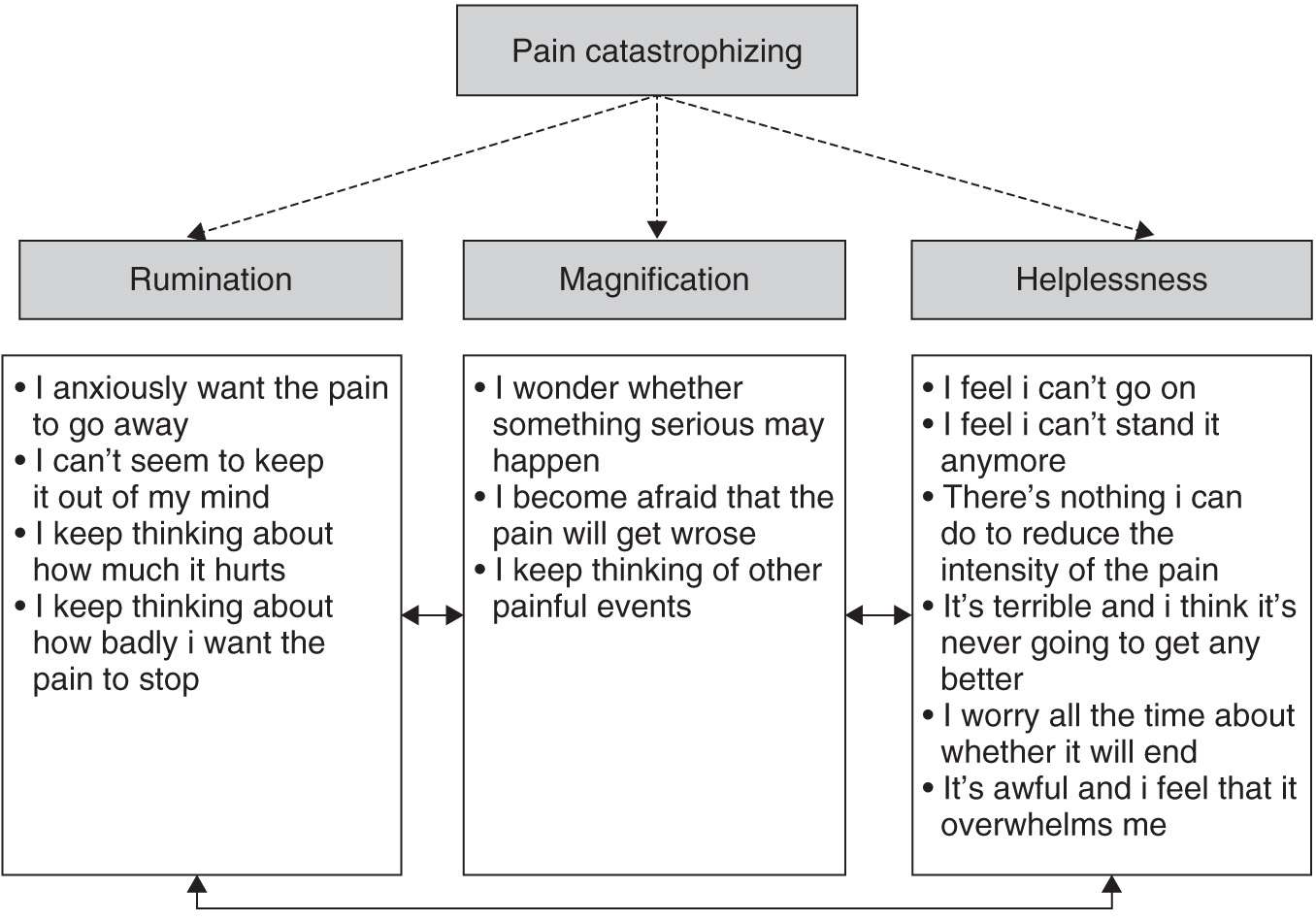

FIGURE 1 A Biopsychosocial Model for UCPPS Outcomes.

DESCRIBING THE SUBJECT

Urologic Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes?

UCPPS are characterized by pelvic pain. Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome/Chronic Prostatitis/Prostate Pain Syndrome (CPPS/CP/PPS) and Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis (BPS/IC) are two such syndromes, with similar symptom profiles and unknown etiologies [22,33]. The shared symptoms include dysuria, pain (perineal, suprapubic, bladder and sexual), and diminished QoL [4]. High prevalence rates exist for CPPS/CP/PPS in men, with symptoms severely impacting patient QoL [26]. Fifty percent of BPS/IC patients report work-related disability [34] and QoL is rated worse than persons’ receiving hemodialysis [12]. CPPS/CP/PPS QoL is comparable to those suffering severe congestive heart failure, diabetes, recent myocardial infarction, unstable angina, hemodialysis dependent end stage renal disease or active Crohn’s disease [20,53]. It is suggested that diminished QoL in UCPPS may partially stem from physician powerlessness within a curative medical framework [13].

Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome/Chronic Prostatitis/Prostate Pain Syndrome

Acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis (i.e., Category 1 & Category 2 respectively) are the best known and least common of the prostatitis syndromes. CPPS/CP/PPS, with or without inflammation, is the third category of prostatitis syndrome with type 3A manifesting noted inflammation, but no evidence of infection. Type 3B, which has no noted inflammation, is regarded as the most common but least understood of the categories and is highlighted in this chapter [25]. The fourth category is asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis in which white blood cells are present in semen but with no associated pain.

CPPS/CP/PPS symptoms can vary [27], with most men reporting acute pain, longstanding persistent pain, or some combination of the two pain features. CP/CPPS/PPS pain is localized mostly to the urogenital regions (perineum, pelvic area, genitalia) [15,36]. Similar to other chronic pain, CPPS/CP/PPS pain does not correspond strongly with medical findings [6] and no medical findings exist for confirmatory diagnosis, making CPPS/CP/PPS a set of symptoms rather than specific disease [23,24]. The National Institutes of Health define CPPS/CP/PPS with pelvic pain for 3 of the previous 6 months, with or without voiding symptoms and with no evidence of uropathogenic bacterial infection [27]. A prostatitis diagnosis is common, accounting for 8% of urology outpatient visits in the United States and 3% in Canada [27]. The North American prevalence of CPPS/CP/PPS symptoms varies between 2–16% [15,36]. Although symptoms peak at 35–65 years [5], they range widely [36]. Research on North American male adolescents are alarming, suggesting as many as 8.3% report CPPS/CP/PPS [46]. Similarly, rates in African adolescents were 13.3% [45].

CPPS/CP/PPS may not routinely remit, with 66% of community-based samples reporting symptoms 1-year later [27], and Urology outpatients showing no drop in pain, disability, or catastrophizing over a multi-year assessment [47]. CPPS/CP/PPS cure successes are rather bleak, with monotherapy methods considered less than optimal [25]. CPPS/CP/PPS QoL is diminished to levels comparable with severe illnesses [21,54] and reviews of QoL outcomes suggest psychiatric disorders strongly coexist [16]. Research supports a biopsychosocial model for CPPS/CP/PPS pain and QoL, with psychosocial risk factors such as pain catastrophizing given a prominent position [29,48].

Catastrophizing in CPPS/CP/PPS

Pain-related “catastrophizing” is a negative, exaggerated cognitive schema engaged in when a patient is in, or anticipates, pain [39]. Catastrophizing is assessed using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale [39], capturing three interrelated factors: rumination, magnification, and helplessness (see Fig. 2). Rumination and magnification tend to be reactionary or proximal cognitive responses to pain, whereas helplessness may develop following ruminative thoughts and or protracted pain. There is little doubt that helplessness about one’s pain and your perceived ability to manage it is associated with feelings of despair.

Catastrophizing is long known in the pain literature as a robust pain predictor in clinical and nonclinical samples [39]. The first CPPS/CP/PPS catastrophizing study found it associated with greater disability, depression, urinary symptoms, and pain [48]. Further, helplessness was the strongest pain predictor, even when urinary symptoms and depression were controlled. Diminished CPPS/CP/PPS mental QoL has also been predicted by greater helplessness and lower support from friends and family, even when demographics, medical status, and other utilized psychosocial variables where controlled [29]. Helplessness is a predominant pain and QoL predictor in CPPS/CP/PPS, commonly reported by patients with longer pain duration (4–7 years) [40]. Interestingly, in the Canadian adolescent sample reporting prevalent CPPS/CP/PPS symptoms, the magnification subscale for catastrophizing (e.g., “I keep thinking of other painful events”) was the lone predictor of diminished QoL after controlling urinary status and pain [46]. Magnification was likely a predictor in these young males due to the relatively acute disease onset and duration these younger males experienced compared to older males.

Evaluations of CPPS/CP/PPS QoL, pain, and psychosocial factors, indicated stability in significant depression and anxiety and that pain, disability, and catastrophizing did not lessen over this 2-year period [47]. Further, catastrophizing was comparable to patients with whiplash [41], BPS/IC [31], and CPPS/CP/PPS [48]. Thus, in the absence of a psychosocial or catastrophizing intervention or a reduction in pain, CPPS/CP/PPS patients are likely to exhibit alarmingly steady negative affect and catastrophic thinking about pain for extended periods. Catastrophizing and its helplessness is most likely a product of feeling unable to affect positive changes in pain.

Social Relations in CPPS/CP/PPS

By investigating spousal support for pain behaviour as buffering agents to poor patient outcomes such as pain or disability, research has provided some appreciable insights in UCPPS and how social support from spouses may be important intervention targets. The supportive spousal coping behaviours are operationalized into couples’ interactions in the form of positive and negative responses to pain behaviour by significant others. Three categories of spousal responses include: solicitous (tries to get me to rest), distracting (tries to get me involved in some activity), and negative (gets angry with me) [14]. When examined in men with CPPS/CP/PPS, solicitous responses from spouses were associated with poorer patient adjustment [8]. Basically, at higher spouse solicitousness, patient pain was more highly associated with disability than at lower levels of solicitousness, indicating that greater solicitousness from a spouse should be avoided [8]. However, these results could also mean that spouses may be responding solicitously as a reaction to the patient’s pain and level of disability, where patients are physically incapable of completing certain tasks, and thus require the help of their spouse. These results may also suggest that spousal responses may be differentially associated with patient adjustment in men and women with chronic pain [7] and may be influenced by a series of inter- and intrapersonal variables [17,18].

Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis

BPS/IC presents with pressure or pain related to the bladder, with at least one or more other urinary symptom, such as urinary urgency or frequency, with no demonstrable infection or other confusable diseases [51]. BPS/IC pain is suprapubically localized, radiating to the groin, vagina, rectum, or sacrum [10], but patients also report multiple pain locations external to the pelvic-abdominal region with greater pain locations associated with worse outcomes [49]. BPS/IC pain may be mild-severe and can be constant, usually associated with bladder filling and voiding. BPS/IC patients also often suffer multiple comorbid abdominal-pelvic region conditions that have pain as a common symptom (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome) [31]. Painful BPS/IC voiding frequency can reach 10–25+ times a day [2], and prevalence is estimated at 3300–11,200/100,000 [2], with symptom onset between 20–40 years [2]. Biomedical treatments that primarily target the bladder are often ineffective [32]. Although men are diagnosed with BPS/IC, it is predominantly diagnosed in women with a female to male ratio of 9:1 [3]. This section focuses on female outcomes.

BPS/IC is associated with clinical phenotypes on the basis of their overlapping symptoms: 1) BPS/IC and no other symptoms, 2) BPS/IC and irritable bowel syndrome only, 3) BPS/IC and fibromyalgia only, 4) BPS/IC and chronic fatigue syndrome only, and multiple associated conditions [31]. Also, as comorbidity of conditions increased, patients presented a localized to systemic illness pattern, which also included greater pain, stress, depression, sleep disturbance, and deteriorating QoL. Both anxiety and catastrophizing remained a concern across such phenotypes [30] and longer symptom durations were associated with phenotypic progression.

In a study of BPS/IC pain mapping, using a full body diagram on which patients endorsed all areas of pain, patients reported more pain than controls in all reported body areas, and four pain phenotypes were created based on increasing counts of body locations [49]. When contrasted, patients reported more body pain locations, along with more pain, urinary symptoms, depression, catastrophizing, and diminished QoL than did the controls. This increasing-pain phenotype model was also found to be associated with poorer psychosocial adjustment and diminished physical QoL, with catastrophizing and scores for low mental QoL remaining stable across all groups [49]. These results suggest that clinicians carefully consider pain location distributions and the potential impact of body pain phenotypes during patient evaluation and treatment.

Catastrophizing in BPS/IC

Some of the earliest patient survey research to examine catastrophizing and BPS/IC showed that patients reporting the highest catastrophizing also reported greater depression, poorer mental health, worse social functioning, and greater pain [35]. Further, catastrophizing, but not age or symptom severity, was related to more severe symptoms for both depression and QoL, suggested similar associations to other pain samples. This finding would be repeated in part by several other future studies. For example, pain experience and catastrophizing have also been tested in a laboratory study examining generalized cutaneous hypersensitivity, which found that catastrophizing was correlated with duration of BPS/IC symptoms and with thresholds to warm stimuli at the T12 dermatome, suggesting habituation to somatic stimuli is impaired in patients. Though one should be cautious drawing conclusions from one study, the physical and psychological differences found in this study could potentially predispose patients with BPS/IC to chronic pain [19].

BPS/IC has also been examined for unique and shared associations between QoL, symptoms, catastrophizing, depression, pain, and sexual functioning [43]. Women recruited from North American centers completed a survey and regressions predicted the unique and combined factor effects on patient QoL. Poor physical QoL was predicted by longer symptom duration and greater pain. However, poor mental QoL was predicted by older age and greater pain catastrophizing, and in particular, the helplessness scale [43]. When considered together, these data indicated that longer duration of symptoms, pain, older age, and helplessness catastrophizing were predictors of poorer QoL over sexual functioning.

Social Relations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree