Chapter 2 The system of assessment and care of the primary survey positive patient

Introduction

Emergency situations cause stress, especially if they are unfamiliar or present new and different challenges. Specific life threatening medical emergencies may only be experienced by most practitioners a few times in their career1,2 and even experienced clinicians require training and practice to maintain confidence and skills. Using a system of care and assessment will improve consistency. This chapter aims to set out a system of assessment for the patient with emergency care needs. It can only offer a framework; proper application will require training, flexibility, common sense, and experience (Box 2.1).

Recognition of immediately life threatening problems

Most patients do not have an immediately life-threatening airway, breathing, circulation, or neurological problem. The patient who is talking normally, is fully orientated, is not pale or sweaty, has no dyspnoea, has a normal pulse, and is not breathless is unlikely to be in immediate danger. However the patient’s condition may change very quickly and some need careful monitoring and re-evaluation (for example, the patient with chest pain may have a sudden cardiac arrest). Making decisions about the presence or absence of an immediate threat to life can be difficult. There is evidence that important clinical signs of urgent airway, breathing, circulation, or neurological problems may be easily missed, misinterpreted, or mismanaged in the emergency setting in hospital practice;1,2 the risk of clinical errors in pre-hospital practice is likely to be greater.

Fortunately, there are common presentations for most acute medical emergencies that can be anticipated. These include shortness of breath, chest pain, abdominal pain, collapse, coma, and seizures (Box 2.2).

The primary survey positive patient

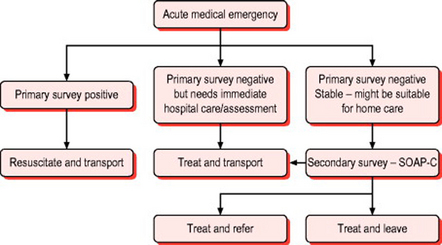

A number of excellent reference texts and resources exist describing the priorities and immediate actions for assessing acutely unwell patients in the hospital and general practice setting.3–10 The approach and techniques advocated are equally applicable in the resource limited community care environment and during transport to hospital. Similarly, the ABCDE approach taught on standard life support courses is as applicable to acute medical emergencies as it is to resuscitation from cardiac arrest and the management of major trauma. This structured approach is illustrated in Figure 2.1. This reflects the central doctrine of emergency care that immediate assessment and management of a life threatening condition does not require a precise diagnosis. It also illustrates the importance of considering early transport to definitive care with emergency treatment compared with resuscitation en route.

After ensuring the scene is safe, the practitioner should aim to undertake a rapid primary survey (Box 2.3). In many patients, the primary survey may be completed very quickly. The common pathways to cardiac arrest in acute medical emergencies are airway obstruction, respiratory failure, circulatory failure, and neurological failure. The aim of the primary survey is to seek out evidence of these in order to target specific resuscitative interventions.

Box 2.3 Rapid primary survey

Circulation Assessment

There is unlikely to be an immediately life threatening circulation problem if:

Detailed assessment of the circulation should identify the presence of shock and a systemic inflammatory response to infection. Shock is a failure of tissue oxygenation. The classic signs include prolonged capillary refill, tachycardia, tachypnoea, and sympathetic nervous system stimulation (pallor, sweating and peripheral vasoconstriction). ‘Sepsis’ refers to evidence of systemic infection (for example, pneumonia, meningococcal disease) accompanied by systemic inflammatory responses. These include a pulse rate greater than 90, a respiratory rate greater than 20, and a temperature above 38° C or below 36° C. Acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage may be missed if the clinical signs of bleeding are not assessed. Finally, assessment of the circulation in medical emergencies includes an assessment of heart rhythm and a search for evidence of heart failure and myocardial dysfunction (tachycardia, 3rd or 4th heart sounds, systolic murmur).

Patients with a serious illness requiring immediate transport to hospital

There are a number of common problems where the primary survey may confirm that the patient is ‘stable’ but they may still have a condition that needs immediate treatment, usually in hospital. Chest pain, vascular occlusions, severe shortness of breath, severe abdominal pain, and acute neurological deficit are examples. In such cases the focus of treatment is rapid transport to hospital with any necessary interventions being provided during the journey.

The secondary survey

The SOAPC system

The system that we have adopted (Box 2.4) is based heavily on problem oriented methodology:11

Objective information: examination findings, augmented when appropriate, by investigations and information from the patient record (for example, electronic record or patient held records)

Objective information: examination findings, augmented when appropriate, by investigations and information from the patient record (for example, electronic record or patient held records) Analysis: your opinion as to the probable cause of the problem and whether other serious problems need to be ruled out

Analysis: your opinion as to the probable cause of the problem and whether other serious problems need to be ruled out Plan: the further care of the patient including advice, treatment with drugs, whether the patient requires another healthcare facility or can stay at home with appropriate follow up and ‘safety net’ advice

Plan: the further care of the patient including advice, treatment with drugs, whether the patient requires another healthcare facility or can stay at home with appropriate follow up and ‘safety net’ advice