CHAPTER 2 TRAUMA CENTER ORGANIZATION AND VERIFICATION

The development of trauma care has evolved from a synergistic relationship between the military and civilian medical environments for the past two centuries. During the Civil War, military physicians realized the utility of prompt attention to the wounded, early debridement, and amputation to mitigate the effects of tissue injury and infection, and evacuation of the casualty from the battlefield. World War I saw further advances in the concept of evacuation and the development of echelons of medical care. With World War II, blood transfusion and resuscitative fluids were widely introduced into the combat environment, and surgical practice was improved to care for wounded soldiers. In fact, armed conflict has always promoted advances in trauma care due to the concentrated exposure of military hospitals to large numbers of injured people during a relatively short span of time. Furthermore, this wartime medical experience fostered a fundamental desire to improve outcomes by improving practice. In Vietnam, more highly trained medics at the point of wounding and prompt aeromedical evacuation decreased battlefield mortality rate even further.

TRAUMA SYSTEM AND TRAUMA CENTER ORGANIZATION

Trauma System Organization

The organization of trauma systems and trauma centers derives from efforts to match the supply of trauma services accessible to a population in a specific geographical area with the demand for these services in this area. In this process, resources tend to be concentrated in areas of higher patient volume and acuity. At the core of the system organization is the Level I trauma center. Most of these Level I facilities are located at tertiary referral centers within major urban environments. Along with the patient characteristics, these centers foster the development of trauma system infrastructure elements including trauma leadership, professional resources, information management, performance improvement, research, education, and advocacy. By virtue of their inherently academic disposition, Level I centers generally serve as the regional resource for injury care. In addition, due to their size and resourcing, most are capable of managing large numbers of injured patients and have immediate availability of in-house trauma surgeons.1

The next tier of trauma center organization is the Level II trauma center. Like the Level I center, many of these facilities tend to be located in communities of higher population density. The Level II centers aspire to similar standards as the Level I facilities with the exception that their accreditation is not contingent on having graduate medical education, research capacities, or specific volume requirements. Approximately 84% of U.S. residents have access to Level I or Level II trauma centers within 60 minutes of injury through the aeromedical evacuation system.2 The benefits of this concentration of resources in Level I and II trauma centers are found in the association between trauma center volume and decreased average length of stay and improved patient mortality after injury.3 Recent epidemiological studies of trauma patients show that mortality risk is significantly lower when care is provided in a trauma center rather than in a non-trauma center, which supports continued efforts at regionalization.4 It has also been demonstrated that more severely injured patients, with an injury severity score of >15, have lower mortality rates when treated at Level I trauma centers as compared with lower-echelon centers.5

Trauma Center Organization

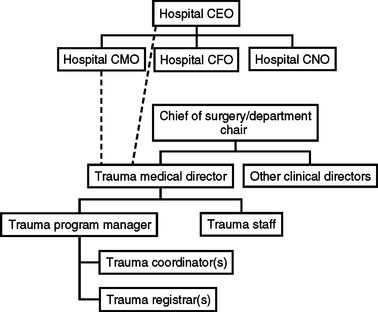

The development and success of a trauma center is contingent upon two basic building blocks: hospital organizational support and medical staff support. First, the hospital and its leadership must have a firm administrative and financial commitment to trauma center development, including incorporating the program into the formal organizational structure at a point commensurate with other clinical care departments of equal organizational stature. Second, medical staff support must be adequate for all levels and types of trauma patient care.6 The basic organizational structure schematic is shown in Figure 1.

Levels of response are guided by patient acuity and level of trauma center resources. Higher patient acuity with more robust resources, as in Level I and II trauma centers, encumbers response from the general/trauma surgeon, emergency physician, anesthesia provider, resident trainees, trauma/emergency nursing, respiratory therapy, radiology technician, security, and religious counsel. The team leader is the surgeon who is ultimately responsible for the patient’s disposition and care, but more importantly, all members of the team work together to streamline patient care according to Advanced Trauma Life Support® guidelines. The trauma service maintains the clinical responsibility for continuity of care in the multidisciplinary environment of injury care. In higher-echelon trauma centers, the trauma service is often a formal clinical service or services under the guidance of trauma staff surgeons. In Level II facilities, these trauma patients are often admitted to the primary surgeon of record and the continuity and oversight to maintain service integrity are provided by the trauma medical director.

The trauma program within a trauma center is a multidisciplinary effort that supports injury care from resuscitation through rehabilitation. Integral staff elements within the trauma program are the trauma medical director, trauma staff, physician specialty staff (orthopedics, neurosurgery, emergency medicine, anesthesia, radiology), trauma program manager/trauma nurse coordinator(s), and trauma registrar(s).6 The key processes that distinguish a trauma center are performance improvement and multidisciplinary peer review.

Trauma Program Manager/Trauma Nurse Coordinator

The position of trauma program manager and trauma nurse coordinator are dual positions or can be coalesced into a single position depending on the size and volume of the trauma program. This position is filled by a highly specialized registered nurse with advanced trauma training who is integral to the development, coordination, implementation, and evaluation of trauma care within the program. This position serves as a key leadership liaison between the staff and process elements within the program (Table 1).

Table 1 Roles of Trauma Program Manager/Trauma Nurse Coordinator

| Role | Definition |

|---|---|

| Clinical | Coordinating continuity and quality of trauma care in multidisciplinary environment |

| Administrative | Helps manage the operational and fiscal activities of the program as well as participates in various committee activities |

| Leadership liaison | Team building |

| Promotes trauma program at local, regional, state, and national levels | |

| Educational | Trains trauma program staff |

| Provides resource plan to train local facilities | |

| Promotes outreach programs | |

| Registry | Oversight of trauma registry data collection and accuracy |

| Performance improvement | Key proponent of trauma program performance improvement process from discovery through loop closure |

| Research | Promotes accurate and reliable data collection and analysis for performance improvement and facilitates clinical research endeavors |

| System advocate | Trauma system development, funding, patient advocate, injury prevention, public education, and outreach |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree