Key Clinical Questions

What terms and concepts are required for understanding suicidality?

What are chronic or predisposing risk factors for suicide?

What are acute or potentiating risk factors for suicide?

What are protective risk factors for suicide?

How does the hospitalist determine in the patient is at baseline risk for suicide or elevated risk?

How does the hospitalist device a plan of care for the suicidal patient?

Introduction

Suicidality (defined as one’s attraction to suicide) is very common in patients with severe psychiatric disorders even though completed suicide (killing oneself) is relatively rare. The risk of suicidality is never zero. Even patients hospitalized for medical or surgical reasons, many of whom also have severe psychiatric disorders, experience suicidality but since the focus of their care is medical or surgical rather than psychiatric, their suicidality often goes unnoticed, unevaluated and untreated. Given, then, the hospitalist’s high likelihood of treating patients experiencing suicidality, all hospitalists require the knowledge and skills necessary to assess and manage patients with varying levels of suicidality. Accordingly, a working knowledge of, and fluency with, terminology surrounding suicidality is required. Assessment (including screening) involves exploring the patient’s overall risk profile, including chronic/predisposing factors, the acute/potentiating factors, and protective factors. Subsequently, the hospitalist must determine whether the patient’s overall suicidel risk is at or above baseline. Finally, the hospitalist must devise appropriate management to address the patient’s suicide risk.

Assessment of Suicidality: What the Hospitalist Should Know

Patients who may not overtly express suicidality but are at increased risk for suicide and should be assessed

Patients who express suicidality while hospitalized

Patients admitted after a suicide attempt

Patients who are admitted after suicide attempts are the most conspicuous examples of suicidality and because of this receive the most attention in our literature. However, hospitalists will see many more patients silently at risk for suicide than those who are admitted for overt suicide attempts. Many hospitalists do not detect the underlying increased risk for suicide and therefore do not inquire further. This chapter addresses the practical knowledge and skills required to assess suicidality in any hospitalized patient. This information can be applied in most commonly found situations where suicidality is suspected. The hospitalist can be a first line of defense against suicide by accurately assessing and treating the hospitalized patients who are at increased risk for suicide.

What Key Words and Concepts Are Required to Assess Suicidality?

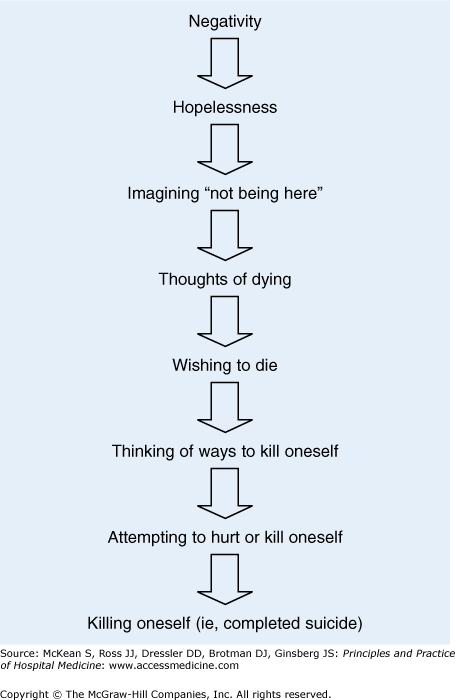

The terminology used to describe thoughts and actions related to self-harm is often confusing for health care professionals. The following construct (Figure 229-1) frames the essential vocabulary and concepts, defines key terms, and describes an easily accessible construct for suicidality.

The terms suicide, completed suicide, or “successful” suicide all refer to the actual act of killing oneself. A suicide attempt is an act of deliberate self-harm with the intent to kill oneself. However, the act may not seem deliberate (eg, taking too many pain medications) so the degree of intent (ie, the wish to die) may be hard to ascertain from the patient. The degree of lethality (ie, the likelihood of completion) is typically not hard to determine but should be taken in the context of the patient’s intent. The combination of the questions of intent and lethality lead to the notion that suicidal ideation (thoughts of suicide) or suicidality (attraction to suicide) are part of a spectrum of thoughts or feelings ranging from hopelessness to imagining “not being here,” to specific plans for self-harm, to acting on suicidal plans. (See Table 229-1 for a list of risk factors for suicide.) Circumstances in the life of the patient help the clinician to ascribe meaning to a suicide attempt. Obviously, if the individual says that he or she wrote a note and jumped off a bridge that is a clear attempt to complete suicide. However, if the individual says that he or she took a handful of ibuprofen after breaking up with a significant other, this may indicate a “cry for help” or an immature expression of pain.

| Chronic/Predisposing | Acute/Potentiating | Protective |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Hopelessness and associated emotions are some of the most consistent markers for severity of a psychiatric disorder, particularly mood disorders. While suicidality in some form is frequently present in severe psychiatric disorders (eg, major depression), completed suicide is relatively rare. In the United States, over 15 million people suffer with depression within a given year, and many will think about suicide, but fewer than 30,000 people will actually complete suicide from the total general population. Despite decades of study documenting epidemiologic correlations with completed suicide (ie, risk factors), there is no effective screening approach that accurately predicts completed suicide. Most leaders in suicide research note that suicide is not predictable and go on to advise the clinician that the clinical goal is not to predict but to fully assess.

Chronic and Predisposing Risk Factors for Suicide

Completed suicide has a base-rate of 12 per 100,000 in the general population. The most studied predisposing epidemiologic factors related to suicide risk are gender, race, and age. These predisposing chronic risk factors are fixed and therefore establish a baseline risk for suicide. In these categories men are at least four times more likely to complete suicide than women. However, women are about 10 times more likely to attempt suicide or make suicide gestures. Whites and Native Americans have significantly higher suicide rates than African Americans, Hispanics, or Asians. In the United States, white men commit 73% of suicides. Age is also a significant risk factor. Suicide rates dramatically increase in the seventh decade of life, especially for men.

Substance abuse, especially severe alcoholism, is a chronic risk factor. For some alcoholics in later life, when the social effects of chronic use have accumulated (isolation, alienation), a sudden or significant change (medical disease, divorce, loss of a job, death of a loved one) carries a particularly high risk for suicide. On the other hand, alcohol intoxication is an acute risk that quickly passes after the patient is sober.

The presence of a psychiatric disorder can pose acute and/or chronic risk for suicide depending upon the patient’s history and the acuity of the symptoms. Although a major mental disorder is associated with more than 90% of suicides, this likelihood is difficult to determine because the vast majority of the data on this subject is obtained retrospectively. However, of people with psychiatric conditions who complete suicide, depression accounts for 50%, alcohol and drug abuse 20–25%, and schizophrenia or bipolar disorder 10%. Other psychiatric disorders also increase the risk for suicide, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic disorder, and personality disorders that are characterized by impulsivity. In general, all psychiatric disorders carry a greater risk for suicide when compared with the general population.

When inactive symptoms of the disorder (ie, during remission or recovery) become reactivated (ie, during relapse or recurrence), the chronically elevated baseline risk for suicide is acutely increased. Knowing where the patient falls longitudinally within the progression of their disorder also helps the clinician assess risk. For example, patients early in the course of schizophrenia carry a greater risk than later. Most suicides in people with schizophrenia (60%) occur within six years of the first hospitalization.