Key Clinical Questions

What elements of the history and examination are most useful in lesion localization?

What elements of the neurologic examination can be assessed at the bedside without formal testing?

What tests can be performed on the unresponsive patient?

What scales and tools are used to document the findings of the neurologic exam?

Introduction

The neurologic examination is central to the evaluation of patients with neurologic complaints. It relies heavily on the history and on directed, hypothesis-driven physical testing. The neurologic examination can provide a great deal of information quickly. Even when it is not diagnostic, it guides the appropriate choice of imaging and ancillary testing. However, if it is performed in a cursory fashion, one can easily miss clues to a diagnosis that may not be apparent on imaging. This chapter reviews the essential elements of the neurologic examination in evaluating patients in the hospital.

Importance of the History

The history allows the hospitalist to narrow the range of diagnostic testing and perform a more focused neurologic examination.

A 57-year-old right-handed man presents with an episode of syncope while typing a manuscript. He recalls no prior episodes but does have a history of well-controlled hypertension and hyperlipidemia. You are called by the emergency department physician to admit the patient to telemetry and rule out an arrhythmia. The patient recalls similar episodes that he has had for as long as he can remember. They were bothersome during school but are brief and infrequent now. He also notes that they were worse when he was tired. The patient’s physical examination was unrevealing. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his brain was negative, but an electroencephalogram (EEG) showed occasional epileptiform discharges from the left hemisphere. The patient was begun on anticonvulsants at a very low dose and has had no further episodes. |

When taking the neurologic history, the focus should be, first, on localizing the lesion and, second, on developing a differential diagnosis. Missed diagnoses are common in neurology when jumping to a conclusion before establishing where the problem may lie. Tempo is helpful: is the process waxing and waning, as in delirium, steadily progressive, as in dementia, or in a stepwise decline, as from multiple strokes? During which activities is weakness more pronounced: rising from a chair, carrying heavy loads, or brushing or washing hair, as with proximal weakness, or opening a jar, opening a car door, or turning a key in a lock, as with distal weakness? Is the sensory phenomenon negative, such as the numbness resulting from a stroke, or positive, such as tingling from nerve root compression?

Without a detailed history, this patient might have been admitted to telemetry and had extensive and inappropriate cardiac investigations. He might have been discharged with the diagnosis of unexplained syncope and gone on to have a seizure at an inopportune time. With a careful history, he leaves instead with a correct diagnosis and life-altering therapy.

Localizing the Lesion

A major goal in neurology is to localize the lesion causing the patient’s symptoms. Diagnosis in neurology, as in other domains of medicine, relies partly on pattern recognition. Important patterns include the hemiparesis and language deficit of a dominant middle cerebral artery stroke, the cranial nerve findings and crossed body involvement of a brainstem stroke, the distal neuropathy of diabetes, the ascending weakness of Guillain–Barré syndrome, and the diurnal variation of ptosis and diplopia in myasthenia gravis. However, many signs and symptoms in neurology are nonspecific and may be produced by lesions in more than one anatomical site.

A 27-year-old man who has previously been healthy complains of strange sensations. You note that his mental status is normal, as are his cranial nerves, with the exception of an afferent papillary defect on the right. He has full strength, with increased muscle tone diffusely, and developed a mild right-sided foot drop about a year ago, for which he never sought treatment. Sensation is normal except for much of his left hemithorax. Reflexes are mildly hyperactive, and a Babinski sign is present. |

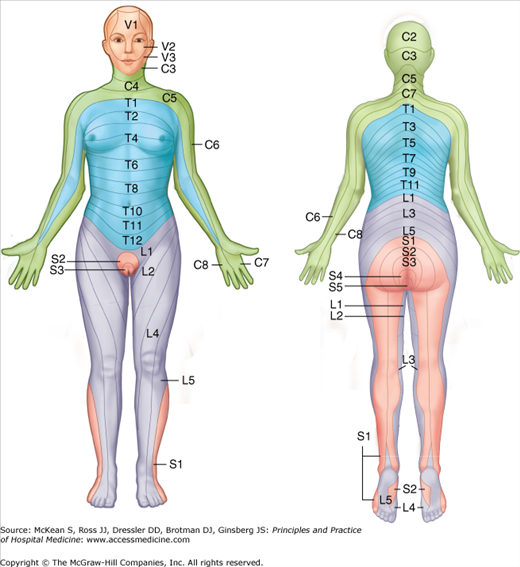

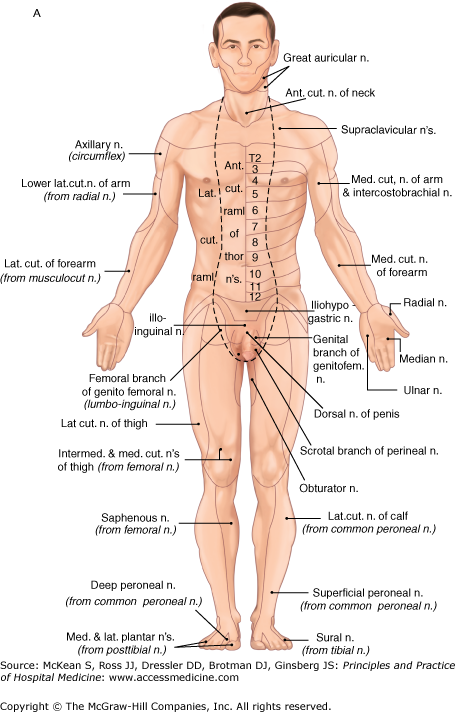

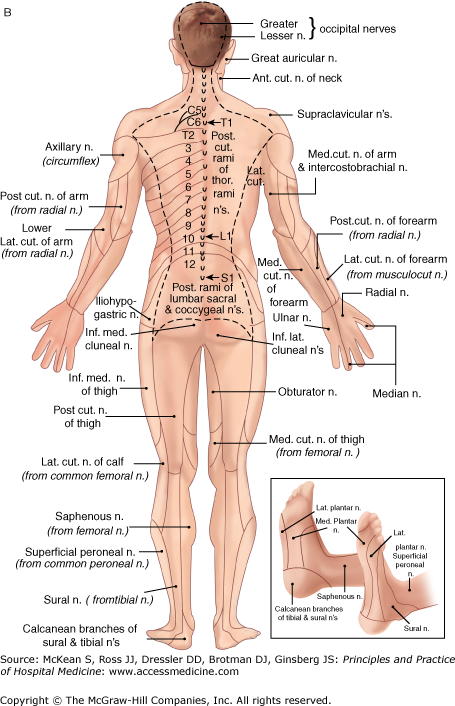

A fundamental distinction in neurologic disease is deciding whether a central or peripheral lesion is responsible. Central lesions affect the brain and spinal cord, and peripheral lesions affect the anterior horn cells, peripheral nerves, neuromuscular junctions, or muscles. Localizing a lesion to the central or peripheral nervous system avoids excessive, “shotgun” imaging, resulting in potential morbidity and inflated costs. In the case above, there are elements that are likely central (afferent pupillary defect, hyperactive reflexes, increased tone, and Babinski sign) and others that could be either (foot drop). It would be helpful to further define the abnormal sensation using dermatome and peripheral nerve maps (Figures 207-1 and 207-2). If the new abnormality does not conform to the distribution of a peripheral nerve or dermatome, a central lesion is probable, and neuroimaging is indicated. Ordering an electromyogram (EMG) in this setting would be inappropriate and of low yield.

In this case, the patient has lesions that are separated in space (different locations in the CNS) and time (old foot drop, new altered sensations). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is ordered, which demonstrates multifocal T2 hyperintensities that particularly involve the periventricular white matter, consistent with demyelinating lesions of multiple sclerosis.

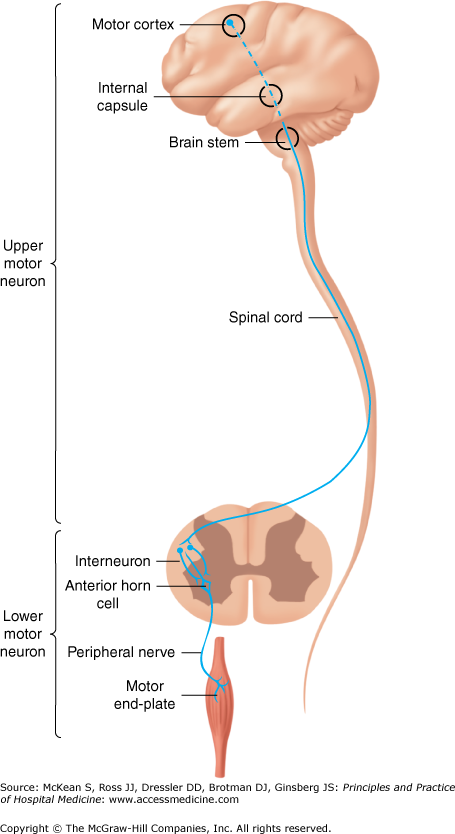

When patients have weakness, it is helpful to localize the lesion to either the upper or lower motor neuron (Figure 207-3). Severity of weakness does not distinguish between these anatomical sites, but examination of tone, reflexes, and other elements of the exam do (Table 207-1). When upper motor neuron weakness is present, the lesion must be in the brain or spinal cord. Lower motor neuron weakness may have multiple localizations (Table 207-2), none of which can be discerned through imaging studies of the brain and spinal cord; key next steps may include EMG and nerve conduction studies (NCSs).

| Upper Motor Neuron | Lower Motor Neuron | |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern of weakness | Pyramidal | Variable |

| Function/dexterity | Rapid alternating movements slow and clumsy (indicates disease in cerebellar or corticospinal tracts) | Impairment of function is mostly due to weakness |

| Tone | Increased | Decreased |

| Tendon reflex | Increased | Decreased, absent, or normal |

| Other signs | Babinski sign, other central signs (eg, aphasia, visual field cut) | Atrophy (except with problems of the neuromuscular junction) |

| Motor Neuron Disease | Neuropathy | Neuromuscular Junction | Myopathy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weakness pattern | Variable | Distal | Diffuse | Proximal |

| Deep tendon reflexes | Increased, normal, or decreased | Decreased or absent | Normal or decreased | Normal or decreased |

| Atrophy | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Fasciculations | Yes | Sometimes | No | No |

| Sensory symptoms and signs | No | Yes | No | No |