Key Clinical Questions

When should tuberculosis be suspected in the inpatient setting?

What diagnostic testing should be performed in patients with suspected tuberculosis?

What precautions are necessary for patients with possible tuberculosis? When may they be discontinued?

What treatment regimen should be begun for patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis? What monitoring is appropriate in patients being treated for tuberculosis?

Introduction

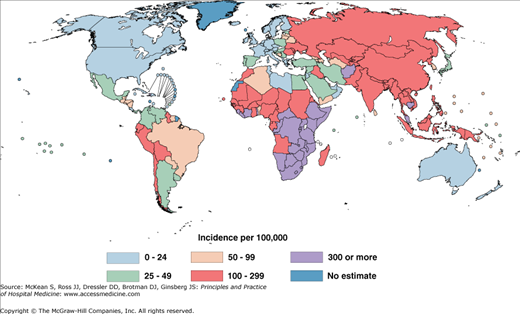

A global pandemic of tuberculosis (TB) that began three centuries ago continues today. According to estimates from the World Health Organization, 14 million people had active TB in 2009, including 9.4 million new cases, with 1.7 million deaths. The ongoing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic continues to fuel the spread of TB; 12% of patients with the disease are HIV positive. The incidence of TB is highest in Asia, Africa, Latin America, Russia, and Eastern Europe (Figure 204-1). Rates are substantially lower in North America and Western Europe, where TB is increasingly a disease of the foreign born. Other groups in developed nations with a high incidence of the disease include homeless persons, injection drug users, incarcerated persons, and some aboriginal populations. Another group at risk in developed nations is the elderly. Rates of TB in the developed world 50 years ago were similar to rates in developing countries today. Older patients born and raised in developed nations therefore have a higher likelihood of developing active TB than younger patients, due to the risk of late reactivation of latent infection.

As TB in the developed world has become uncommon, the diagnosis is often overlooked, even when in retrospect it should have been fairly apparent. Unfortunately, because pulmonary TB may be highly contagious, delays in diagnosis may have disastrous implications not only for the patient, but also for family, friends, and other close contacts, including health care workers.

Pathophysiology

Tuberculosis is caused almost exclusively by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Rarely, it is caused by the related organism Mycobacterium bovis, acquired from infected cattle or contaminated milk products. M tuberculosis is transmitted almost exclusively through the respiratory route by microscopic droplet nuclei. These particles are small enough to remain airborne for long periods of time and to be inhaled directly into the terminal alveoli, typically in the lower lung zones. Droplet nuclei are produced when a patient with pulmonary TB speaks, coughs, or sneezes. Rarely, they are produced from nonpulmonary sources, such as irrigation of TB-infected areas during surgery, during dressing changes of draining wounds, or while emptying of containers of infectious fluid.

M tuberculosis has adapted to survive within alveolar macrophages, the cells one would normally expect to eradicate it. Within the macrophage, the organism travels to the mediastinal lymph nodes, then disseminates throughout the body via the bloodstream, with more vascular areas receiving more organisms. Microscopic foci of live bacteria are thus deposited throughout the body, including the lung apices. Several weeks after infection, the cellular immune system walls off the bacteria in granulomas. Granulomas are not static structures; the organisms within them are alive, albeit dormant, and the cells forming the granuloma constantly turn over. At this stage, the infected individual has what is referred to as latent tuberculosis infection. Patients with latent infection are neither ill nor infectious to others. Roughly 85% to 90% of otherwise healthy individuals in this state never develop symptoms throughout their lifetime, despite ongoing infection. Of the 10% to 15% who do go on to develop symptoms, most do so within the first few years of becoming infected. Once symptoms have developed, the patient is referred to as having active tuberculosis. Although there is a predilection for disease to develop in the apices of the lungs, a large minority of patients will develop symptoms outside the lungs. Commonly involved extrapulmonary sites include regional lymph nodes, pleura, spine, bones and joints, and meninges. Patients with certain underlying medical conditions or receiving immunosuppressive therapy are at high risk of developing active disease if infected (Table 204-1).

| Factor | Relative Risk/Odds |

|---|---|

| Recent infection (< 1 year) | 12.9 |

| Fibrotic lesions (spontaneously healed) | 2–20 |

| Comorbidity | |

| HIV infection | 100 |

| Silicosis | 30 |

| Chronic renal failure/hemodialysis | 10–25 |

| Diabetes | 2–4 |

| Intravenous drug use | 10–30 |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 10 |

| Gastrectomy | 2–5 |

| Jejunoileal bypass | 30–60 |

| Posttransplantation period (renal, cardiac) | 20–70 |

| Malnutrition and severe underweight | 2 |

|

Clinical Presentation

Unfortunately, the symptoms of active TB are often vague and nonspecific, sometimes leading to initial misdiagnosis. It is common for a TB clinic to see patients who were initially investigated for malignancy. Patients typically report having had symptoms for weeks to months prior to being diagnosed. In some cases, symptom onset can be so gradual that patients realize the extent of their illness only after they have improved with treatment. Early cases can be entirely asymptomatic, having been detected on a chest radiograph performed for other reasons. Rarely, patients present with acute symptoms, mimicking more typical bacterial infections, or they may develop disseminated (miliary) TB, with a rapidly progressive febrile wasting illness, with or without pulmonary complaints.

Constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, fatigue, fever, night sweats, and rigors tend to be more common with pulmonary and pleural disease, together with a worsening productive cough. Although massive hemoptysis was once common in the preantibiotic era, hemoptysis is rare and, if present, is typically minor. Constitutional symptoms may be absent in cases of extrapulmonary TB, especially in patients with disease confined to lymph nodes. Tuberculous lymphadenitis is the most common form of extrapulmonary TB. It usually presents as painless swelling of the posterior cervical or supraclavicular lymph nodes, although patients may also develop lymph node tenderness and fistula formation. Pleural tuberculosis may present with fever, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain if the effusion is sizable enough. Genitourinary tuberculosis may present with dysuria, urinary frequency, flank pain, and hematuria, although it may also often be asymptomatic until hydronephrosis and severe kidney damage have occurred. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott disease) most often presents with back pain from infection of the thoracic or lumbar spine, often with paravertebral cold abscesses involving the psoas muscle. Tuberculous meningitis presents as a subacute or chronic basilar meningitis, often with cranial nerve palsies; central nervous system (CNS) involvement may also produce a tuberculoma, leading to seizures and focal neurologic deficits. Tuberculous peritonitis presents with abdominal pain and ascites, with diffuse peritoneal implants on abdominal imaging; it is often mistaken for ovarian cancer or other intraabdominal malignancies.

Diagnosis

The greatest obstacle to the diagnosis of tuberculosis is the failure to consider it in the differential diagnosis. Patients with pulmonary TB may seek medical attention several times before the diagnosis is considered. Patients may be treated with fluoroquinolone antibiotics for presumed community-acquired pneumonia, resulting in temporary improvement that may further delay the diagnosis and lead to potentially more contacts becoming infected. Patients with extrapulmonary TB often undergo diagnostic tests focused on detecting malignancy rather than TB. For example, patients with tuberculous lymphadenitis may have excisional lymph node biopsies to exclude lymphoma, without tissue being sent for mycobacterial culture. TB should be clinically suspected in patients who present with compatible symptoms and have epidemiologic risk factors for infection or progression to active disease. For example, pulmonary TB should be considered in a patient originally from an endemic area with chronic renal failure and a new cough. Once suspected, the diagnosis can usually be confirmed with appropriate testing without great difficulty, although there are exceptions as mentioned below.

Basic chest radiography is useful in diagnosing pulmonary TB, especially if cavities (Figure 204-2) or evidence of prior TB infection is present, such as apical scarring or pleural thickening. Rarely, tiny miliary nodules are seen (Figure 204-3). Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are more appropriate for diagnosing spinal TB, meningitis, pericarditis, and TB of deep organs or organ spaces. Although radiographic findings can be typical for TB, they are rarely pathognomonic; hence the collection of fluid or tissue for histology and mycobacterial culture is essential to confirm the diagnosis.