Fig. 12.1

Tunneled PICC: puncture site in the “yellow” zone, exit site in the “green” zone

Tunneling is a very simple procedure which can be performed with any PICC (of any material, of any company), using either a small needle cannula or a dedicated tunneler.

The needle cannula technique (Fig. 12.2) requires either a 16G cannula (for 3Fr PICCs) or a 14G cannula (for 4–5Fr PICCs). The same inexpensive 52 mm needle cannulas used for common peripheral i.v. lines are used. Soon after the insertion of the guidewire and/or of the micro-introducer-dilator into the vein, the incision on the skin is slightly enlarged by a #11 scalpel; after local subcutaneous anesthesia (few ml of ropivacaine or mepivacaine), the needle cannula is inserted in the skin few cm below the puncture site, exactly where the exit site has been planned (Fig. 12.2a); the needle is removed, the cone of the cannula is trimmed (Fig. 12.2b), and the catheter is threaded into the cannula (Fig. 12.2c). After the cannula is removed, the catheter is threaded into the micro-introducer (so called “anterograde” tunnelization). Both the exit site and the incision at the puncture site are sealed with cyanoacrylate glue (Fig. 12.3).

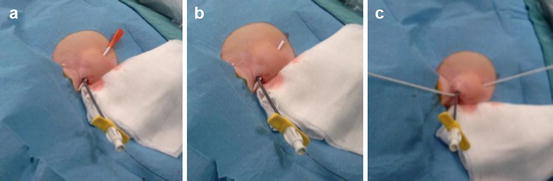

Fig. 12.2

Tunneling via a 14G needle cannula (description in the text)

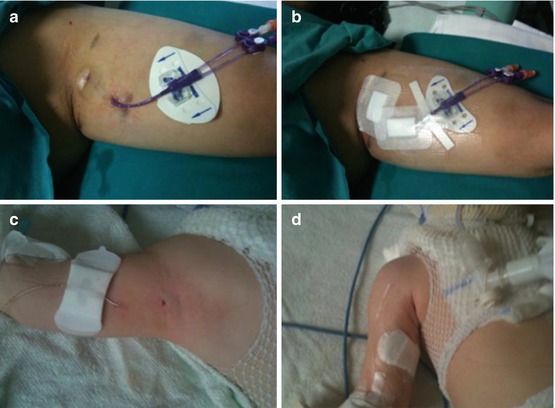

Fig. 12.3

Glue is used to seal both the puncture site and the exit site

Another possible option is the use of a dedicated PICC tunneler, available through different companies (Cook Medical, for instance). This is a metallic, non-sharp tunneler 12–15 cm long, which is inserted in the subcutaneous tissue through a small skin incision, several cm distally to the puncture site. Even in this case, it would be an “anterograde” tunnelization.

The anterograde tunneling maneuver can be done with any PICC, and it is the only option for PICCs which must be trimmed distally (i.e., the vast majority of PICCs commercially available). When dealing with PICCs which must be trimmed proximally (such as “Groshong PICC,” Bard, or “PICC Easy,” Vygon), the tunnelization is obviously retrograde and somehow easier.

Tunneling is particularly useful in pediatric patients, where veins are usually of reduced size and PICC placement is possible only by choosing veins very close to the axilla.

In summary, tunneling allows a “high” puncture of the deep veins of the arm, with several advantages:

It increases the indications of PICCs.

It allows PICC use in situations where tunneled catheters are explicitly recommended by national guidelines or by hospital policies (such as in the UK, where the guidelines of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology recommend that in bone marrow transplant, patients only tunneled catheters should be used).

It reduces the risk of catheter-related bloodstream infection (since it reduces the extraluminal contamination of the catheter).

It reduces the risk of thrombosis (since it allows to cannulate larger veins).

Also, if a cuffed PICC is used (such as Pro-Line, Medcomp), the PICC becomes a long-term venous access device, since the coupling of tunnel + cuff protects from extraluminal contamination and increases the stability of the catheter, making it less prone to dislocation.

Tunneling of PICCs has been extensively used in recent years by our PICC team (Catholic University Hospital, Rome, Italy) and by several clinical groups all over the world (Gail Egan and coworkers, USA; Michele Di Giacomo and coworkers, UK; Gloria Ortiz Miluy and coworkers, Spain), with very good clinical outcomes:

It is technically easy and safe for the patient.

Patient compliance is very good.

With a proper technique of tunnelization (i.e., expansion of the subcutaneous tissue by local anesthetic or by saline infusion; use of blunt tunneler), the occurrence of hematomas is very unusual, even in patients with coagulation disorders.

Tunneling does not conflict with the adoption of the method of intracavitary ECG for tip location, though when using a cuffed catheter, pre-insertion landmark-based estimate of the length of the catheter should be particularly accurate, so as to achieve simultaneously a correct placement of the tip at the cavo-atrial junction and a correct position of the cuff inside the tunnel, at no less than 2 cm from the exit site, as recommended by the current guidelines.

Tunneling is of great value also for PICCs inserted in atypical or “off-label” veins, as it will be discussed in the next paragraphs.

12.3 Atypical or “Off-Label” Site of Insertion

Though the IFU of most commercially available PICCs usually take into consideration only the cannulation of the basilic vein, the brachial veins, or the cephalic vein, PICCs can be inserted with relevant clinical advantages in many other veins which can be punctured and cannulated by ultrasound guidance.

12.3.1 Axillary Vein at the Upper Arm or at the Axilla

In some cases, as described above, basilic and brachial veins may be unavailable for PICC insertion (either because too small or occluded by thrombosis). This typically happens in infants and children or in skinny, malnourished aged patients or in patients with history of multiple PICC placements. In such cases, the axillary vein can be safely punctured and cannulated in its extrathoracic tract, either in the very proximal upper arm or directly in the axilla. Of course, in these situations tunneling is mandatory. When the axillary vein is punctured at the arm, tunneling is more appropriately performed so that the exit site might be located in Dawson’s “green” zone (Fig. 12.4); when punctured at the axilla (typically, in children), the catheter is preferably tunneled towards the thoracic area (Figs. 12.5 and 12.6).

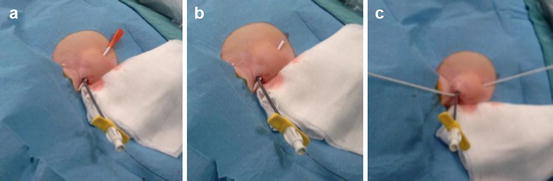

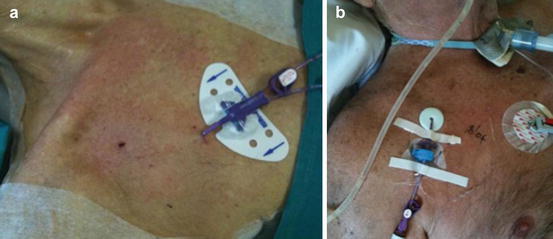

Fig. 12.4

Tunneled PICC in an adult (a, b) and in a pediatric patient (c, d)

Fig. 12.5

Axillary cannulation and tunneling to the thoracic area in a child

Fig. 12.6

Axillary cannulation and tunneling to the thoracic area in a neonate

The advantages of PICC placement into the axillary vein are intuitive, and they have been already discussed when presenting the advantages of tunneling (reduction of infection risk and thrombotic risk; enlargement of the indication to PICCs even in patients whose basilic and brachial veins are not adequate).

12.3.2 Axillary Vein in the Infraclavicular Area

PICCs can also be inserted into the axillary vein in its thoracic tract and specifically in the infraclavicular area. This is indicated in adult patients who have specific bilateral contraindication to the cannulation of veins at the arm. The technique is actually the same as the one described for the traditional puncture and cannulation of vein at the arm:

Choice of a catheter of appropriate size; since the axillary vein is usually quite large in the infraclavicular area (>6 mm), this is not a critical issue: most PICC of 3-4-5 or 6Fr will fit easily.

Ultrasound-guided venipuncture (visualization of the vein in short axis + “out-of-plane” puncture; in expert hands, visualization of the vein in long axis + “in-plane” puncture is also an option).

Modified Seldinger technique, using the micro-introducer-dilator provided in the kit.

Ultrasound scan of the ipsilateral internal jugular vein, so as to rule out a wrong direction of the catheter.

Verification of the correct location of the tip by the intracavitary ECG method.

Sutureless stabilization of the catheter at the exit site.

Tunneling may be sometimes required, for instance, when the puncture site appears to be too close to the tracheostomy or to skin lesions of the infraclavicular area (Fig. 12.7).

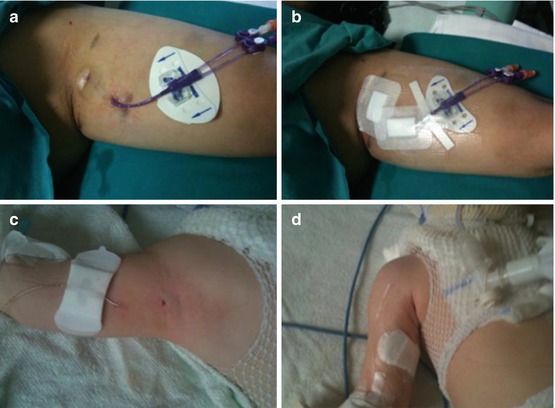

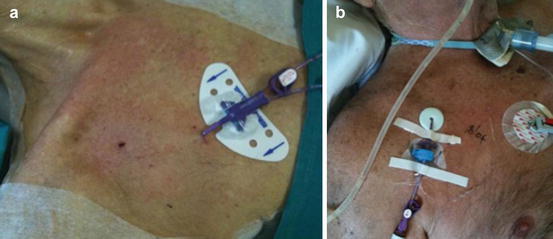

Fig. 12.7

PICCs inserted in the axillary vein, tunneled (a) and non-tunneled (b), in adults

Obvious contraindication to axillary venipuncture are morbid obesity (the vein might be far too deep), hypovolemia (the vein might be of small size or collapsed during breathing), or previous axillary/subclavian thrombosis.

The term “peripherally inserted central catheter” may not be accurate anymore in this situation, since the ultrasound-guided approach to the axillary vein is considered a direct central access. Though the “off-label” use of catheters commonly marketed as “PICCs” has many interesting clinical advantages, if compared to the use of standard CVCs:

The micro-introducer kit provided with the PICC is particularly appropriate for axillary venipuncture, since it includes a 21G echogenic needle (less traumatic than the 18G–19G needles usually provided in the CVC kits), a floppy straight tip 0.018″ nitinol guidewire (which is the wire most likely to pass uneventfully the curve of the subclavian vein at its passage below the clavicle).

The length of the PICC (50–60 cm) makes it ideal for any possible tunnelization, after proper trimming.

Also, when the axillary vein is cannulated on the left side in a normal adult, the estimated length of the catheter between the exit site and the cavo-atrial junction is longer than 20–22 cm; this implies that only CVCs 25 cm long (or longer) should be used when cannulating the left axillary vein, though they might be too long when used on the right side, so that only 20 cm CVCs should be used in this case; the PICC – which can be trimmed of any desired length – has obviously a net advantage in this regard.

Most PICCs used today are of power-injectable polyurethane, which has many advantages in terms of clinical performance [6] if compared to the standard polyurethane of most CVCs.

PICC kits are usually equipped with many accessories (micro-introducer kit, sutureless device, needle-free connectors, etc.) which are usually absent in most CVC kits.

In our institution, the majority of central venous access for intrahospital use is achieved by PICC placement at the arm. When this is contraindicated, our second best option is the “off-label” placement of a PICC – as a direct central line – into the axillary vein in the infraclavicular area. In our clinical experience, as presented at the 2010 annual conference of AVA (Association for Vascular Access), most of these lines can be inserted by specifically trained nurses [7].

12.3.3 External Jugular Vein

The off-label insertion of PICCs in the external jugular vein in its superficial tract over the sternoclavicular muscle may be more easily accepted as an actual “peripheral insertion,” since this vein is usually considered as a “peripheral” vein.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree