1. Over the past decade, the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Milestone project has recognized the distinction between competence and performance, resulting in an increased expectation of performance measurement and evaluation for independent expert practice.

2. Strategically timed, benchmarked, formative feedback to fellows is needed in order to enable them to acquire the skills, concepts, and confidence necessary for independent consultant practice.

3. Specific Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) in our program are defined for the various clinical experiences and are progressively benchmarked throughout the year, concluding with the ability to achieve independent practice, teach, supervise, and lead a pediatric anesthesia care team.

4. While scholarly activity is integral to the provision of excellence in clinical care, scholarship requires the added expectation of scholarly work that advances knowledge in one’s field of specialization. This activity must be in the public domain and accessible in a format that can be built upon by others.

5. While there is evolving information about the value of simulation in training and even diagnosis of knowledge gaps, no amount of simulation or objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) comes close to contextually based real world practice.

6. A specific goal of the Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) is to not only ensure that a fellow is progressing toward his or her eventual graduation but also to identify a fellow who has not been able to display the judgment, clinical skills, or level of professionalism that is required or expected.

7. Faculty members need to be consultant/experts in pediatric anesthesiology as well as role models. Empirical studies of the characteristics that support these roles are few, but results suggest five specific domains that can be expressed as EPAs.

“Education is time-consuming and costly. The future for improving the safety in pediatric anesthesia may not lie primarily with new equipment and monitoring but in the investment in good-quality initial training followed by fostering an environment that encourages and supports continuing education and training in our specialty.” (1)

“Prior to graduation, each resident must demonstrate that he or she is capable of practicing independently.” (2)

“If you think education is expensive, try ignorance.” (Derek Bok, President of Harvard University, 1971–1990)

I. Background

A. How do you “develop” a pediatric anesthesiologist?

1. Given that subspecialty fellowship training occurs after residency training, faculty members are starting with a board-eligible adult-learner anesthesiologist who has already had some exposure to children during residency.

2. In addition, there is no shortage of organizations willing to provide advisories, guidelines, milestones, and standards for training. That is the easy part.

B. It is more challenging to forecast the future.

1. Changes in public expectation, the ability to access vast numbers of databanks of information about your background, training, experience, and reviews (from 1 to 5 “stars”) is unprecedented.

2. The implementation of the Next Accreditation System (NAS) (3), the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program (4) and the faculty survey are all easily discoverable as well, as is certification status in anesthesiology and pediatric anesthesiology.

3. Another evolving concept during the ACGME Milestone project over the past decade has been the distinction between competence (5) and performance (6) resulting in an increased expectation of performance measurement and evaluation for independent expert practice.

C. It is therefore challenging to contemplate the elements required in the growth and development of a pediatric anesthesiologist in today’s environment and in preparation for the care of children during the next 35 to 40 years of clinical specialty practice. Brown has pointed out in the context of his own vast experience in educating pediatric anesthesiologists that training programs have to include theoretical as well as practical instruction with the goal of producing safe, knowledgeable, and skillful expert clinicians and teachers, a special focus on neonates and infants and knowledge about anesthetic implications of normal and abnormal developmental aspects of childhood (7).

II. Education goals and objectives

A. We expect the designation of “consultant in pediatric anesthesiology” to include the knowledge, judgment, and articulation skills suitable

1. for assuming independent responsibility for the care of pediatric patients.

2. for serving as an expert with the ability to deliberate with others, providing advice and opinions in the general and specialty practice of anesthesiology for children.

3. for functioning as the leader of a pediatric perioperative care team.

4. for meeting with the public, the medical professional, hospitals, and medical schools with regard to the subspecialty practice of pediatric anesthesiology.

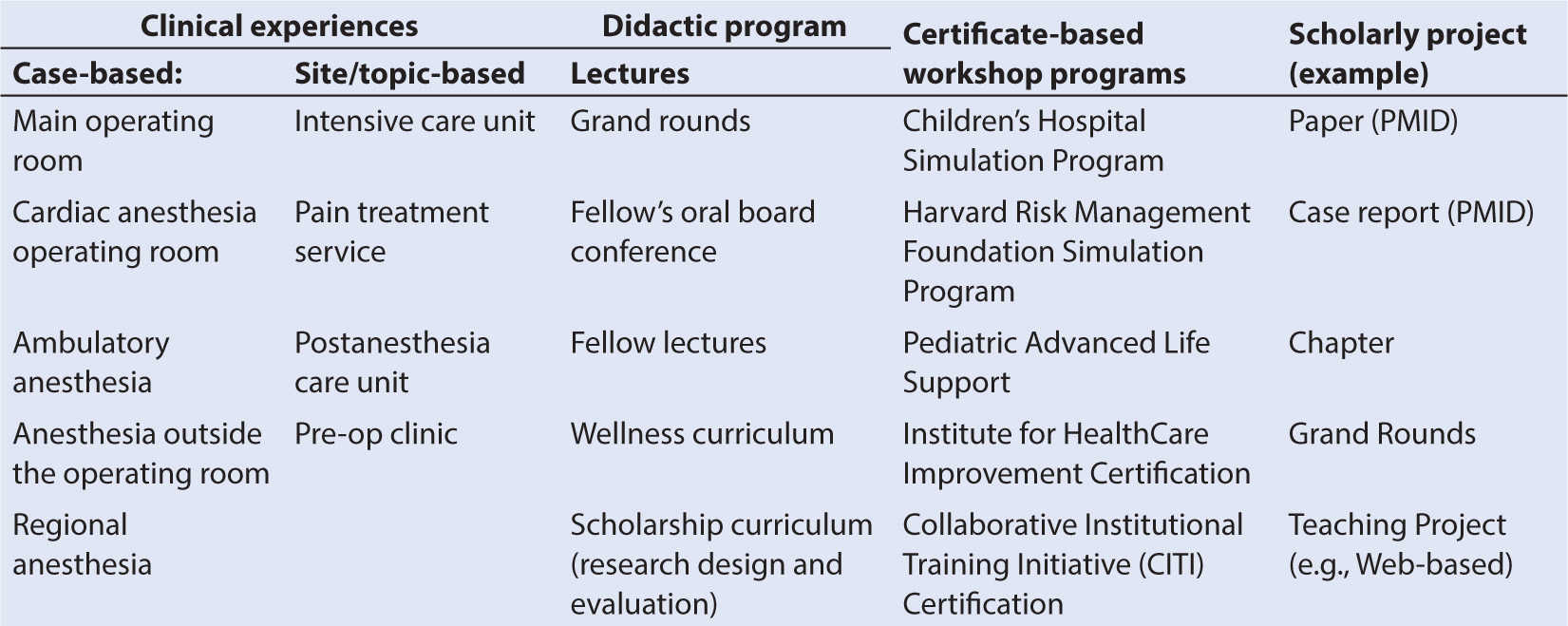

B. Operationalizing these laudable goals involves the creation of a supportive and rigorous learning environment (Table 13.1)—as a first step. Case and procedure numbers are typically the criteria threshold to meet, and minimum requirements in pediatric anesthesiology have recently been introduced (Table 13.2).

C. The second step is the provision of strategically timed, benchmarked, formative feedback to fellows in order to enable them to acquire the skills, concepts, and confidence necessary for independent consultant practice. Moreover, it is clear that time-based or benchmarked performance can be assessed in anesthesiology training (8,9) and that additional benefits, such as reciprocal enhancement of effective clinical teaching, are likely to occur.

TABLE 13.2 Review committee for anesthesiology

Category | Minimum number effective July 1, 2014 |

Pediatric anesthesiology fellowship minimums case numbers | |

Total number of patients | 240 |

■ Age of patients | |

Neonates | 15 |

1–11 mo | 40 |

1–2 y | 40 |

3–11 y | 75 |

12–17 y | 30 |

■ American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) level | |

ASA 1 | 25 |

ASA 2 | 42 |

ASA 3 | 50 |

ASA 4 | 20 |

ASA 5 | 0 |

ASA 6 | 0 |

■ Procedures | |

Epidural/caudal | 10 |

General | 200 |

Intrathecal | 0 |

Peripheral nerve block | 5 |

Arterial cannulation | 30 |

Central venous cannulation (CVC) | 12 |

Fiberoptic intubation | 4 |

■ Type of surgery | |

Airway (except tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy) | 7 |

Cardiac—with bypass | 15 |

Cardiac—without bypass | 5 |

Craniofacial—without cleft | 3 |

Intra-abdominal/intracavitary | 12 |

Intracranial neurosurgery | 9 |

Intrathoracic noncardiac | 5 |

Major orthopedic | 5 |

Total neonate emergency | 3 |

Total solid organ transplant | 0 |

Other operative | 55 |

Other nonoperative | 10 |

■ Pain management | |

Central neuraxis blocks | 0 |

Consultations and PCA | 17 |

Peripheral nerve blocks | 6 |

D. Performance metrics in medical specialties are readily identifiable by experts, framed within the crucible of EPAs. This evolving concept is now incorporated into ACGME phase I training programs (10–12).

1. Specific EPAs in our program are defined for the various clinical experiences listed in Table 13.1, and are benchmarked for the year, including the ability to achieve independent practice, teach, supervise, and lead a pediatric anesthesia care team.

2. The EPA evaluations are sourced from faculty (daily), advisors (quarterly, as summative evaluations), the CCC (quarterly, as summative evaluations), self-evaluations (monthly), 360-degree evaluations (operating room [OR] nurse, attending surgeon, surgical fellow, affiliating anesthesiology resident—all quarterly).

E. The third step consists of didactic sessions (daily lectures), pediatric anesthesiology-specific simulations, journal clubs, mock-oral exams, pediatric advanced life support, Institute for HealthCare Improvement (IHI) Certification, and Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) Certification.

F. Finally, while scholarly activity is integral to the provision of excellence in clinical care, scholarship requires the added expectation of scholarly work that advances knowledge in one’s field of specialization.

1. This activity must be in the public domain and accessible in a format that can be built upon by others, such as abstracts/posters/presentations made at professional meetings, articles published, (as identified by their PubMed identification numbers [PMID]), textbooks, chapters, and reviews, lectures greater than 30 minutes duration (e.g., grand rounds, case presentations) at local, regional, national, or international conferences, documented work on a grant or research project, and education-related service on national committees.

The completion of all of these activities will result in a “digital diploma” at the end of our fellowship, a diary of clinical training and education activity that reflects the training experience in pediatric anesthesiology.

III. A developmental approach for the adult learner

A. The “development” of a pediatric anesthesiologist is a process, not an endpoint.

1. While the training program is finite in time, learning and development do not end with the graduation ceremony.

2. While we do not know the changes needed, we do know that changes will be needed.

3. Therefore, trainees must not only be guided through the technical and humanistic aspects of pediatric anesthesia, but also toward continuous growth as a person and a learner (13).

CLINICAL PEARL As part of continuous growth and the development of expertise, shifting the focus from the study of problem solving to problem definition is crucial, the distinction being that the solution cannot necessarily be determined or foreseen from the structure of the task (14).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree