Chapter Three The pain experience

Chapter contents

Introduction

Pain can be described using a variety of terms and concepts. Pain is a noxious stimulus resulting from an actual or potential tissue damaging event that stimulates nociceptors. Nociceptors are receptors sensitive to a noxious stimulus or to a stimulus which would become noxious if prolonged (Seaman 1997). The experience of pain begins with the pain threshold, which is the smallest pain producing stimulus a person can perceive as painful, and pain tolerance, which is the maximum intensity of a stimulus that evokes pain and that a subject is willing to tolerate. An individual can modify pain tolerance and to a lesser extent pain threshold based on their perception of the pain sensation. There are also physiological mechanisms that can occur that modify pain threshold and pain tolerance. The pain experience can be altered by using changes in perception and activating physiological pain control mechanisms. These methods will be described in future chapters.

Some individuals experience pain due to hyperalgesia and/or sensitization. Hyperalgesia is an increased response to a stimulus which is normally painful. In other words the body overreacts to a pain producing stimulus. Hyperalgesia may include a decrease in both pain threshold and pain tolerance. Sensitization, a neurophysiological process resulting, is an increased responsiveness of neurons to their normal input or recruitment of a response to normally subthreshold inputs. In other words the body is interpreting nonpainful stimuli as pain. Like hyperalgesia, sensitization includes a drop in pain threshold and an increased sensitivity of neuroresponse. The nervous system may generate pain signals without any stimulus and increase the receptive field size. Pain tolerance is usually affected as well. Peripheral sensitization is an increased responsiveness and reduced threshold of nociceptors to stimulation of their receptive fields. Central sensitization is an increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the central nervous system to their normal or subthreshold afferent input, which may be due to dysfunction of the endogenous pain control system.

Figure 3.1 Biochemical, biomechanical, and psychosocial influences on health.

(Adapted from Chaitow & DeLany 2000.)

In simple terms hyperalgesia is like the saying making mountains out of mole hills, and sensitization is making something out of nothing. Knowing this terminology is all well and good in our task of understanding pain and being able to communicate with multidisciplinary heath care professions. However, these terms and descriptions do not describe what it is like to be in pain and to live the pain experience. Massage therapists must appreciate the mechanisms causing, enhancing, and creating the pain experience to competently use massage to help those experiencing pain. It hurts to be in pain whether that pain is acute or chronic, physical, emotional or spiritual, helpful or harmful. There are differences between harm and hurt. Pain hurts whether there is harm or not. Hurting is disempowering, fatiguing, miserable, and the foundation of suffering (Box 3.1).

Suffering

Massage can help reduce pain and suffering for a short period but the complex process of suffering requires multilevel intervention. The connection between physical and mental pain has been studied extensively by Matthew Lieberman, Naomi Eisenberger, and associates at the Social, Cognitive Neuroscience Lab at UCLA, Department of Psychology. Their research has shown that the pain and suffering that occurs when social relationships are damaged or lost and the pain experienced from physical injury share parts of the same underlying physiological processing system (Eisenberger & Lieberman 2004). Since physical and social pain rely on similar neural systems, factors that increase tolerance of the experience of social pain, such as social support, should also increase the tolerance to physical pain.

Grieving over the death of a loved one and being treated unfairly also activate these regions. Grief is one of life’s most painful experiences (Eisenberger & Lieberman 2005). In 1998, researchers suggested that the social attachment system uses opiate substrates of the physical pain system. This overlap in function results in pleasure when with those we care about and elicits distress when we are separated from the social attachment system. This pleasure/pain experience of connectiveness and separation piggyback onto the pre-existing pain system, borrowing the pain signal to signify and prevent the danger of social separation (Nelson & Panksepp 1998, Panksepp 1998). Ongoing studies by Lieberman and Eisenberger (Eisenberger, Lieberman & Williams 2003, Eisenberger et al 2004, 2006, 2007, Eisenberger & Lieberman 2005, Lieberman & Eisenberger 2005) continue to support that pain distress and social distress share neurocognitive function and increased social distress will increase sensitivity to physical pain and vice versa. Understanding this overlap in the neural systems underlying pain distress and social distress supports alternative ways to treat and manage chronic pain conditions. For example, rather than treating pain symptoms directly, it may be possible to reduce physical pain symptoms by addressing the social stressors that may go along with them.

Neuroanatomy of pain and pleasure

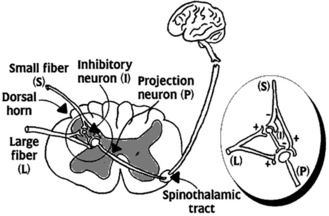

To appreciate how the experiences of pain occurs it is necessary to understand the neuroanatomy.

The reward or pleasure network consists of the ventral tegmental, ventral striatum, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and the amygdala. The brain’s reward circuitry consists of neural structures receiving the neurotransmitter dopamine. Major dopaminergic targets in the brain have been implicated in reward/pleasure processes (Lieberman & Eisenberger 2009).

According to pain experts Melzack and Wall (McMahon & Koltzenburg 2010), pain has three dimensions:

1. Sensory discriminative – thalamus and somatosensory cortex.

2. Motivational-affective – brain stem reticular formation, limbic system.

If massage therapy is going to be beneficial in pain management it must interact with the pain/pleasure anatomy and physiology. One of the greatest benefits of massage is that it feels good. Massage is pleasurable. The pain/pleasure system is like so many processes in the body. One dominates the other and then vice versa. When the agonist muscle is activated the antagonist muscle is inhibited. When the pain network dominates it is difficult to feel pleasure and also if the pleasure network is activated it is hard to experience pain (Fig. 3.3).