(1)

Trauma and Critical Care, R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, Baltimore, MD, USA

Keywords

KidneyUreterBladderBlunt traumaPenetrating traumaCystogramComputed tomography (CT)CT cystogramPercutaneous nephrostomyStentFoley catheter drainageSurgical explorationGunshot woundsGrading scalesIntroduction

Trauma to the genitourinary (GU) tract affects 10 % of patients with abdominal trauma [1] and 0.5–3.1 % of all trauma patients [2–4]. Although not often the cause of significant shock, GU trauma frequently occurs in the setting of multi-trauma and may be overlooked, causing significant morbidity [5]. Blunt trauma accounts for 80–90 % of GU injuries [6, 7]; however, in an urban setting, penetrating trauma may cause up to 20 % of GU trauma [8]. In contrast, over three-fourths of the cases requiring surgical exploration are caused by penetrating injury [7]. In blunt trauma, 43 % of GU injuries are to the kidney, 9 % to the bladder, and 47 % to the external genitalia. Ureteral injuries are relatively rare in blunt trauma [2] and account for less than 1 % of all urologic trauma [5].

Grading of Renal Injuries

The organ injury scale for renal trauma was first published in 1989 by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) (Table 15.1) [9]. A proposed revision to the AAST renal injury grading scale recommended designation of all collecting system injuries and segmental vascular injuries as Grade IV (Fig. 15.1) and limited the designation of Grade V to main renal artery and vein injuries [7]; however, this revision was not formally adopted.

Grade I | Contusion: microscopic or gross hematuria, urologic studies normal |

Hematoma: subcapsular, nonexpanding without parenchymal laceration | |

Grade II | Hematoma: nonexpanding perirenal hematoma confined to renal retroperitoneum |

Laceration: <1 cm parenchymal depth of renal cortex without urinary extravasation | |

Grade III | Laceration: >1 cm parenchymal depth of renal cortex without collecting system rupture or urinary extravasation |

Grade IV | Laceration: parenchymal laceration extending through renal cortex, medulla, and collecting system |

Vascular: main renal artery or vein injury with contained hemorrhage | |

Grade V | Laceration: completely shattered kidney |

Vascular: avulsion of renal hilum which devascularizes kidney |

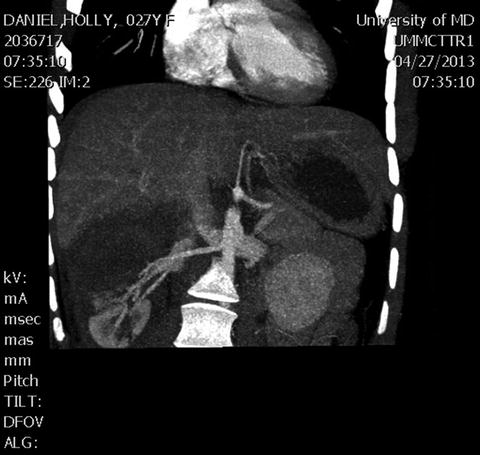

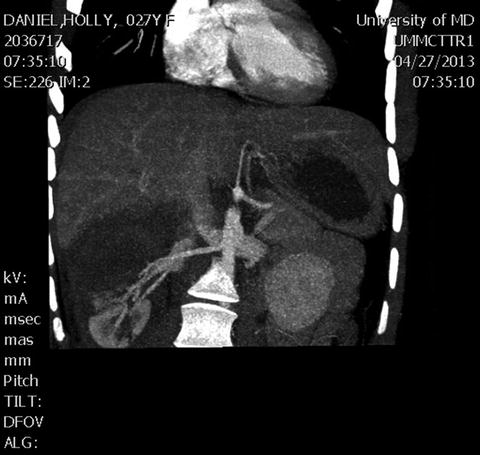

Fig. 15.1

Grade IV blunt right kidney injury with approximately 60 % devascularization.

Imaging

Initial evaluation by computed tomography (CT) scan is indicated in cases of blunt and penetrating trauma when the patient is hemodynamically stable. For blunt trauma with injuries to the pelvic arch, it is important to look for blood at the urethral meatus. If there is no blood at the meatus, placement of a Foley catheter may be attempted. When gross hematuria is identified, then a cystogram or CT cystogram is indicated to look for injury to the bladder. Similarly, for penetrating injuries to the pelvis and suprapubic region, cystography is indicated in stable patients. CT cystogram requires instillation of 350 ml of contrast into the bladder, then clamping of the Foley for the scan. A routine CT with passive filling of the bladder is not adequate to exclude bladder injury [10–12]. When blood is present at the urethral meatus, a retrograde urethrogram must be performed prior to Foley catheter placement.

Reimaging of renal injuries should not be performed routinely but is indicated for evaluation of sepsis, flank pain, decreased hemoglobin, or persistent hematuria. Scheduled reimaging may be considered for early detection of complications in Grade V injuries [13].

Management of Renal Injuries

Grade I–III renal injuries may be observed. Grade IV injuries require intervention by angiography or surgical exploration when there is hemodynamic instability or vascular extravasation. Grade V injuries require surgical exploration in most cases (Fig. 15.2). Not all collecting system injuries require surgical repair, and management with percutaneous nephrostomy, stenting, and Foley catheter may be preferred, particularly if there is no other indication for laparotomy. Figure 15.3 illustrates a penetrating injury to the collecting system that was managed with nephrostomy and stenting.

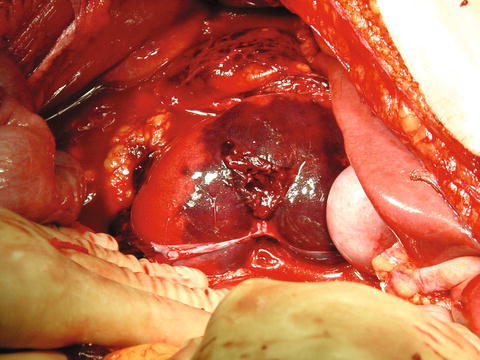

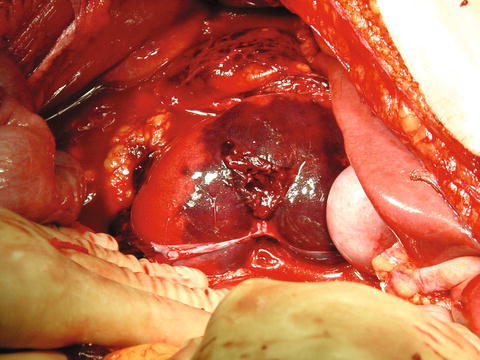

Fig. 15.2

Nephrectomy specimen demonstrating Grade V laceration through renal hilum.

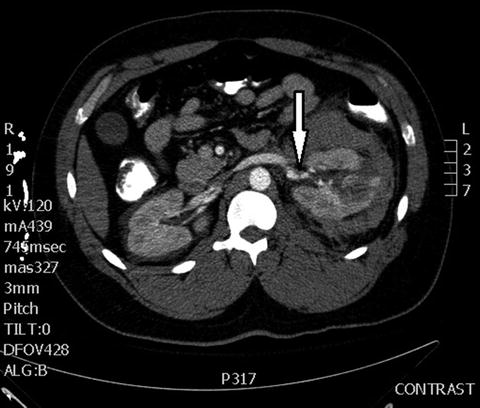

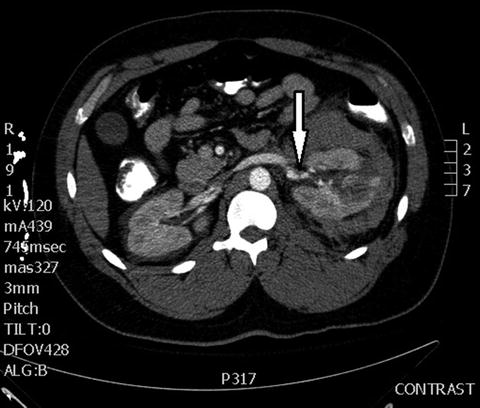

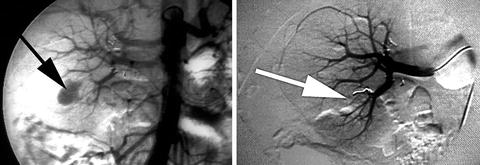

Fig. 15.3

Gunshot wound to left kidney with perinephric hematoma. Arrow indicates urine extravasation. The injury was managed with nephrostomy and stenting.

Technically, surgical exploration is focused on the goals of hemostasis, debridement of devitalized tissue, and repair of the collecting system. Surgical options include repair, partial nephrectomy, and total nephrectomy [14]. Many times, associated injuries will dictate the need for laparotomy.

When a zone II retroperitoneal injury is discovered intraoperatively, the kidney must be explored if there is an expanding hematoma or active bleeding into the peritoneum. Exploration should be considered if there is no preoperative imaging. If the trajectory of penetrating trauma indicates that the ureter is at risk of injury, then this must be explored as well.

The surgical approach to renal injury may include control of the renal pedicle prior to opening Gerota’s fascia or a lateral approach to opening Gerota’s fascia without prior control of the renal pedicle. Control of the renal vessels prior to opening Gerota’s fascia does not result in a higher rate of renal salvage or lower blood loss in the most recent series [15–17]; however, other authors have reported flaws in prior studies leading to ongoing controversy about the role of vascular control prior to renal exploration [18] (Fig. 15.4). Rapid control of the renal hilum en bloc adjacent to the kidney is a solution that avoids prolonged dissection of the renal artery and vein while still allowing vascular occlusion (Fig. 15.5).

Fig. 15.4

Operative photo of right kidney gunshot wound with hilar injury and devascularization of upper pole. Control of the renal hilum will facilitate repair.

Fig. 15.5

(a, b) Control of the renal hilum. Prior to exploration of the injured kidney, rapid control of the hilum may be obtained by encircling the hilar vessels en bloc. Prolonged dissection of the renal vessels is not needed.

The kidney can be exposed after medial mobilization of the right or left colon. A generous vertical incision should be made through Gerota’s fascia, directly over the kidney. The injured kidney should not be bluntly pulled up, as this may decapsulate the kidney or increase the injury. After evacuation of the hematoma, the renal capsule should be identified and dissected free from the surrounding areolar tissue under direct vision. Blunt dissection may be performed away from the site of the injury. After mobilizing the entire kidney, particularly the upper pole, the kidney may be rotated anteriorly. Bleeding should be controlled by compressing the injury, by compressing the renal hilum with a sponge stick, or by placing a vascular clamp across the renal pedicle.

Bleeding from the kidney may be controlled by placing large absorbable mattress sutures through the renal capsule. Topical hemostatic agents may be utilized. A limited debridement of obviously devitalized tissue should be performed; however, debridement should not be overly aggressive. Defects in the collecting system should be closed with absorbable suture (Fig. 15.6). In the event of associated colon or pancreatic injury, viable tissue should be interposed between the injured kidney and colon or pancreas. If there is concern for a urine leak, a drain should be placed adjacent to the injury. If an urgent nephrectomy is required, palpation of a normal size contralateral kidney is adequate assurance of renal function.

Fig. 15.6

Defects in the renal collecting system should be closed separately with absorbable suture. Bleeding may then be controlled using large absorbable mattress sutures, topical hemostatics, or cautery.

Angiography

Angiography is a useful adjunct for management of renal injuries and may be indicated for initial management of hemorrhage, stenting of an intimal injury of the renal artery, or delayed occlusion of a pseudoaneurysm. Angioembolization may improve renal salvage rates compared to surgical exploration (Fig. 15.7). There are no standardized indications for angiography; however, active contrast extravasation on CT scan and perinephric hematoma rim greater than 2.5 cm predict a high likelihood of therapeutic embolization in Grade III and IV renal trauma [19–21]. Importantly, the failure rate for patients who require angioembolization for active hemorrhage is 27 %, frequently requiring laparotomy for treatment [22], although repeat angioembolization is also an option and has been reported to have a 97 % success rate [23]. Angiographic embolization of Grade V renal injuries is not generally recommended due to an excessively high failure rate [24]; however, recent series have demonstrated success in managing select Grade V injuries with an aggressive angiographic approach including repeat embolization after initial failure [23, 25].

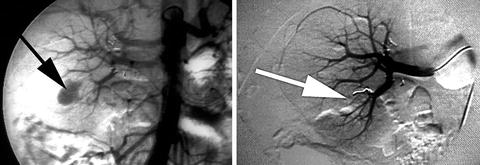

Fig. 15.7

Renal angiogram showing extravasation of contrast from injured lower pole artery and post coil placement.

Management of Ureteral Injuries

The majority of ureteral injuries are caused by penetrating trauma. A high index of suspicion must be maintained based on injuries in proximity to the ureter. Gross hematuria is not a reliable indicator and is absent in about one-third of cases; CT scan may miss up to two-thirds of ureteral injuries [26, 27]. A missed ureteral injury is a cause of significant morbidity and may present as a prolonged ileus, urine leakage from the abdominal wound, oliguria, sepsis, or uremia.

Ureteral injuries are managed by surgical repair. It is important to be aware of the blood supply to the ureter: The upper ureter is supplied by segmental branches from the renal, gonadal, and common iliac arteries entering the ureter from the medial side. After crossing the pelvic brim, the ureter is supplied by branches of the hypogastric artery, entering from the lateral side. The blood supply should be preserved to the greatest extent possible when mobilizing the ureter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree