Ultrasound-Guided Infraclavicular Block

Steven L. Orebaugh

Gerbrand J. Groen

Elilary Montilla Medrano

Paul E. Bigeleisen

Background and indications: Infraclavicular brachial plexus block permits anesthesia of the plexus where most of the major motor and sensory nerves to the arm are anesthetized. In addition, anesthesia of the phrenic nerve with resulTant diaphragmatic paralysis is unlikely.1 Infraclavicular block is used to provide anesthesia and analgesia for procedures involving the distal arm and elbow, wrist, forearm, and hand.

Background and indications: Infraclavicular brachial plexus block permits anesthesia of the plexus where most of the major motor and sensory nerves to the arm are anesthetized. In addition, anesthesia of the phrenic nerve with resulTant diaphragmatic paralysis is unlikely.1 Infraclavicular block is used to provide anesthesia and analgesia for procedures involving the distal arm and elbow, wrist, forearm, and hand.The lateral ultrasound-guided technique has gained popularity in recent years because of its high success rate, low incidence of complications, and ease of performance. Traditionally, practitioners injected local anesthetic into or around the individual cords. The deposition of a single injection of local anesthetic posterior to the axillary artery, however, has been shown to provide reliable anesthesia and is easier to perform than the multiple-injection technique. Once the visualization of local anesthetic spread around the axillary artery is achieved, a 90% success rate is usually accomplished.

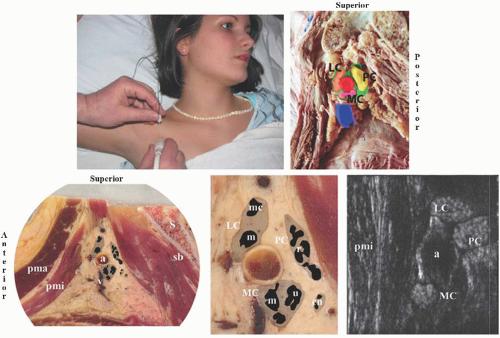

Anatomy: Beneath the clavicle, the cervicoaxillary canal is formed, bounded by the first rib below and the clavicle above. Through this passageway, the vessels and brachial plexus enter the apex of the axilla. Overlying this region, the infraclavicular fossa is formed between the pectoralis major muscle and the deltoid muscle. Needle insertion for infraclavicular block at this point will traverse the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles en route to the plexus (Fig. 19.1). Posterior to the neurovascular bundle is the rib cage and, posteromedially, the pleura and lung.

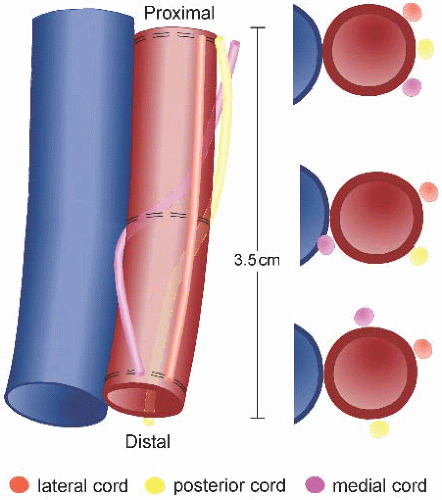

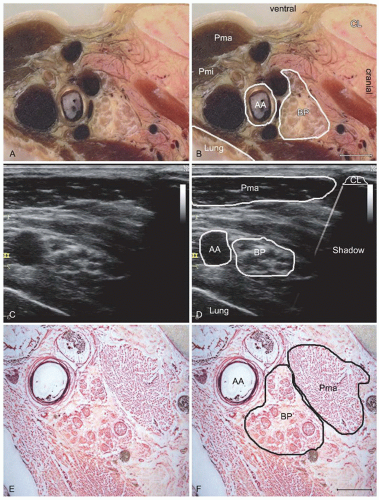

Anatomy: Beneath the clavicle, the cervicoaxillary canal is formed, bounded by the first rib below and the clavicle above. Through this passageway, the vessels and brachial plexus enter the apex of the axilla. Overlying this region, the infraclavicular fossa is formed between the pectoralis major muscle and the deltoid muscle. Needle insertion for infraclavicular block at this point will traverse the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles en route to the plexus (Fig. 19.1). Posterior to the neurovascular bundle is the rib cage and, posteromedially, the pleura and lung.The cords of the brachial plexus are closely aligned with the axillary artery at the infraclavicular region and derive their names from their position with respect to the vessel: posterior, lateral, and medial. Because the plexus spirals around the vessel, this relationship may not be apparent until cords reach the second or third part of the artery (Fig. 19.2). Utilizing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Sauter et al.2 evaluated the relative positions of the cords in volunteers. The authors found that the cords consistently lay within 2.5 cm of the center of the artery, in a range from directly inferior to the vessel to cephaloanterior, arranged circumferentially around the artery. The connective tissue investment, or “sheath,” that defines the space through which the neurovascular bundle passes has multiple interdigitations and septations, which may sequester solutions injected near the nerves (Fig. 19.3).3

The infraclavicular plexus lies deeper than at other sites of the brachial plexus. Wilson et al.4 evaluated the plexus at the pEricoracoid region with MRI and found a mean depth of the plexus elements of 4.2 cm for men and 4.0 cm for women, although the relationship to body

mass index was not explored. On ultrasound, this greater depth is readily appreciated and may require use of a lower frequency transducer setting to provide adequate imaging.5 The cords of the plexus typically appear hyperechoic, or bright, in the infraclavicular region (Fig. 19.1).

mass index was not explored. On ultrasound, this greater depth is readily appreciated and may require use of a lower frequency transducer setting to provide adequate imaging.5 The cords of the plexus typically appear hyperechoic, or bright, in the infraclavicular region (Fig. 19.1).

During ultrasound imaging in the infraclavicular fossa, the structures that appear superficial to the nerves include the skin and subcuTaneous tissues, the pectoralis major and minor muscles, and the clavipectoral fascia (Fig. 19.1). Deep to this fascia, the second part of the axillary artery and the axillary vein are apparent. The artery lies cephalad to the vein. The vein is usually compressible, even at this depth. The hyperechoic cords of the plexus lie in close approximation to the artery, typically reflecting their named positions (Fig. 19.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree