Chapter 3 Use of Medmarx Data for the Support and Development of Perioperative Medication Policy

Perioperative evidence-based practice depends on synthesis of data from internal and external benchmarking (Titler, 2006). Development of perioperative medication policy should be guided by synthesis of these data and by recommendations from perioperative professional organizations and regulatory agencies. However, limited evidence of this synthesis exists in the literature to guide policy development for safe medication practices for this critical specialty (Beyea et al, 2003). Responding to this gap in knowledge, the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and the Uniformed Services of the Health Sciences Graduate School of Nursing collaborated in a partnership to analyze perioperative medication error reports from the MEDMARX database. The Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN), and other volunteer experts served as the USP Council of Experts, which reviewed and provided input for the final report, MEDMARX Data Report: A Chartbook of Medication Error Findings From the Perioperative Settings From 1998-2005 (Hicks et al, 2006).

The MEDMARX database contains a unique classification system for medication errors that supports coding of all records of medication errors according to the extent of harm, including potential errors causing no harm. These invaluable data have the capability to guide the development of medication policy in the high-risk perioperative environment through identification of causative factors and trends. Yet, there is minimal descriptive summary in the literature on how MEDMARX data are currently being used to support the development of perioperative medication policy. The purpose of this chapter is to review results of an initial research study that describes how MEDMARX data are being used to support the development and revision of a population health medication policy across the perioperative continuum. This will allow individuals responsible for the development and updating of perioperative medication policies to apply and use evidence-based practice to determine and set policy. Chapter 5 provides further details related to MEDMARX data with specifics of medication error prevention.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Population health focuses on improving health outcomes, eliminating health disparities, and reducing health care costs for a particular group of people (Bibb, 2002; Department of Defense, 2005a; Department of Defense, 2005b; Bibb et al, 2006). Central to improving the outcome for surgical patient populations is the reduction of patient safety risk factors. The U.S. epidemic of patient safety problems was documented in the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) report in 1998 (Institute of Medicine, 1998). This landmark report indicated that 98,000 deaths occurred each year as a result of medical errors. More recently, the IOM report from November 2003 titled Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care calls for a unified national health information infrastructure as a requirement to make patient safety a standard of care (Institute of Medicine, 2003).

Patient Safety Risk

With medical mistakes ranking sixth among the leading causes of death in U.S. hospitals today, it is urgent to identify probable causative factors (Nosek et al, 2005). According to recent USP data, a large portion of medical mistakes in the hospital setting are medication errors, with 235,000 errors reported in the 2003 MEDMARX annual summary report (Hicks et al, 2004b) and 950,000 adverse drug events reported in MEDMARX as of January 2006 (USP, 2006).

In an immediate effort to decrease patient safety risk in hospitals across the United States, the U.S. Congress approved a billion-dollar patient safety initiative (National Patient Safety Foundation, 2005). Shortly after Congress endorsed these measures for all health care facilities, many literary and Web-based resources emerged. Some of these initiatives assessed and evaluated practices at both the unit and hospital level, with increased analyses of systems within health care facilities.

The MEDMARX Database

USP owns another older and less-used database for voluntary reporting of errors, the Medication Error Reporting (MER) database. This database contains roughly one-tenth the data sets reported to MEDMARX. Although it is a free, anonymous service, MER lacks the number of data sets needed to generate reports of trends from its users. Although the number of medication errors should not be the sole criterion for determining a useful database, it does afford the analysis of causative factor trends (Department of Defense, 2005a). Therefore the MEDMARX database is preferred over the MER database for secondary analysis. As stated in the USP e-newsroom, “This third annual report, Summary of Information Submitted to MEDMARX in the Year 2001: A Human Factors Approach to Medication Errors, is the most comprehensive compilation of medication error data submitted by hospitals and health systems nationwide” (Borden and Gifford, 2006).

Unsafe Perioperative Practices

The operating room and postanesthesia care unit share unsafe medication administration practices, including nonspecific policies for unit stock medications, communication of verbal orders, and written case card preference sheets. MEDMARX data has identified these specific unsafe practices in all phases of the perioperative continuum throughout the literature. Once the cause is known, systems involved in the unsafe process can be evaluated and gaps identified to further develop or modify existing medication policy (Beyea et al, 2003; Hicks et al, 2004a).

In 2002 The Joint Commission (TJC) announced plans to establish its first set of National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs) (TJC, 2008a). In 2005 The Joint Commission NPSGs added reconciliation of medications across the continuum of care as their eighth specific goal (TJC, 2006). The 2009 NPSG Goal 8 requires accredited institutions to “accurately and completely reconcile medications across the continuum of care” (TJC, 2008b). This goal provides elements of performance on how to achieve the NPSGs, requiring that all patients have a complete list of medications that they are currently taking on their chart at all times. This information is communicated throughout each phase of their care. In addition, a process allowing for comparison of ordered medication to medications on the patient’s current list is required (TJC, 2008b). NPSG.08.01.01 requires that medications at all times must be accurate. Elements of Performance for NPSG.08.01.01 require that upon admission the patient must have a current list of medications that includes the medication, dose, route, and frequency. The patient and members of the family may participate in creating an accurate list. Any discrepancies should be addressed to prevent the potential for a medication error. NPSG.08.02.01 requires communication of the reconciled medication list to the provider of the next level of service. When the list is reconciled, the process should be documented. NPSG.08.03.01 involves patient education at the time of discharge. The patient and/or family should receive education and a current list of reconciled medications. The patient should be instructed to discard any old medication list he or she may have and replace it with the current version. NPSG.08.04.01 states that facilities may use a modified medication reconciliation process in areas such as the emergency department, convenient care, office-based surgery, outpatient radiology, ambulatory care, and behavioral care (TJC, 2008b). The importance of medication reconciliation is essential to patient safety.

Professional organizations such as AORN and ASPAN have also assisted perioperative nurses and perioperative practitioners with identification of gaps within their practice environment and have provided valuable tools to improve patient safety in risk-prone areas. AORN has multiple resources for the perioperative nurse in practice and as guides for updating current medication policy, such as AORN Safe Medication Administration Took Kit (AORN, 2005), Safe Medication Practices in the Perioperative Setting (AORN, 2009), Managing the Patient Receiving Moderate Sedation/Analgesia (AORN, 2009), and Managing the Patient Receiving Local Anesthesia (2009). These are valuable resources for the perioperative nurse for the development of medication competencies and increasing awareness of safe medication administration by the perioperative team. In addition, ASPAN’s Position Statement on Safe Medication Administration (ASPAN, 2005) provides guiding principles and guidelines for the safe administration of medications. The nurse should be knowledgeable about these valuable resources and use them in the process of policy development or revision of existing medication administration policies.

An Underutilized Asset

MEDMARX data are being used for performance improvement projects in the surgical population, revealing the database as a user-friendly tool (Beyea et al, 2003; Hicks et al, 2007). Perioperative nurses and practitioners could benefit from a comprehensive list of studies using the MEDMARX database for a quick review of existing trends in medication errors. From this list, perioperative nurses could envision the body of evidence-based research studies available and integrate this knowledge into future medication policy and best medication practices (Hamric and Hanson, 2003). In addition, medication error trends that have not been explored, and thus require further study, will be easily identified as gaps in the current body of knowledge. It is only through the exploration of these gaps that nurses and practitioners can achieve a healthy, safe outcome for the surgical patient population.

Significant gaps relating to medication error causes have been identified over the past 6 years, yet there exists no collection of interventions that have been taken to correct these causative factors, as identified in medication policy documents in the literature (Cousins, 1998; Cowley et al, 2001; Beyea et al, 2003, Santell et al, 2003; Beyea et al, 2004; Hicks et al, 2004a, Hicks et al, 2004b, Jones et al, 2004; Niccolai et al, 2004; Nosek et al, 2005). Practitioners such as advanced practice nurses (APNs) are an excellent resource and are often consulted to update policy based on the latest standards, while incorporating evidence-based findings in the defense of modified policy (Heitkemper and Bond, 2006). A list of studies using secondary analysis of the MEDMARX database to support perioperative medication policy, and assist in the identification of future research needed, would be an invaluable asset for the perioperative nurse, the APN, or anyone involved with policy development (Zuzelo, 2003; Nicoll and Beyea, 1999).

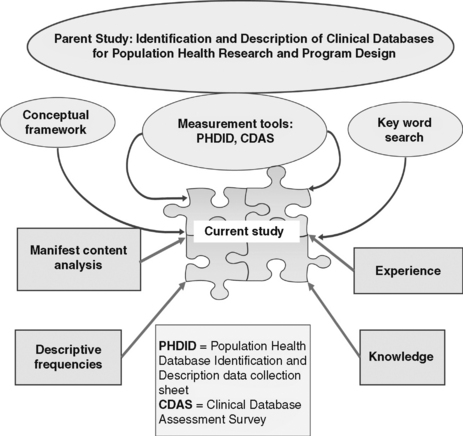

The study described in this chapter was conducted using the methodologic approach and data collection tools piloted in a study conducted by Bibb et al (2006) to identify and describe clinical databases and data sets used to support development of population health programs and population health policy (Figure 3-1). The study described focused specifically on the use of MEDMARX data in the support and development of medication policy in the perioperative setting.

Conceptual Definition—Perioperative Medication Safety Policy

The definition of perioperative medication policy includes standards set by regulatory agencies—The Joint Commission, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Health and Human Services—in conjunction with recommendations from professional organizations (AORN and ASPAN), state requirements, and facility instructions, which guide the development of evidence-based medication practices in the perioperative environment (Department of Defense, 2005a; Titler, 2006; AORN, 2009).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree