CHAPTER 134

Torticollis

(Wryneck)

Presentation

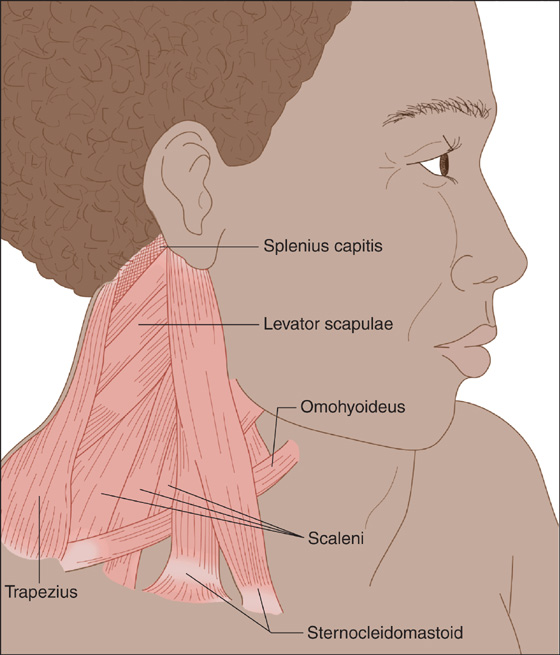

The patient, usually a young or middle-aged adult, complains of neck pain and is unable to turn his head, usually holding it twisted to one side, with involuntary spasm of the neck muscles and the chin pointing to the other side. These symptoms may have developed gradually, after minor turning of the head, after vigorous exercise, or overnight during sleep. Spasm in the occipitalis, sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, splenius cervicis, or levator scapulae may be visible and/or palpable (Figure 134-1).

Figure 134-1 Wryneck.

What To Do:

Ask the patient about precipitating factors, and perform a thorough physical examination, looking for muscle spasm, point tenderness, signs of injury, nerve root compression, masses, or infection. Include a careful nasopharyngeal examination as well as a basic neurologic examination.

Ask the patient about precipitating factors, and perform a thorough physical examination, looking for muscle spasm, point tenderness, signs of injury, nerve root compression, masses, or infection. Include a careful nasopharyngeal examination as well as a basic neurologic examination.

When forceful trauma is involved and fracture, dislocation, or subluxation is possible, obtain lateral, anteroposterior, and odontoid radiographic views of the cervical spine. If there are neurologic deficits, a CT scan or MRI may be better to visualize nerve involvement (as well as herniated disk, hematoma, or epidural abscess).

When forceful trauma is involved and fracture, dislocation, or subluxation is possible, obtain lateral, anteroposterior, and odontoid radiographic views of the cervical spine. If there are neurologic deficits, a CT scan or MRI may be better to visualize nerve involvement (as well as herniated disk, hematoma, or epidural abscess).

With signs and symptoms of infection (e.g., fever, toxic appearance, lymphadenopathy, tonsillar swelling, trismus, pharyngitis, or dysphagia), especially in the pediatric patient, obtain a contrast-enhanced CT scan and consider obtaining a complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to help rule out retropharyngeal abscess formation. Arrange for specialty consultation as needed.

With signs and symptoms of infection (e.g., fever, toxic appearance, lymphadenopathy, tonsillar swelling, trismus, pharyngitis, or dysphagia), especially in the pediatric patient, obtain a contrast-enhanced CT scan and consider obtaining a complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to help rule out retropharyngeal abscess formation. Arrange for specialty consultation as needed.

When there is no suspicion of a serious illness or injury, carefully examine the side of the neck in spasm for tender trigger points. Press your examining finger firmly and deeply into the neck muscles along muscular borders and their origins and insertions, searching for one or two spots approximately the size of your fingertip that cause the patient to wince in pain. If a localized trigger point is discovered, you may consider treating this as for any other source of myofascial pain and thus inject these areas with 5 to 10 mL of bupivacaine (Marcaine) 0.25% to 0.5%, with or without a corticosteroid (see Chapter 123). Trigger-point injection can often partially or completely relieve the symptoms of the acute and painful form of torticollis.

When there is no suspicion of a serious illness or injury, carefully examine the side of the neck in spasm for tender trigger points. Press your examining finger firmly and deeply into the neck muscles along muscular borders and their origins and insertions, searching for one or two spots approximately the size of your fingertip that cause the patient to wince in pain. If a localized trigger point is discovered, you may consider treating this as for any other source of myofascial pain and thus inject these areas with 5 to 10 mL of bupivacaine (Marcaine) 0.25% to 0.5%, with or without a corticosteroid (see Chapter 123). Trigger-point injection can often partially or completely relieve the symptoms of the acute and painful form of torticollis.

After trigger-point injection or when a trigger point cannot be found (or the patient elects not to have the injection), have the patient apply ice to decrease inflammation and spasm for the first 48 hours; then switch to heat. If not contraindicated, give acetaminophen or anti-inflammatory analgesics (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) and a muscle relaxant—consider metaxalone (Skelaxin), cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), or diazepam (Valium).

After trigger-point injection or when a trigger point cannot be found (or the patient elects not to have the injection), have the patient apply ice to decrease inflammation and spasm for the first 48 hours; then switch to heat. If not contraindicated, give acetaminophen or anti-inflammatory analgesics (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) and a muscle relaxant—consider metaxalone (Skelaxin), cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), or diazepam (Valium).

Alternating heat with ice massages may also be helpful, as well as gentle range-of-motion exercises and friction massage.

Alternating heat with ice massages may also be helpful, as well as gentle range-of-motion exercises and friction massage.

A soft cervical collar can be provided if it affords comfort. This should be worn for as short a period as tolerated. Position the wider segment of the collar on the side that produces the greatest comfort for the patient.

A soft cervical collar can be provided if it affords comfort. This should be worn for as short a period as tolerated. Position the wider segment of the collar on the side that produces the greatest comfort for the patient.

Inform the patient that with successful trigger-point injection, there may be mild soreness the next day and complete resolution of discomfort over the next week. Symptoms usually resolve spontaneously within 2 weeks without treatment. If symptoms persist beyond this period, further evaluation is warranted.

Inform the patient that with successful trigger-point injection, there may be mild soreness the next day and complete resolution of discomfort over the next week. Symptoms usually resolve spontaneously within 2 weeks without treatment. If symptoms persist beyond this period, further evaluation is warranted.

What Not To Do:

Do not overlook infectious causes presenting as torticollis, especially the pharyngotonsillitis of young children, which can soften the atlantoaxial ligaments and allow subluxation.

Do not overlook infectious causes presenting as torticollis, especially the pharyngotonsillitis of young children, which can soften the atlantoaxial ligaments and allow subluxation.

Do not fail to consider the unusual disk herniation or bony subluxation that, on occasion, can present as acute wryneck or torticollis.

Do not fail to consider the unusual disk herniation or bony subluxation that, on occasion, can present as acute wryneck or torticollis.

Do not undertake violent spinal manipulations in the emergency department, which can make acute torticollis worse and potentially cause other problems.

Do not undertake violent spinal manipulations in the emergency department, which can make acute torticollis worse and potentially cause other problems.

Do not confuse torticollis with a dystonic drug reaction (see Chapter 1) from phenothiazines or butyrophenones.

Do not confuse torticollis with a dystonic drug reaction (see Chapter 1) from phenothiazines or butyrophenones.

Discussion

Torticollis is an involuntary twisting of the neck to one side, secondary to spasm and contraction of the neck muscles. The ear is pulled toward the contracted muscle while the chin is facing in the opposite direction. The term torticollis is derived from the Latin words tortus (“twisted”) and collum (“collar” or “neck”). Twisting of the neck may also be accompanied by the elevation of one shoulder up toward the contracted neck muscles.

Although torticollis may signal an underlying disorder, in the acute care setting, it is usually a local musculoskeletal problem—only more frightening and noticeable because of the apparent deformity of the neck—and need not always be worked up comprehensively when it first presents to the clinician.

Torticollis can be a symptom as well as a disease, with a host of underlying disorders. Abnormalities of the cervical spine can range from fracture, subluxation, and osteomyelitis to tumor. Infectious causes include retropharyngeal abscess, cervical adenitis, tonsillitis, and mastoiditis. Head tilting can occur to compensate for an essential head tremor, and idiopathic spasmodic torticollis and cervical dystonia should be suspected when symptoms are prolonged.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree