CHAPTER 15 Traction Therapy

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

The most common types of traction therapy are based on the duration of its application, which may be intermittent (alternating traction and relaxation with cycles of up to a few minutes), sustained (20 to 60 minutes) or continuous (hours to days).1–5 Traction therapy can also be described according to the direction of its primary force, whether axial or distraction. Axial traction attempts to limit the force applied to the superoinferior (e.g., caudad-cephalad) axis of the spine, while distraction allows the provider or patient to orient the direction and amount of force along the three cardinal axes by varying the position of the body. Axial traction using at least 30% to 50% of body weight is considered high-dose axial traction (Table 15-1).

TABLE 15-1 Categories of Traction Therapies Based on Temporal (Sustained vs Intermittent) and Force (Focused vs Dispersed) Variables

| Sustained | Intermittent | |

|---|---|---|

| Focused | Positional distraction Autotraction Positional distraction | Distraction-manipulation Flexion-distraction (Cox) Leander technique |

| Dispersed | Sustained traction Split-table traction Gravity traction LTX 3000 | Intermittent traction VAX-D DRX-9000 Split-table traction |

Distraction is further subdivided into distraction manipulation and positional distraction. Perhaps the best known type of distraction manipulation is flexion-distraction, which is sometimes referred to as Cox technique after one of its main promoters, chiropractor James Cox. In distraction manipulation, the provider attempts to apply distraction force along specific planes (e.g., flexion, extension, lateral flexion, or rotation) to position the targeted spinal segments to receive spinal mobilization or manipulation based on patient symptoms and manual examination findings.6 Other forms of distraction manipulation traction include the Leander technique and the Saunders ActiveTrac method. The most common example of positional distraction is autotraction, a technique in which the patient controls the direction and force of traction based on the amount of relief experienced.

History and Frequency of Use

Various forms of traction therapy have been used to treat spinal disorders for almost 4000 years, since at least 1800 bc.7 Hippocrates (fourth to fifth century bc), was likely the first practitioner to create an apparatus to apply spinal traction.8 By the nineteenth century, the traction bed was used to treat LBP, scoliosis, rickets, and other spinal deformities; other forms of traction therapy using corsets, chairs, and suspension were also promoted at that time by various practitioners.9 Traction became a common treatment for CLBP in the early twentieth century, when firmer opinions and theories were formulated regarding how it should be applied, including the ideal amount of force, degree of pull, duration of pull, and timing of force intervals.1 The British physician Cyriax promoted traction therapy for not only CLBP but also for lumbar disc lesions, theorizing that it could produce negative pressure in the disc, thereby reducing disc herniations.2 Other practitioners suggested that off-axis movements, such as flexion or extension, also be added to axial traction to preferentially reduce back or leg pain, and created the techniques of autotraction and flexion-distraction, as mentioned above.3,4

A prospective study of health care utilization among 1342 patients with low back pain (LBP) who presented to general practitioners in Germany reported that 10% used traction in the subsequent 1 year follow-up.10 Traction was the sixth most commonly reported modality after local heat (34%), massage (31%), spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) (26%), electrotherapy (17%), and acupuncture (13%). The use of traction was statistically significantly higher among those with CLBP, with an odds ratio of 2.0 (95% CI 1.1 to 3.6).

Procedure

Traction can be applied in a variety of ways according to the specific device used. With axial traction, patients are most often treated while lying supine on a traction table with their knees and hips partly flexed or over a cushion (Figure 15-1). Typically a harness is applied to both the pelvis and the chest and force is transmitted from the device through the harnesses. Most traction tables are split in the middle; the upper portion remains stationary while the lower portion is mobile, mounted on a track or bearings. The lower portion is slowly pulled away from the upper portion during treatment. This design reduces the force needed to counteract body weight and separate the vertebrae. Although originally applied by manual means or by using weights, axial traction is most often applied with motorized or hydraulic systems today. Modern traction tables can be programmed to gradually increase the amount of force, or cycle through patterns of traction and relaxation as needed.

Figure 15-1 Supine lumbar spine traction therapy.

(From Olson KA. Manual physical therapy of the spine. St. Louis, 2008, Saunders.)

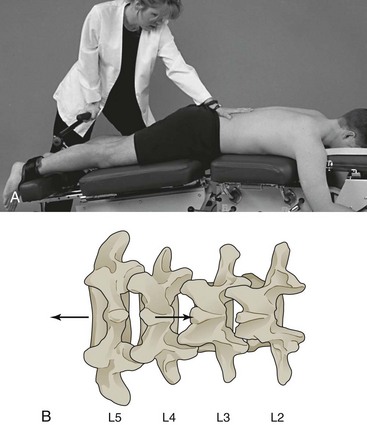

Patients receiving positional distraction or distraction manipulation are often placed in a prone or side-lying position on a distraction table (Figure 15-2). The lower part of the table can move in several planes, independently of the upper part. The provider can lower or elevate the lower or caudal portions of the table to create distraction (axial traction combined with off-axis motion) in the plane desired. A harness may be used to secure the pelvis or ankles and transmit the distraction forces along the body. Some techniques, for example flexion-distraction, require the provider to use one hand to apply pressure to the spine and the other to operate the table (Figure 15-3). This allows forces to be concentrated in a smaller area as opposed to being dispersed throughout the spine. While some distraction tables are operated manually, others are motorized and can be programmed with varying degrees of movement amplitude, force, and time cycles.

Figure 15-2 Prone lumbar spine traction therapy.

(From Olson KA. Manual physical therapy of the spine. St. Louis, 2008, Saunders.)

Theory

Mechanism of Action

Several theories have been proposed to explain the possible clinical benefit of traction therapy for CLBP. Axial distraction of the lumbar motion segment is thought to change the position of the nucleus pulposus relative to the posterior annulus fibrosus or change the disc-nerve interface, which could decrease mechanical pressure exerted on the nerve by a displaced disc.4,5,11,12 These effects are plausible based on studies examining the kinematics of the lumbar spine during traction. In addition to separating the vertebrae, traction has been shown to reduce pressure within the nucleus pulposus and increase the size of the lateral foramen.13,14 However, it is unlikely that such mechanical changes observed in a prone position would be sustained after a patient resumes an upright, weight-bearing posture. Any lasting clinical response to traction therapy would therefore more likely be related to its biologic effects on the motion segment or neural tissues. Complicating the issue further is that not all traction therapies exert the same force on the spine and animal studies have found the mechanobiology of the disc to be sensitive to the amount, frequency, and duration of loading and unloading.15

It is possible that some forms of traction stimulate disc or joint repair, whereas others promote tissue degradation.16,17 Although these variables have not been systematically examined, even in animal models, what is known regarding disc mechanobiology should alert us to the possibility that not all forms of traction therapy are equal. If distracting the spine can influence disc and joint mechanobiology, different modes of traction may result in different clinical results. Systematic reviews (SRs) of lumbar traction therapy have typically not considered that different effects may exist based on force and time parameters. Clinical studies of traction therapy have most often included patients with a mix of clinical presentations including back-dominant LBP, leg-dominant LBP, or both. However, a patient with predominantly axial LBP and no radiculopathy is likely experiencing pain from a sclerotomal source, such as facet joints or disc, whereas radicular pain, even if caused by disc herniation, may be predominately of neural origin. Although it is reasonable to suspect that traction therapies may affect these conditions differently, there is insufficient evidence to support this hypothesis.

Distraction manipulation and positional distraction are mechanically different than intermittent or sustained axial traction. Rather than allowing forces to be dispersed throughout the lumbar tissues, they attempt to concentrate the forces in a smaller area. Autotraction, for example, allows the patient to concentrate the force by finding the position that most relieves their pain and applying distraction in that position. Distraction manipulation, most often used by chiropractors and physical therapists, is performed on treatment tables that allow the operator to determine the moment-to-moment vector and timing of the distractive force. If manual force is applied to the area of spinal dysfunction while it is in traction, the additional effects of SMT or mobilization (MOB) may also be at play; those interventions are reviewed in Chapter 17.

Assessment

Before receiving traction therapy, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required. The clinician should also inquire about general health to identify potential contraindications to traction. Radiographs of the lumbar spine may be taken to exclude disease states such as severe osteoporosis or ligamentous instability that might compromise bone or soft-tissue integrity. If signs or symptoms of neurologic compromise are present, appropriate imaging (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography) should be obtained to determine the cause.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found high-quality evidence against the use of traction for CLBP.18

The CPG from Europe in 2004 found no evidence that traction therapy was more effective than other conservative management options or sham traction therapy for CLBP.19 That CPG did not recommend the use of traction therapy for CLBP.

The CPG from Italy in 2007 did not recommend the use of traction therapy for CLBP.20

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 did not recommend the use of traction therapy for CLBP.21

The CPG from the United States in 2007 found fair evidence of no benefit for traction therapy in the management of CLBP.22

Findings from the above CPGs are summarized in Table 15-2.

TABLE 15-2 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations on Traction Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 18 | Belgium | Not recommended |

| 19 | Europe | Not recommended |

| 20 | Italy | Not recommended |

| 21 | United Kingdom | Not recommended |

| 22 | United States | Fair evidence against use |

Systematic Reviews

Cochrane Collaboration

An SR was conducted in 2006 and updated in 2010 by the Cochrane Collaboration on traction therapy for acute, subacute, and chronic LBP.23 A total of 25 RCTs were identified: one examined subacute LBP and eight examined chronic LBP.3,24–29 The remaining RCTs either included patients with a mixed duration of LBP or did not report the duration of LBP.3,28,30–44 For LBP with or without neurologic involvement, statistically significant differences were not found for (1) traction versus control on any outcome, (2) traction versus interferential treatment for pain and function, (3) static versus intermittent traction, and (4) traction added to physical therapy versus physical therapy alone for pain and function.25,31,32,34 However, one RCT observed statistically significant global improvement for autotraction versus mechanical traction.27 For LBP with neurologic involvement, statistically significant differences were not observed for continuous versus intermittent traction.28,30,35,39,41,42,44

Furthermore, RCTs of autotraction were inconsistent for LBP with neurologic involvement. One RCT observed short-term improvements in pain after a few weeks but this was not sustained after 3 months of follow-up for traction plus corset versus corset alone.37 Another RCT found statistically significant improvement for autotraction versus sham traction combined with bed rest and analgesics, yet autotraction was not significantly different from sham traction in another RCT.38,43

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree