Introduction

Lean manufacturing, referred to commonly as “lean,” comes from the Japanese manufacturing process management philosophy derived mostly from the Toyota Motor Company. Lean was popularized in the 1990s with the publication of the best seller The Machine That Changed the World, a book authored by Massachusetts Institute of Technology research scientists studying global manufacturing practices. This book by Womack, Jones, and Roos describes the manufacturing techniques behind Toyota’s success and shows how, when implemented, these systems resulted in defect reduction, improved cost efficiency, higher productivity, and greater customer satisfaction. The results were remarkable: cars with one-third the defects, built in half the factory space, using half the man-hours. The Machine That Changed the World explained what lean production is, how it really works, and how it inevitably spread beyond the auto industry. It was not until 2001 that health care organizations began applying lean principles to processes outside of manufacturing.

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine Report, To Err is Human, challenged organizations to find better tools to effectively address cost and quality challenges. Those looking outside of health care for fresh approaches were impressed with the results seen in manufacturing companies using lean. The challenge would be to translate manufacturing tools into health care processes.

Lean Manufactoring Translated into Health Care

Like manufacturing, health care delivery systems are often large, complex organizations with widespread waste and inefficiencies. For this reason the Toyota production system methods are attractive to health care leaders. Lean methods place the customer first, are obsessed with highest quality, safety, and staff satisfaction while succeeding economically. Beyond broad management ideals, the comparison to health care becomes less obvious. How can manufacturing cars be like caring for patients? It turns out that every manufacturing element is a production process. Health care is a combination of complex production processes: admitting a patient, performing surgery, or sending out a bill. Each involves thousands of processes, many of them very complex. All involve the concepts of quality, safety, customer satisfaction, staff satisfaction, and cost effectiveness. In health care, failing to deliver in any area not only causes dissatisfaction, but may even lead to patient harm.

Introduction to Lean Principles

In a sequel book on lean, Womack and Jones provided 5 principles of lean production: defining value, value stream, flow, pull, and perfection. For simplification, this chapter will discuss value and value stream together. When improving any process using lean methods, it is important to study that process with respect to each of these five principles.

Defining value is the first step in “leaning” any process. Hence, one first identifies what is valuable within the process, as determined by the customer of the process. In identifying value, waste is automatically identified as that which is not valuable. Since the ultimate customer of any process in health care is the patient, it is important to ask “what would the patient be willing to pay for?” In auto manufacturing, car sales make this apparent. In health care, it has been historically less obvious. Does the process or task being improved change the form, fit, function, or satisfaction of the patient? If not, perhaps it does not add value. Using lean we can actually map out each step of an entire process in order to see the value and waste. This activity is called value stream mapping.

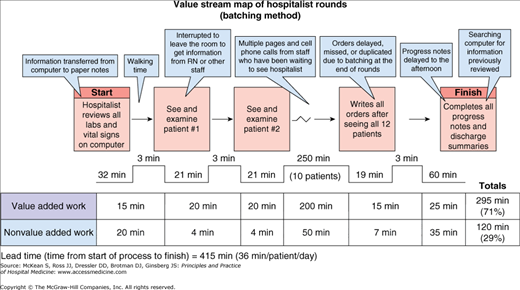

A value stream is a series of specific actions necessary to complete a task or create a product from beginning to end. Value stream maps are created to visually communicate where value and waste occur in any process. Creating a value stream map involves making observations about a process, noting each step and its sequence, and measuring the time it takes for each step to occur (Figure 20-1). In Figure 20-1, note that the products measured are documentation and orders completed on a panel of hospitalized patients. Non-value-added activities are denoted and the time wasted performing these activities is measured. Non-value-added activities will need to be eliminated if the process is to be improved.

Waste can be categorized into 7 types in health care processes:

- Overproduction: Any time a process causes a task to be performed more than necessary, production waste occurs. Examples of overproduction waste include ordering unnecessary labs, delivering 2 lunch trays to the same patient, or administering IV medications when oral medications would have been adequate.

- Time-on-hand: This type of waste refers to waiting. Any time a patient is waiting for a medication, a procedure, or a provider it is considered waste. The hospital rounding example in Figure 20-1 illustrates time-on-hand waste as patients, families, and nurses waiting for the hospitalist to round and write orders. Also, the consultant may be waiting for the hospitalist’s progress note.

- Transportation: Unnecessary transport of people, equipment, or supplies is considered transportation waste. Examples include having to transport a patient to another facility to acquire an MRI or ordering a procedure kit but not using it.

- Processing: This form of waste is associated with unnecessary handling, clerical work, cognitive effort, and time spent working on a process or task. An example of processing waste is seen in Figure 20-1 as the provider copies information from computer screen to paper and then back into a computer-generated progress note. Another example is searching for information that may have already been reviewed earlier in the day.

- Stock on Hand: Excessive inventory is a form of waste. Examples include storing large quantities of expensive medications or other costly supplies for weeks or months before they are used.

- Movement: Here, waste is as simple as a provider having to walk 20 feet to pick up a chart or walking to multiple wards to see patients.

- Defective Products: Any time a process creates a product that is defective, whether it is harmful or not to the patient, it is waste. Providing the wrong dose of a medication, documentation errors, or wrong-site surgery are all examples of defective product waste.

|