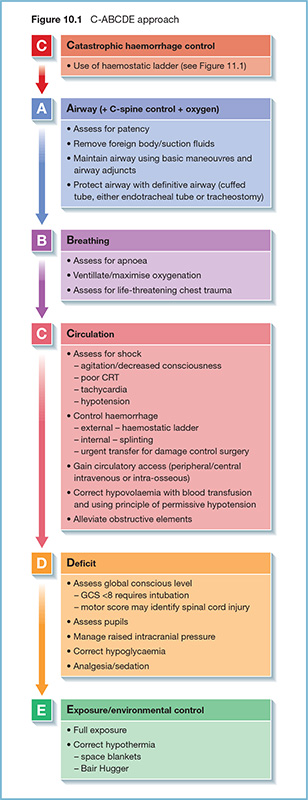

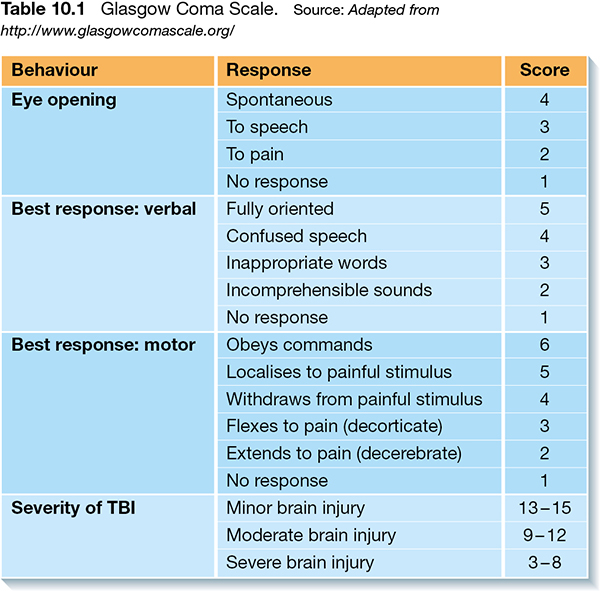

10 The primary survey forms the rapid initial assessment of the acutely unwell patient in any context, and in the case of major trauma is directed exclusively at identifying and treating immediately life-threatening injuries. The systematic, stepwise approach of C-ABCDE (Figure 10.1) ensures that pathology is addressed in the order of speed of fatality; airway compromise will kill more quickly than hypoglycaemia. Equally as important is the need to reassess the patient constantly from the beginning each time an intervention is made, as pathology rapidly evolves. Initial assessment is a repeated dynamic process. As ever in the pre-hospital phase, the clinician will already have a good idea of the likely pathology and provisional management plan before even reaching the patient, based on information gleaned from the initial callout history and reading the scene on arrival. Increasing experience of major trauma in combat has led to the recognition that even before airway obstruction, catastrophic external arterial bleeding will lead to rapid exsanguination and death. This is particularly common in traumatic limb amputation, where arteries are often incompletely transected and hence unable to fully retract and constrict to limit haemorrhage. The ladder approach to significant bleeding enables rapid haemostatic control. If the patient is talking, the airway is presumed clear. If the patient is not talking, look, listen and feel for breathing while simultaneously feeling for a central pulse. If the patient is not breathing and a pulse is absent, manage cardiac arrest according to cause. If the patient is not breathing, open the mouth and look for obvious causes of upper airway obstruction, e.g. foreign body (remove if easily accessible), vomitus/blood (suction). Additional sounds such as snoring imply partial upper airway obstruction due to loss of oropharyngeal tone and can be managed using the airway management ladder (manoeuvres/adjuncts/supraglottic devices/definitive airway); stridor, indicating distal upper airway obstruction, and significant orofacial trauma/inhalational injury may require a surgical airway. Manual in-line stabilisation of the cervical spine (C-spine) is of paramount importance to reduce risk of further damage/death from potential unstable C-spine fracture and goes hand-in-hand with assessment of the airway. After securing the airway, all patients must receive high flow oxygen to maximise oxygenation and minimise tissue hypoxia. The C-spine is typically secured with three-point immobilisation. At the same time, all monitoring should be applied to the patient.

The primary survey

Principles of rapid initial assessment

Catastrophic haemorrhage

Airway (+ cervical spine control + oxygen)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree