4 Treating the discs

The discs act as flexible cushions between the spinal vertebra during mechanical shear and loading, cushioning the spine and giving it flexibility. Discs have an inner gel-like nucleus surrounded by an outer covering, the annulus fibrosus, wrapped in 13 concentric laminated bands around the nucleus, not unlike a jelly doughnut wrapped around its jam filling. The well-innervated disc annulus has no vascular supply and receives its nutrients by diffusion from the vertebral body vascular supply where it attaches to the end plates (White 1978). The disc is an osmotic system sensitive to load, pressure and concentration of proteoglycans that lives from motion (Kraemer 1995).

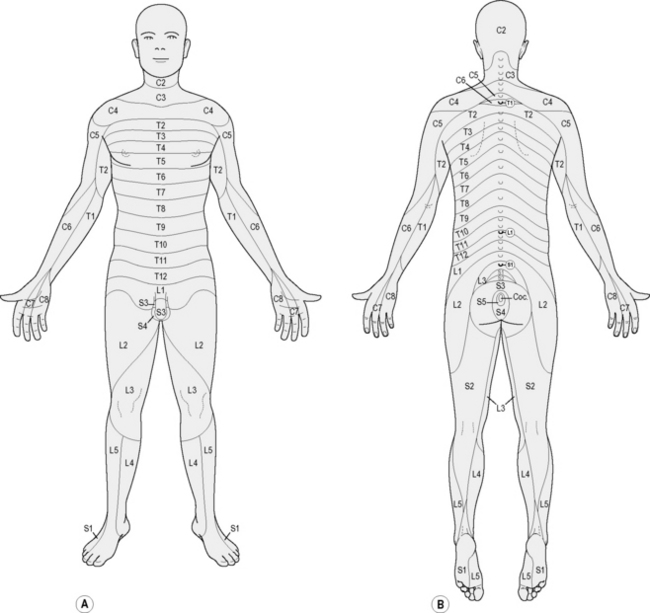

The outer three annular layers of the healthy disc are innervated by small myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers from the dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic trunks from multiple spinal levels. A disc at one spinal level may receive innervation from three or more spinal levels which means that inter-neurons in the cord are also involved. The vertebral end plate is as well innervated as the disc annulus suggesting that the end plate is an important source of discogenic pain (Lotz 2006).

The muscles at the spine stabilize the segment and protect the disc and the joint during movement. If the muscles are not effective the joint moves too much, the annulus is overstressed and the rate of degeneration increases: “… degeneration occurs as the result of imbalance of both static and dynamic spinal stabilizers. The disc degeneration that occurs is characterized by increased local inflammation and increased apoptosis of intervertebral disc cells” (Wang 2006).

The disc nucleus is rich in phospholipase A2, a strongly proinflammatory substance that is very toxic and damaging to nerves (Olmarker 1993, 1995, Ozaktay 1995, 1998). When the disc bulges or ruptures the fragments of the nucleus expand from hydration when they are outside annular containment. The disc fragments create inflammatory damage to the nerves, the disc annulus and the surrounding tissues which is compounded by the immune system inflammatory response to a foreign body in the epidural space.

Degeneration is an inevitable response to mechanical loading and shear during repetitive motion or constant static loading as the spine ages. Studies have shown increases in IL-1, IL-6, TNFα and PGE2 in injured discs. TNFα stimulates nerve growth factor and causes pain sensitive nerves to infiltrate the outer layers of the disc annulus and become sensitized. The degenerative process in the discs is complex and characterized by inflammation, loss of water and elasticity, tearing, scarring and disorganization of annular fibers, infiltration of nerves into the degenerated annulus and end plate tissues and dehydration and fragmentation of the nucleus (Kang 1996).

Pathologic degeneration may be a chronic ineffective healing response consisting of ongoing accumulation of tissue damage in the end plate and disc annulus, inflammation, neo-innervation and nociceptor sensitization. Physiologic degeneration on the other hand may be an adaptation to loading over time, without accumulation of peripheral damage and thus having no appreciable inflammatory or nociceptive component (Lotz 2006). Patients with genetic predisposition to increased inflammation have increased degenerative response to activities that compromise disc health (Solovieva 2004). This genetic predisposition, when combined with environmental factors can create enhanced inflammatory response and may explain the difference between two patients with identical spinal imaging showing disc degeneration when one patient has tremendous pain symptoms and one has no pain at all.

Medical treatment for disc related injuries and pain includes pain medication, steroids to reduce the inflammatory response, physical therapy, exercises to stabilize the spine and move the disc fragment away from the nerve root as recommended by McKenzie (2006) and ultimately surgery. Epidural steroid and “caine” class anesthetic injections are used to reduce the nerve pain and inflammation and to keep the patient comfortable while the disc heals. Cauda equina symptoms, such as loss of bowel or bladder function, and severe motor weakness are indications for open spinal surgery without delay.

Ultimately, if the pain can be managed and the surgery is put off long enough the symptoms resolve on their own and fewer than 10% of patients presenting with discogenic and radicular pain require surgery. Only 0.25%, one quarter of one percent, of individuals with “back problems” requires some form of surgery (Kraemer 1995).

Most surgeries are performed to provide pain relief for patients in the acute phase of disc inflammation. FSM has been shown to be effective in reducing neuropathic pain (Chapter 3) and in reducing IL-1, IL-6, TNFα and COX and LOX mediated inflammation, all of which have been implicated in discogenic pain. If FSM can be used to reduce inflammation and pain along with exercise therapies in the 99.75% of back pain patients who do not require surgery, more patients can recover function and avoid surgery and its complications. There are numerous case reports in which FSM treatment has done exactly this. The responses are consistent, predictable, reproducible and very encouraging to both patients and clinicians treating this difficult patient population.

Diagnosing the disc

Cervical discogenic pain may present as neck, shoulder and arm pain or midscapular pain. The classic diagram (Fig. 4.3) published by Cloward describes the midscapular referred pain areas for the cervical discs. The patient with a cervical disc injury may present only with midscapular pain and shoulder pain (Cloward 1959). Treating the shoulder or the midscapular area will be unsatisfactory and only treatment aimed at the cervical disc will relieve the symptoms.

History questions

• What sorts of things were you doing in the days or weeks just before the pain started?

Look for activities that require flexion or combined flexion and rotation such as golf or tennis, yard work, laying floor coverings, painting, or moving.

Look for activities that require flexion or combined flexion and rotation such as golf or tennis, yard work, laying floor coverings, painting, or moving.• Were you lifting, leaning forward while using a keyboard, sitting, driving or bending over for long periods?

• Did you have any sort of trauma such as a fall or traffic accident?

Side impact accident force vectors put the discs at special risk especially if the spine is in rotation at the traumatized segment at the time of impact.

Side impact accident force vectors put the discs at special risk especially if the spine is in rotation at the traumatized segment at the time of impact.• Were you in one flexed or rotated position without moving for a prolonged period of time?

One patient fell asleep for 6 hours sitting up with his head tilted over to one side compressing the disc annulus and causing a small disc bulge that was read as “normal” on an MRI. The ensuing severe neck, shoulder and arm pain was clearly disc and nerve related but he waited 2 years for a diagnosis because his physicians didn’t connect the mechanism of injury with the vulnerability of the discs to compression, rotation, connective tissue creep and shear. In 2 years no one had done a sensory examination.

One patient fell asleep for 6 hours sitting up with his head tilted over to one side compressing the disc annulus and causing a small disc bulge that was read as “normal” on an MRI. The ensuing severe neck, shoulder and arm pain was clearly disc and nerve related but he waited 2 years for a diagnosis because his physicians didn’t connect the mechanism of injury with the vulnerability of the discs to compression, rotation, connective tissue creep and shear. In 2 years no one had done a sensory examination.• What do you do for a living?

Truck drivers, heavy equipment operators or workers who use equipment that vibrates while they are sitting have accelerated rates of degeneration in the discs and facets. The precipitating injury that is the “final straw” may seem minor but it will always involve axial compression, flexion or flexion and rotation. The most commonly degenerated discs are at L5–S1 but any lumbar disc can be at risk.

Truck drivers, heavy equipment operators or workers who use equipment that vibrates while they are sitting have accelerated rates of degeneration in the discs and facets. The precipitating injury that is the “final straw” may seem minor but it will always involve axial compression, flexion or flexion and rotation. The most commonly degenerated discs are at L5–S1 but any lumbar disc can be at risk. Data processors, secretaries, dental assistants and dentists, watch repairmen and violinists work in positions that put the neck into chronic prolonged flexion and rotation. These professions come to mind but any profession with similar biomechanical challenges is at risk for discogenic disease.

Data processors, secretaries, dental assistants and dentists, watch repairmen and violinists work in positions that put the neck into chronic prolonged flexion and rotation. These professions come to mind but any profession with similar biomechanical challenges is at risk for discogenic disease.• What do you do for fun or do at home?

People who work in the yard or garden and who pull weeds by hand, who lay stones, or who dig holes or trenches with picks or shovels subject the spine to intense compressive forces with the neck and low back in a flexed position. People who work on cars often find themselves lifting heavy loads in awkward positions or working in one flexed position for prolonged periods of time. Some sports such as golf or tennis exert ballistic rotational forces on the discs that create chronic micro-injuries and eventually tissue failure.

People who work in the yard or garden and who pull weeds by hand, who lay stones, or who dig holes or trenches with picks or shovels subject the spine to intense compressive forces with the neck and low back in a flexed position. People who work on cars often find themselves lifting heavy loads in awkward positions or working in one flexed position for prolonged periods of time. Some sports such as golf or tennis exert ballistic rotational forces on the discs that create chronic micro-injuries and eventually tissue failure.Nerve pain patterns

• C3: refers pain to the slope of the neck along the trapezius muscle and the patient may say they cannot tolerate a necklace or any clothing touching the neck

• C4: refers pain to the point of the shoulder and can mimic shoulder joint injury

• C5: refers pain into the upper arm

• C6: refers pain to the thumb and the lateral elbow

• C7: nerve root refers to the medial elbow

• Thoracic nerve roots: refer pain onto the chest or abdomen depending on the level affected

• L2: Groin, hip or upper thigh

• L5: Lateral calf, great toe and area between the first and second toe

• S1: Heel and lateral edge of the foot

• Pudendal nerve: refers pain to the pelvis, genitals and groin through S2, S3, S4.

Muscle pain patterns

Muscle in the shoulder girdle is innervated by the C5 or C6 nerve roots. The nerve irritation creates taut muscles and the taut muscles may develop myofascial trigger points which have their own pain patterns referring into the arms and hands. The practitioner is referred to The Trigger Point Manual for complete listing of trigger point referral areas (Travell 1983).

Every muscle in the hip and low back is innervated by branches of the L3 nerve root. Disc related nerve irritation causes the muscles to become taut and eventually to develop myofascial trigger points. The trigger point referred pain patterns overlap the referred pain patterns from the discs and nerves and can complicate the diagnostic challenge. In some cases the trigger points are the only symptom and the perpetuating factor is the disc injury and inflammation (Travell 1992). Treating the muscle gives temporary relief and only treatment aimed at the disc will provide lasting improvement.

What makes it better – What makes it worse?

Flexion / combined flexion and rotation

The inability to tolerate flexion postures is diagnostic of disc injuries. The patient may complain

specifically that the pain is worse when driving a car because the seats put the lumbar spine into flexion and the legs are extended while using the pedals. This position creates flexion pressure on the discs, and stretches the sciatic nerve causing pain in the foot, leg or hip.

Physical examination

The disc can be directly challenged by maneuvers that physically compress it or stress it in the direction of lesion. Cervical discs can be evaluated by gently pressing on the top of the head and loading the discs in axial compression. If a disc annulus is compromised the maneuver will cause pain between the scapulae (Cloward 1959) and may increase pain in the affected dermatome.

Muscle testing

Muscle testing is done by isolating the involved muscle and gently loading it to determine strength. If the muscle “locks and holds” when loaded it has full strength (+5/5). If it contracts but doesn’t “hold” against testing pressure it is somewhat weak (+4/5). If it is unable to hold against any pressure it is weak (+3/5). And if it is unable to lift against gravity it is significantly weak (+2/5). The reader is referred to Hoppenfeld (1976) or a similar physical examination text for a more complete description of muscle testing and evaluation.

More than one diagnosis

As always the patient is entitled to more than one diagnosis. FSM practitioners have tools to treat each of these conditions and the only challenge is figuring out which to treat first in any given patient or whether to treat them all simultaneously (see Chapters 5, 6, 7, 11).

Treating spinal discs

• The patient must be hydrated to benefit from microcurrent treatment.

• Hydrated means 1 to 2 quarts of water consumed in the 2 to 4 hours preceding treatment.

• Athletes and patients with more muscle mass seem to need more water than the average patient.

• The elderly tend to be chronically dehydrated and may need to hydrate for several days prior to treatment in addition to the water consumed on the day of treatment.

• DO NOT accept the statement, “I drink lots of water”

• ASK “How much water, and in what form, did you drink today before you came in?”

• Coffee, caffeinated tea, carbonated cola beverages do not count as water.

Channel B: tissue frequencies

The well innervated disc annulus is the most pain sensitive and most easily injured portion of the disc. It consists of coiled layers of sturdy connective tissue wrapped around the gel like nucleus. This tissue frequency responds best to treatment.

The well innervated disc annulus is the most pain sensitive and most easily injured portion of the disc. It consists of coiled layers of sturdy connective tissue wrapped around the gel like nucleus. This tissue frequency responds best to treatment. The gel like disc nucleus fills the center of the disc and absorbs water to become a cushion for the vertebral bodies in the spine. It is very high in PLA2 and very inflammatory.

The gel like disc nucleus fills the center of the disc and absorbs water to become a cushion for the vertebral bodies in the spine. It is very high in PLA2 and very inflammatory.• Dermatomal or Peripheral Nerve: ___ / 396