. Also find out if there was any chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations or if the syncope occurred with sudden standing. Is there any reason for dehydration, evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, or recent addition of a new drug?

In patients in whom there is no clearly benign precipitating cause, inquire whether the collapse came without warning or whether there was seizure activity with a postictal period of confusion, or ask if there was diplopia, dysarthria, focal neurologic symptoms, or headache. Also find out if there was any chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations or if the syncope occurred with sudden standing. Is there any reason for dehydration, evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, or recent addition of a new drug?

Obtain a medical history to determine if there have been previous similar episodes or there is an underlying cardiac problem (i.e., congestive heart failure [CHF], arrhythmias, valvular heart disease) or risk factors for coronary disease or aortic dissection. Look for previous strokes or transient ischemic attacks as well as gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Also note if there is a history of psychiatric illness.

Obtain a medical history to determine if there have been previous similar episodes or there is an underlying cardiac problem (i.e., congestive heart failure [CHF], arrhythmias, valvular heart disease) or risk factors for coronary disease or aortic dissection. Look for previous strokes or transient ischemic attacks as well as gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Also note if there is a history of psychiatric illness.

Ask about a family history of benign fainting or sudden death. (There is a familial tendency toward syncope.)

Ask about a family history of benign fainting or sudden death. (There is a familial tendency toward syncope.)

Check to see which medications the patient is taking and if any of these drugs can cause hypotension, arrhythmias, or QT prolongation.

Check to see which medications the patient is taking and if any of these drugs can cause hypotension, arrhythmias, or QT prolongation.

The performance of the physical examination should start with vital signs, to include an assessment of orthostatic hypotension. (To make the diagnosis of orthostatic hypotension as the cause of syncope, it is helpful if the patient has a true reproduction of symptoms on standing.)

The performance of the physical examination should start with vital signs, to include an assessment of orthostatic hypotension. (To make the diagnosis of orthostatic hypotension as the cause of syncope, it is helpful if the patient has a true reproduction of symptoms on standing.)

Other important features of the physical examination include neurologic findings, such as diplopia, dysarthria, papillary asymmetry, nystagmus, ataxia, gait instability, and slowly resolving confusion or lateral tongue biting, as well as cardiac findings, such as carotid bruits, jugular venous distention, rales, and a systolic murmur (of aortic stenosis or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy).

Other important features of the physical examination include neurologic findings, such as diplopia, dysarthria, papillary asymmetry, nystagmus, ataxia, gait instability, and slowly resolving confusion or lateral tongue biting, as well as cardiac findings, such as carotid bruits, jugular venous distention, rales, and a systolic murmur (of aortic stenosis or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy).

Do an ECG. The value of this study is not its ability to identify the cause of syncope but, by identifying any abnormality, its ability to provide clues to an underlying cardiac cause. Because an ECG is relatively inexpensive and essentially risk free, it should be done on virtually all patients with syncope, with the possible exception of young, healthy patients with an obvious situational or vasovagal cause.

Do an ECG. The value of this study is not its ability to identify the cause of syncope but, by identifying any abnormality, its ability to provide clues to an underlying cardiac cause. Because an ECG is relatively inexpensive and essentially risk free, it should be done on virtually all patients with syncope, with the possible exception of young, healthy patients with an obvious situational or vasovagal cause.

For patients in whom a clear cause of syncope cannot be determined after history and physical examination, initiate cardiac monitoring.

For patients in whom a clear cause of syncope cannot be determined after history and physical examination, initiate cardiac monitoring.

Routine blood tests rarely yield diagnostically useful information. In most cases, blood tests serve only to confirm a clinical suspicion. If acute blood loss is a possibility, obtain hemoglobin and hematocrit measures (although examination of stool for blood may be more accurate).

Routine blood tests rarely yield diagnostically useful information. In most cases, blood tests serve only to confirm a clinical suspicion. If acute blood loss is a possibility, obtain hemoglobin and hematocrit measures (although examination of stool for blood may be more accurate).

A head CT scan should only be obtained in patients with focal neurologic symptoms and signs or new-onset seizure activity or to rule out hemorrhage in patients with head trauma or headache.

A head CT scan should only be obtained in patients with focal neurologic symptoms and signs or new-onset seizure activity or to rule out hemorrhage in patients with head trauma or headache.

Admit patients with any of the following to the hospital:

Admit patients with any of the following to the hospital:

A history of congestive heart failure or ventricular arrhythmias

A history of congestive heart failure or ventricular arrhythmias

Associated chest pain or other symptoms compatible with acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection, or pulmonary embolus

Associated chest pain or other symptoms compatible with acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection, or pulmonary embolus

Evidence of significant congestive heart failure or valvular heart disease on physical examination

Evidence of significant congestive heart failure or valvular heart disease on physical examination

ECG findings of ischemia, arrhythmia (either bradycardia or tachycardia), prolonged QT interval, or bundle branch block (BBB)

ECG findings of ischemia, arrhythmia (either bradycardia or tachycardia), prolonged QT interval, or bundle branch block (BBB)

Concomitant conditions that require inpatient treatment

Concomitant conditions that require inpatient treatment

Consider admission for patients with syncope and any of the following:

Consider admission for patients with syncope and any of the following:

Age older than 60 years

Age older than 60 years

History of coronary artery disease or congenital heart disease

History of coronary artery disease or congenital heart disease

Family history of unexpected sudden death

Family history of unexpected sudden death

Exertional syncope in younger patients without an obvious benign cause for the syncope

Exertional syncope in younger patients without an obvious benign cause for the syncope

A complaint of shortness of breath

A complaint of shortness of breath

A hematocrit of less than 30%

A hematocrit of less than 30%

An initial systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg or severe orthostatic hypotension

An initial systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg or severe orthostatic hypotension

Patients not requiring admission should be referred to an appropriate follow-up physician and should be instructed to avoid precipitating factors, such as extreme heat, dehydration, postexertional standing, alcohol, and certain medications. It is also reasonable to recommend an increase in salt and fluid intake to decrease syncopal episodes in the younger patient.

Patients not requiring admission should be referred to an appropriate follow-up physician and should be instructed to avoid precipitating factors, such as extreme heat, dehydration, postexertional standing, alcohol, and certain medications. It is also reasonable to recommend an increase in salt and fluid intake to decrease syncopal episodes in the younger patient.

Referral for tilt-table testing is appropriate when there has been recurrent, unexplained syncope without evidence of organic heart disease or after a negative cardiac workup.

Referral for tilt-table testing is appropriate when there has been recurrent, unexplained syncope without evidence of organic heart disease or after a negative cardiac workup.

After full recovery, explain to the patient with classic vasovagal syncope that fainting is a common physiologic reaction and that, in future recurrences, she can recognize the early lightheadedness and prevent a full swoon by lying down or sitting and putting her head between her knees.

After full recovery, explain to the patient with classic vasovagal syncope that fainting is a common physiologic reaction and that, in future recurrences, she can recognize the early lightheadedness and prevent a full swoon by lying down or sitting and putting her head between her knees.

Consider restricting unprotected driving, swimming, and diving for those with severe and recurrent episodes of vasovagal syncope without a trigger.

Consider restricting unprotected driving, swimming, and diving for those with severe and recurrent episodes of vasovagal syncope without a trigger.

What Not To Do:

Do not allow family members to stand while being given bad news, do not allow parents to stand while watching their children being sutured, and do not allow patients to stand while being given shots or undergoing venipuncture.

Do not allow family members to stand while being given bad news, do not allow parents to stand while watching their children being sutured, and do not allow patients to stand while being given shots or undergoing venipuncture.

Do not traumatize the fainting victim by using ammonia capsules, slapping, or dousing with cold water.

Do not traumatize the fainting victim by using ammonia capsules, slapping, or dousing with cold water.

Do not obtain a head CT scan unless there are focal neurologic symptoms and signs, unless there has been true seizure activity, or unless you want to rule out intracranial hemorrhage.

Do not obtain a head CT scan unless there are focal neurologic symptoms and signs, unless there has been true seizure activity, or unless you want to rule out intracranial hemorrhage.

Do not refer patients for EEG studies unless there were witnessed tonic-clonic movements or postevent confusion.

Do not refer patients for EEG studies unless there were witnessed tonic-clonic movements or postevent confusion.

Do not obtain routine blood tests unless there is a clinical indication based on the history and physical examination.

Do not obtain routine blood tests unless there is a clinical indication based on the history and physical examination.

Do not refer patients with obvious vasovagal syncope for tilt-table testing.

Do not refer patients with obvious vasovagal syncope for tilt-table testing.

Do not discharge syncope patients who have a history of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, or ventricular dysrhythmia; patients who complain of chest pain; patients who have physical signs of significant valvular heart disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, or focal neurologic disorder; or patients who have electrocardiographic findings of ischemia, bradycardia, tachycardia, increased QT interval, or BBB.

Do not discharge syncope patients who have a history of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, or ventricular dysrhythmia; patients who complain of chest pain; patients who have physical signs of significant valvular heart disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, or focal neurologic disorder; or patients who have electrocardiographic findings of ischemia, bradycardia, tachycardia, increased QT interval, or BBB.

Discussion

Syncope is defined as a transient loss of consciousness and muscle tone. It is derived from the Greek word synkoptein, “to cut short.” Presyncope is “the feeling that one is about to pass out.”

Most commonly, the cause of syncope in young adults is vasovagal or neurocardiogenic. Observation of the sequence of stress, relief, and fainting makes the diagnosis, but, better yet, the whole reaction can usually be prevented. Although most patients suffer no sequelae, vasovagal syncope with prolonged asystole can produce seizures and rare incidents of death. The differential diagnosis of loss of consciousness is extensive; therefore loss of consciousness should not immediately be assumed to be caused by vasovagal syncope.

Several triggers may induce neurally mediated syncope, including emotional stress (anxiety; an unpleasant sight, sound, or smell) or physical stress, such as pain, hunger, dehydration, illness, anemia, and fatigue. In adolescents, symptoms of syncope may be related to the menstrual cycle or be associated with starvation in patients with eating disorders. Situational triggers include cough, micturition, and defecation.

Orthostatic hypotension is the second most common cause of syncope after neurocardiogenic syncope and is most frequently seen in the elderly. There are many causes of orthostatic hypotension, the most common of which are hypovolemia (vomiting, diarrhea, hemorrhage, pregnancy) and drugs (antihypertensives, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, diuretics, and phenothiazines).

Neurologic causes of syncope include seizures, transient ischemic attacks, and migraine headaches, as well as intracranial hemorrhage.

Cardiac-related syncope is potentially the most dangerous form of syncope. Patients with known cardiac disease who also experience syncope have a significantly increased incidence of cardiac-related death. The patients at risk have ischemic heart disease, most significantly congestive heart failure, congenital heart disease, and valvular heart disease (particularly aortic valvular disorder) or are taking drugs that produce QT prolongation or are known to induce torsades de pointes (i.e., amiodarone, tricyclics, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], phenothiazines, macrolides, quinolones, and many antifungals—becoming very dangerous in combination with one another).

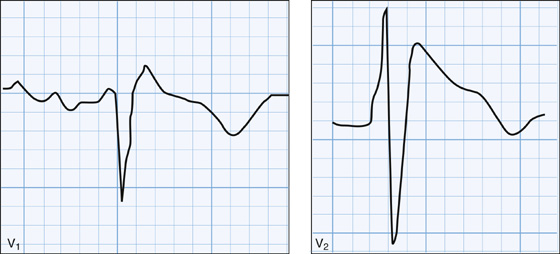

Brugada syndrome is a rare but potentially lethal familial dysrhythmic syndrome characterized by an ECG that shows a partial right BBB with elevation of ST segments in leads V1-3, which have a peculiar downsloping with inverted T waves (Figure 11-1).

Figure 11-1 Brugada syndrome (V1 and V2).

Danger signs for cardiac-related syncope include sudden onset without warning or syncope—preceded by palpitations as well as associated chest pain, shortness of breath—and illicit drug use. Other danger signs are postexertional syncope (think about fixed cardiac lesions) and syncope that occurred while the patient was seated or lying down.

Other serious causes of syncope that should be considered (and are usually accompanied by distinctive signs and symptoms) are aortic dissection and rupture, pulmonary embolism, ectopic pregnancy with rupture, and carotid artery dissection.

Elderly patients have a higher percentage of underlying cardiovascular, pulmonary, and cerebrovascular disease, and therefore, syncope in the elderly is more often associated with a serious problem than it is in younger patients. Myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, and aortic stenosis are examples of this. Carotid sinus syncope (secondary to, for example, tight collars, head turning, and shaving) is almost exclusively a disease of the elderly. If suspected, carotid sinus massage can confirm the diagnosis but should not be attempted if the patient has carotid bruits, ventricular tachycardia, or recent stroke or myocardial infarction. Arrhythmias, particularly bradyarrhythmias, are also more common in the elderly. For these reasons, elderly patients more often require hospitalization for monitoring and further diagnostic testing.

It should also be appreciated that elderly patients are more prone to abnormal responses to common benign situational stresses, including postural changes, micturition (exacerbated by prostatic hypertrophy in men), coughing (especially in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and defecation associated with constipation. These abnormal responses are compounded by the effects of underlying illnesses and medications, including anticholinergics, antihypertensives (including eye drops with beta-blocker activity), and central nervous system (CNS) depressants.

Often, no single cause of syncope in the elderly can be identified. Patients improve after several small changes, however, including discontinuance of unnecessary medications, avoidance of precipitating events, and the use of support stockings or fludrocortisone (Florinef acetate), 0.05 to 0.4 mg PO qd (usual: 0.1 mg PO qd), for postural hypotension (off label).

Tilt-table testing has become a common component of the diagnostic evaluation of syncope. The accuracy of tilt testing is unknown, and a positive tilt test only diagnoses a propensity for neurocardiogenic events. Despite these limitations, referral for tilt-table testing can be useful in patients with recurrent, unexplained syncope and a suspected neurocardiogenic cause (a patient having typical vasovagal symptoms) but without a clear precipitant; in patients without cardiac disease or in whom cardiac testing has been negative; and in patients in whom testing clearly reproduces the symptoms.

Many pharmacologic agents have been used in the treatment of recurrent neurocardiogenic syncope. The relatively favorable natural history of neurocardiogenic syncope, with a spontaneous remission rate of 91%, makes it difficult to assess the efficacy and necessity of these drugs.

Psychiatric evaluation is recommended in young patients with recurrent, unexplained syncope without cardiac disease who have frequent episodes associated with many varied prodromal symptoms as well as other complaints.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree