CHAPTER 158

Traumatic Tattoos and Abrasions

Presentation

The patient has fallen onto a coarse surface, such as a blacktop or macadam road. Most frequently, the skin of the face, forehead, chin, hands, and knees is abraded. When pigmented foreign particles are impregnated within the dermis, tattooing will occur. An explosive form of tattooing can also be seen with the use of firecrackers, firearms, and homemade bombs.

What To Do:

Cleanse the wound with tap water, normal saline, or other products (e.g., poloxamer 188 or Shur Clens,) that are not destructive to epidermal and dermal skin cells.

Cleanse the wound with tap water, normal saline, or other products (e.g., poloxamer 188 or Shur Clens,) that are not destructive to epidermal and dermal skin cells.

Provide tetanus prophylaxis (see Appendix H).

Provide tetanus prophylaxis (see Appendix H).

With explosive tattooing, particles are generally deeply embedded and will require plastic surgery consultation. Any particles embedded in the dermis may become permanent tattoos. Abrasions that are large (more than several square centimeters), deep into the dermis, or into the subcutaneous tissues may also require consultation and/or skin grafts.

With explosive tattooing, particles are generally deeply embedded and will require plastic surgery consultation. Any particles embedded in the dermis may become permanent tattoos. Abrasions that are large (more than several square centimeters), deep into the dermis, or into the subcutaneous tissues may also require consultation and/or skin grafts.

With superficial abrasions and abrasive tattooing, the area can usually be adequately anesthetized by applying 2% viscous lidocaine, 4% lidocaine solution, or gauze soaked with LET (lidocaine 4%, epinephrine 1:2000, tetracaine 0.5%) directly onto the wound for approximately 5 minutes.

With superficial abrasions and abrasive tattooing, the area can usually be adequately anesthetized by applying 2% viscous lidocaine, 4% lidocaine solution, or gauze soaked with LET (lidocaine 4%, epinephrine 1:2000, tetracaine 0.5%) directly onto the wound for approximately 5 minutes.

If this is not successful, locally infiltrate with buffered 1% or 2% lidocaine using a 25- to 27-gauge, 1½- to 3-inch spinal needle for large areas. Before infiltrating painful local anesthetics over large areas, consider parenteral opioid analgesia, or even procedural sedation.

If this is not successful, locally infiltrate with buffered 1% or 2% lidocaine using a 25- to 27-gauge, 1½- to 3-inch spinal needle for large areas. Before infiltrating painful local anesthetics over large areas, consider parenteral opioid analgesia, or even procedural sedation.

For wounds containing tar or grease, application of bacitracin ointment before cleaning will help dissolve and loosen these contaminants.

For wounds containing tar or grease, application of bacitracin ointment before cleaning will help dissolve and loosen these contaminants.

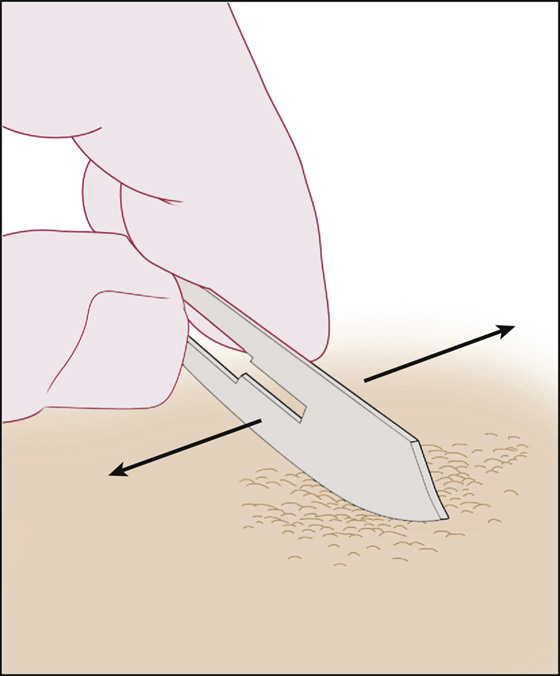

The wound should then be cleaned with a gauze sponge with saline or 1% povidone-iodine (Betadine solution). For heavily contaminated wounds, use a surgical scrub brush, even one impregnated with chlorhexidine (as long as the chlorhexidine is rinsed thoroughly from the injured areas, because, over time, it is associated with mild tissue toxicity in wounds). If there is concern for tissue toxicity with povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine, consider using a poloxamer 188–impregnated sponge. When entrapped material remains, use a sterile stiff toothbrush to clean the wound or use the side of a No. 10 or 15 scalpel blade to scrape away any debris (Figure 158-1). While working, continuously cleanse the wound surface with gauze soaked in normal saline to reveal any additional foreign particles. Large granules may be removed with the tip of the scalpel blade.

The wound should then be cleaned with a gauze sponge with saline or 1% povidone-iodine (Betadine solution). For heavily contaminated wounds, use a surgical scrub brush, even one impregnated with chlorhexidine (as long as the chlorhexidine is rinsed thoroughly from the injured areas, because, over time, it is associated with mild tissue toxicity in wounds). If there is concern for tissue toxicity with povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine, consider using a poloxamer 188–impregnated sponge. When entrapped material remains, use a sterile stiff toothbrush to clean the wound or use the side of a No. 10 or 15 scalpel blade to scrape away any debris (Figure 158-1). While working, continuously cleanse the wound surface with gauze soaked in normal saline to reveal any additional foreign particles. Large granules may be removed with the tip of the scalpel blade.

Figure 158-1 Dermabrasion with a No. 10 scalpel blade.

Small wounds should be left open and bacitracin ointment or petroleum jelly applied. The patient should be instructed to gently wash (not scrub) the area two or three times per day and continue applying the ointment until the wound becomes dry and comfortable under a new coat of epithelium, which may require a few weeks. Use of ointments over excessively long periods can lead to maceration of tissue, rather than normal healing.

Small wounds should be left open and bacitracin ointment or petroleum jelly applied. The patient should be instructed to gently wash (not scrub) the area two or three times per day and continue applying the ointment until the wound becomes dry and comfortable under a new coat of epithelium, which may require a few weeks. Use of ointments over excessively long periods can lead to maceration of tissue, rather than normal healing.

When a larger wound has been adequately cleansed, one alternative is to use a closed dressing with Adaptic (oil emulsion) gauze, ointment, and a scheduled dressing change within 2 to 3 days.

When a larger wound has been adequately cleansed, one alternative is to use a closed dressing with Adaptic (oil emulsion) gauze, ointment, and a scheduled dressing change within 2 to 3 days.

What Not To Do:

Do not ignore embedded particles. If they cannot be completely removed, inform the patient about the probability of permanent tattooing and arrange a plastic surgery consultation.

Do not ignore embedded particles. If they cannot be completely removed, inform the patient about the probability of permanent tattooing and arrange a plastic surgery consultation.

Discussion

The technique of tattooing involves painting pigment on the skin and then injecting it through the epidermis into the dermis with a needle. As the epidermis heals, the pigment particles are ingested by macrophages and permanently bound into the dermis. The best approach in managing patients with traumatic tattoos is the immediate removal of particles during the initial care. Immediate care is important because once the particles are embedded and healing is complete, it becomes much more difficult to remove them. It is advisable for a patient to protect a dermabraded area from sunlight for approximately 1 year to minimize excessive melanin pigmentation of the site.

Traditionally, destructive methods of delayed tattoo removal, including surgical excision, dermabrasion, cryosurgery, and chemical peels, have all produced disappointing cosmetic results, with unacceptably high rates of scarring. With the development of Q-switched laser technology, however, tattoo removal has become much safer and more reliable, and the tattoos typically clear within a few laser treatments. The wavelengths emitted by these lasers are absorbed by pigmented particles, breaking them into smaller pieces that are less visible. The smaller particles are then taken up by inflammatory cells and eliminated by the lymphatic system or transepidermally. Tattoo removal with Q-switched lasers is moderately painful; a local anesthetic may be necessary. Transient or permanent hypopigmentation can occur, especially in dark-skinned patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree