Chapter 8 Therapeutic massage treatment for headache and neck pain

INTRODUCTION

The information up to this point has involved both theory and methodology specifically focused on understanding, assessing, determining the appropriateness of treatment of and finally developing massage treatment approaches for headache and neck pain.

MASSAGE TREATMENT

A variety of massage applications can be employed to accompany the methods outlined in this chapter.

A combination of physical effects occurs, apart from the undoubted anxiety-reducing (Sandler 1983) influences that involve biochemical changes. Massage techniques vary greatly. The following are a few examples:

• Plasma cortisol and catecholamine concentrations alter markedly as anxiety levels drop and depression is also reduced (Field 1992).

• Serotonin levels rise as sleep is enhanced, even in severely ill patients – preterm infants, cancer patients, and people with irritable bowel problems as well as HIV-positive individuals (Acolet 1993, Ferel-Torey 1993, Xujian 1990).

• Pressure strokes tend to move fluid content, encouraging venous, lymphatic, and tissue drainage.

• Increase of blood flow results in fresh oxygenated blood, which aids in normalization via increased capillary filtration and venous capillary pressure.

• Edema is reduced and so are the effects of pain-inducing substances which may be present.

• Decreases occur in the sensitivity of the gamma efferent control of the muscle spindles, thereby reducing any shortening tendency of the muscles (Puustjarvi 1990).

• A transition occurs in the ground substance of fascia (the colloidal matrix) from gel to sol, which increases internal hydration and assists in the removal of toxins from the tissue (Oschman 1997).

• Pressure techniques can have a direct effect on the Golgi tendon organs, which detect the load applied to the tendon or muscle.

Outcome-based massage

• lengthen shortened neck extensors

• address trigger point referred pain from the sternocleidomastoid muscle

People enjoy massage because it feels good, and is a nurturing, integrated experience. This major strength of massage needs to be preserved, not replaced. General nonspecific full body massage – based on the outcomes of decreased sympathetic arousal and maladaptive stress response, tactile pleasure sensation and nurturing – is effective in the treatment of headache and neck pain symptoms even if nothing else is done (Yates 2004). It is prudent to preserve these qualities and benefits of massage when addressing specific conditions such as headache and neck dysfunction.

The massage therapist can increase the effectiveness of massage treatment by becoming more skilled in how to target a specific outcome, such as reducing pain and stiffness in the cervical area. This is accomplished by incorporating assessment skills and targeted treatment methods based on that assessment information into the full body massage session. Targeted treatment such as for deactivation of trigger points can feel intense and/or uncomfortable. These methods are often better accepted and integrated by the patient when ‘wrapped’ in the pleasure and nurturing experience of a general massage session. Since headache and neck pain are so common and massage has been shown to be beneficial (see Chapter 5), the massage therapist needs to be skilled in this area.

Based on many years of professional experience, client populations that typically often seek massage experience headache and neck pain. Causal factors are typically a cumulative response to many different adaptive responses, such as postural distortion, a combination of short soft tissue and long weak muscles or lax ligaments, various types of joint dysfunction (especially instability), generalized stress and breathing dysfunction, repetitive strain, lack of movement – and the list goes on – as discussed in detail elsewhere in this book.

It is logical that individuals undergoing medical procedures such as surgery may develop pain secondary to the positioning required to perform the procedure, extended bed rest, reduced physical activity, anxiety and other predisposing factors. Headache and neck pain is a major treatment concern in health care in many populations, including children and adolescents, in postural distortion during pregnancy, postural strain from obesity, and muscle pain as part of osteoporosis and other conditions related to aging (Yates 2004).

Management of headache and neck pain and improvement in function require lifestyle changes on the part of the client/patient and compliance with various treatment protocols. Chapter 9 also discusses lifestyle choices which could possibly be creating the symptom and be the cause of the dysfunction. Unfortunately, many people are not diligent when it comes to implementing these changes. For these individuals, headache and neck pain can frequently be symptomatically managed with massage. This means that the massage outcome goal is pain management more so than targeting a change in the factors causing the condition. And just as pain medication will wear off, so will the effects of massage, so it may need to be more frequent in order to maintain symptom management. At the end of Chapter 6, massage treatment protocols are provided for various breathing dysfunctions, which can be a cause of head and neck pain.

The goal is not to ‘fix’ the pain but to both mask it and superimpose short-term beneficial changes in the tissue. If these patients are treated with medication they would take muscle relaxants, some sort of analgesic and anti-inflammatory, and possibly mood-modulating drugs. All of these medications have potentially serious side effects, with long-term use making them undesirable in management of chronic head and neck pain. Massage may accomplish similar results to that achieved by medication, if applied frequently and consistently – and without the side effect problem. Massage can replace or help reduce the dose of various medications, and it can be used indefinitely to treat the symptoms of chronic headaches and neck dysfunction. Massage has few (if any) side effects, is cost effective, produces at least short-term benefits and since people typically enjoy massage they tend to be compliant about attending sessions (Fritz 2004). This situation is not ideal but it is not the worst-case situation either, and it is possible that eventually the patient/client will reach a point in their life when they are able and willing to be more responsible for the lifestyle and attitude changes necessary to manage head and neck pain.

Qualities of touch

Massage application involves touching the body to manipulate the soft tissue, influence body fluid movement, and stimulate neuroendocrine responses. How the physical contact is applied is considered the qualities of touch. Based on information from massage pioneer Gertrude Beard and current trends in therapeutic massage, the massage application can be described as follows (De Domenico 2007).

Rhythm

The on/off aspect of compression applied to a trigger point to encourage circulation to the area should be rhythmic, as should lymphatic drainage application.

Components of massage methods

All massage methods introduce forces into the soft tissues. These forces stimulate various physiologic responses.

Some massage applications are more mechanical than others – connective tissue and fluid dynamics are most affected by mechanical force. Connective tissue is influenced by mechanical forces by changing its pliability, orientation, and length (Yahia et al 1993).

The movement of fluids in the body is a mechanical process (e.g., the mechanical pumping of the heart). Forces applied to the body mimic various pumping mechanisms of the heart, arteries, veins, lymphatics, muscles, respiratory system, and digestive tract (Lederman 1997).

Neuroendocrine stimulation occurs when forces are applied during massage that generate various shifts in physiology (NCCAM 2004):

• Massage causes the release of vasodilator substances that then increase circulation in an area.

• Massage stimulates the relaxation response, reducing sympathetic autonomic nervous system dominance (Freeman & Lawlis 2001).

• Forces applied during massage stimulate proprioceptors which alter motor tone in muscles (Lederman 1997).

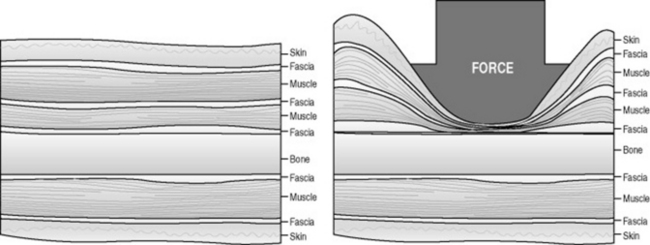

Compression loading (Figure 8.5)

Compressive forces occur when two structures are pressed together. Compression moves down into the tissues, with varying depths of pressure adding bending and compressive forces. Compressive force is a component of massage application that is described as depth of pressure.

Compression loading is a main method of trigger point treatment.

Bending loading (Figure 8.6)

Areas of ‘stuck’ skin often suggest underlying problems (see Chapter 6).

Shear loading (Figure 8.7)

The massage method called friction uses shear force to generate physiologic change by increasing connective tissue pliability and to insure that tissue layers slide over one another instead of adhering to underlying layers, creating bind. Application of friction also provides pain reduction through the mechanisms of counterirritation and hyperstimulation analgesia (Yates 2004). Friction prevents and breaks up local adhesions in connective tissue, especially over tendons, ligaments, and scars (Gehlsen et al 1999).

• This method should not be used during an acute illness, or soon after an injury, or close to a fresh scar, and should only be used if adaptive capacity of the client can respond to superimposed tissue trauma.

• Excess friction (shearing force) may result in an inflammatory irritation that causes many soft tissue problems.

• Friction will increase blood flow to an area but also cause edema from the resulting inflammation and tissue damage from the frictioning procedure.

Rotation or torsion loading (Figure 8.8)

Changes in depth of pressure and drag determine whether the kneading manipulation is perceived by the client as superficial or deep. By the nature of the manipulation, the pressure and pull peak when the tissue is lifted to its maximum, and decrease at the beginning and end of the manipulation.

Joint movement methods

Types of joint movement methods

• active assisted movement, which occurs when both the client and the massage practitioner move the area

• active resistive movement, which occurs when the client actively moves the joint against a resistance provided by the massage practitioner.

Shortened tissue located in deep layers of muscle, or in a muscle that is difficult to lengthen by moving the body, can be addressed with local bending, shearing, and torsion in order to lengthen and stretch the local area, and this is easy to accomplish during the course of the massage (Box 8.1).

Box 8.1 Sequence of massage based on clinical reasoning to achieve specific outcomes

1. Massage application intent (outcome) determines mode of application and variation in quality of touch:

2. Mode of application with variations in quality of touch generates mechanical forces.

3. Mechanical forces (tension, compression, bend, shear, torsion to effect tissue changes from physical loading) leading to influence on physiology.

5. These factors contribute to development of treatment approach.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree