Key Clinical Questions

Which patients with urinary tract infections need hospital admission?

When should catheter-associated urinary tract infections be treated?

When is renal imaging indicated?

When should urology consultation be obtained?

What are the appropriate durations of therapy for uncomplicated cystitis, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, and pyelonephritis?

For which patients are follow-up urine cultures indicated after discharge?

Introduction

Urinary tract infections are very common, and account for a significant portion of health care costs. Over half of all women have at least one urinary tract infection (UTI) during their lifetime. In the United States, community-acquired UTIs lead to seven million office visits, one million emergency room visits, over 100,000 hospitalizations, and costs of over $1.6 billion annually. The most common nosocomial infection is catheter-associated UTI, with over one million cases yearly in the United States alone.

Pathophysiology

The vast majority of UTIs arise by the ascending route. Most are caused by strains of Escherichia coli with surface filaments (fimbriae) that bind to urinary epithelium. UTIs occasionally arise from bacteremia. This is especially true of Staphylococcus aureus. Whereas S aureus may cause cystitis in patients with Foley catheters, when patients present with staphylococcal pyelonephritis from the community, beware of the possibility of underlying bacteremia and endocarditis.

Cystitis and pyelonephritis are 5 to 10 times more common in women, due to the short female urethra. In women under the age of 50 years, the major risk factor for UTI is frequency of sexual intercourse, which facilitates passage of bacteria into the bladder. In otherwise healthy women, UTIs are also associated with new sexual partners, reflecting sexual acquisition of uropathogenic strains of E coli, spermicide use, which allows periurethral E coli colonization, and probably genetic factors.

The normal urinary tract has robust anatomic, chemical, and immunologic defenses against infection. These are all negated by the placement of an indwelling urinary catheter. The rate of acquisition of bacteriuria after placement of a urinary catheter is 5% per day. Essentially 100% of patients have bacteriuria one month after placement of an indwelling urinary catheter. Other host abnormalities that predispose to UTI are diabetes mellitus and glucosuria, urinary stasis from obstruction, bladder diverticula, neurologic disease, vesicoureteral reflux, and urinary calculi (Figure 205-1), which may cause local irritation or obstruction and serve as a nidus for persistent infection.

Does the Patient Have a Urinary Tract Infection?

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is very common. It is found in 5% of healthy women, 50% of elderly patients in long-term care facilities, and in most patients with spinal cord injury. Rates of bacteriuria are essentially 100% in patients with chronic indwelling Foley catheters or permanent ureteric stents.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is overtreated. Even the presence of pyuria or cloudy urine by itself does not warrant antibiotic treatment. In most groups studied, treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is associated with increased antibiotic side effects, increased acquisition of antibiotic-resistant organisms, and no long-term benefits. Similarly, treatment of asymptomatic candiduria has not been associated with clinical benefit, and long-term eradication rates are disappointing. Therefore, patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria should not be treated, with three notable exceptions: pregnancy, prior to transurethral resection of the prostate or other urologic procedures involving mucosal bleeding, and preschool children with vesicoureteral reflux. Pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria should receive three to seven days of antibiotic therapy and should have urine cultures repeated later in pregnancy. Screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria have been studied and found not to be helpful in the following groups: premenopausal, nonpregnant women; diabetic women; older persons living in the community; elderly, institutionalized subjects; persons with spinal cord injuries; and patients with chronic indwelling urinary catheters.

The diagnosis of cystitis, or infection of the urinary bladder, is straightforward in women presenting with dysuria, urinary frequency, or both, supported by the finding of positive leukocyte esterase or nitrites on urine dipstick, or pyuria on urine microscopy (defined as at least five white cells per high-power field on a centrifuged specimen). Vaginal irritation or vaginal discharge decreases the likelihood of UTI (Table 205-1); women with these complaints should be assessed for vaginal candidiasis and sexually transmitted diseases.

| Symptom/Finding | Positive LR | Negative LR |

|---|---|---|

| Dysuria present | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| Frequency present | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| Vaginal discharge absent | 3.1 | 0.3 |

| Vaginal irritation absent | 2.7 | 0.2 |

| All of the above | 23 | — |

| Positive urine dipstick (either positive leukocyte esterase or positive nitrates) | 4.2 | 0.3 |

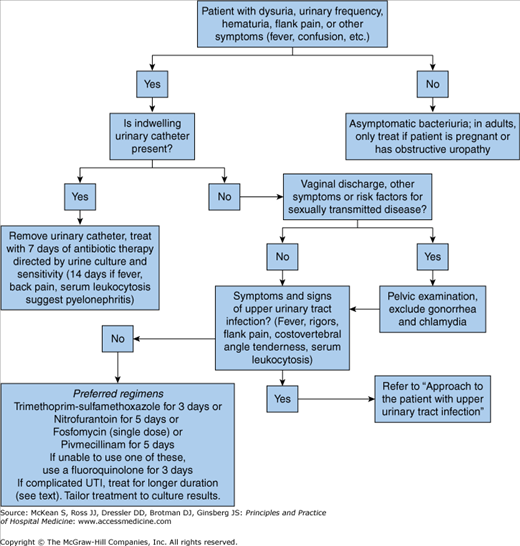

In outpatients, urine cultures need not be checked in most cases of suspected cystitis, but they should be obtained when the diagnosis is unclear and symptoms are atypical, if symptoms persist or relapse after treatment, or if pyelonephritis is suspected (ie, fever or back pain is present). In hospitalized patients, urine cultures should be obtained whenever UTI is suspected. If urine cultures demonstrate < 105 organisms/mL, patients may have bacterial urethritis without cystitis. Gonorrhea or chlamydia should be considered in this setting (Figure 205-2).

In healthy adults, kidney infection is diagnosed when all or most of the following findings are present: oral temperature ≥ 38°C (100.4°F) or rectal temperature ≥ 38.5°C (101.3°F), flank pain or costovertebral angle tenderness, serum leukocytosis, and nitrites or leukocyte esterase on urinary dipstick or pyuria or white cell casts on urine microscopy. These findings are usually, but not invariably, combined with lower tract symptoms of urinary frequency and dysuria. In the geriatric patient, pyelonephritis may present with atypical symptoms, such as malaise, confusion, and vague abdominal pain. Fever is usually lower grade, and flank pain often absent. Pyelonephritis is the most common cause of gram-negative bacteremia. Up to 61% of older adults with pyelonephritis are bacteremic at presentation.

Acute bacterial prostatitis presents with fever, rigors, perineal discomfort, dysuria, and urinary urgency and frequency. The prostate is swollen and often exquisitely tender on examination. Acute prostatitis is generally seen in older men, with E coli as the most common culprit. Urinalysis and urine cultures should be sent. (Urinary cultures after vigorous prostate massage have fallen out of favor, due to concerns regarding provocation of bacteremia.) In the sexually venturesome, Neisseria gonorrhoeae should be entertained, and urethral swabs or urinary gene probes should be sent for gonococcus. Prostatic abscess is not very common, but it should be suspected in men with persistent fever and exquisite prostate tenderness. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and diabetes mellitus are predisposing factors. Pelvic computed tomography (CT) or transrectal ultrasound is diagnostic.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis presents with relapsing dysuria and other urinary symptoms. If perineal discomfort and prostatic tenderness are present, they are usually much milder than in acute prostatitis. E coli and other gram-negatives are usually responsible; rarely, Cryptococcus neoformans or other fungi are involved.

Differential Diagnosis

In women with vaginal discharge, a suggestive sexual history, or a negative urinalysis, pelvic examination should be performed to exclude vaginitis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease, with studies for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Other causes of dysuria in women include atrophic vaginitis, seen in postmenopausal women; interstitial cystitis, an enigmatic disorder most common in younger women; and irritant urethritis from tampons, contraceptive gel, and other substances.

Genitourinary tuberculosis (TB) is rare in the United States. However, it is a valid diagnostic consideration in patients with urinary symptoms, sterile pyuria, calcification of the renal parenchyma, and risk factors for TB exposure. Most patients lack fever, night sweats, or active pulmonary TB. Diagnosis is made on the basis of three early morning urine cultures for acid-fast bacilli. Treatment is similar to that of other forms of TB.

Triage and Hospital Admission

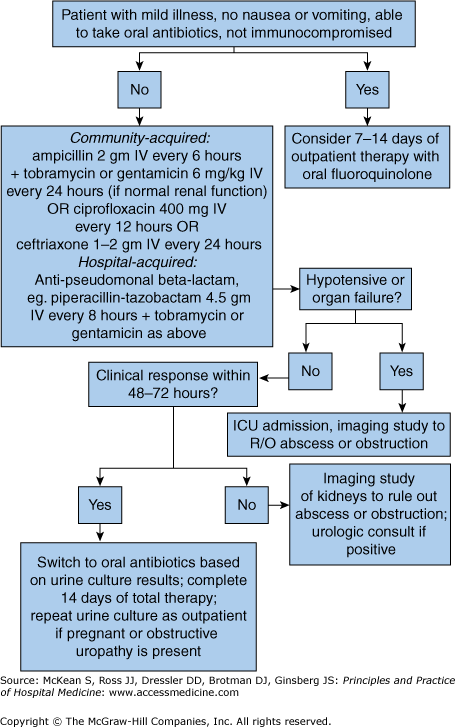

Patients with uncomplicated cystitis (lower tract infection) do not require hospital admission unless there are other medical concerns, such as confusion, dehydration, and inability to take oral antibiotics. Reliable patients with pyelonephritis (UTI) with mild illness, good oral intake, and anatomically normal urinary tracts may be treated as outpatients with oral fluoroquinolones (Figure 205-3). Conversely, patients with pyelonephritis with moderate to severe illness, nausea and vomiting, renal insufficiency or structural abnormalities of the urinary tract, poor social situation, high risk for noncompliance, or who are pregnant require hospital admission and stabilization.

Treatment

According to guidelines issued by the Infectious Diseases Society of America in 2011, the preferred antibiotic regimens for acute uncomplicated cystitis are nitrofurantoin monohydrate/macrocrystals 100 mg twice daily for 5 days, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 160/800 mg (one double-strength tablet) twice daily for 3 days, or fosfomycin 3 gm in a single dose (see below), or pivmecillinam 400 mg twice daily for 5 days.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree