(1)

Division of Trauma and Critical Care, R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, Baltimore, MD, USA

Keywords

LungTraumaResectionThoracotomyDamage controlTractotomyPneumonorrhaphyPulmonary hilar twistNon-anatomic pulmonary resectionIntrapericardial exposureIntroduction

A majority of patients with chest trauma, from either penetrating or blunt injury, can be managed nonoperatively with either observation or a chest tube [1–3]. When surgery is indicated, the purpose of pulmonary resection is to either control lung bleeding or excise injured tissue [4]. Patients who require thoracotomy following blunt trauma often have more severe injuries requiring a more complex operation and are associated with higher mortality [1–5].

Indication for urgent or emergent thoracic surgical exploration includes shock with a penetrating thoracic injury, chest tube output in excess of 1,000–1,500 cc after chest tube placement, continued chest tube output or ongoing bleeding greater than 200–300 cc/h, massive air leak, and cardiac tamponade [2, 6]. High chest tube output is indicative of continued bleeding that requires surgical control while large air leak is concerning for a major tracheobronchial injury. Bronchoscopy is often necessary to completely or thoroughly evaluate a major airway injury in order to help plan the appropriate operation and incision. Up to a third of patients who require thoracotomy for traumatic hemorrhage will also require a pulmonary resection [1]. Managing patients with severe chest trauma requires an understanding of thoracic surgical procedures, which can be effectively employed in unstable actively bleeding patients. The first issue is to determine what incision or approach should be utilized and the second consideration is to determine what procedure should be performed.

Incision

There are various options available for surgical exposure, and it is important to be familiar with the advantages and limitations associated with each approach. The thoracic incision that is ultimately utilized should be versatile enough to address potential injuries in adjacent locations including the neck and abdomen [7]. While covered elsewhere, a few comments may be helpful.

Anterolateral Thoracotomy

This incision is rapid, avoids the time-consuming positioning associated with the traditional posterolateral thoracotomy, and does not require a sternal saw. It provides excellent exposure to the anterior hilum. This incision is the most common approach to the patient in extremis undergoing a salvage resuscitative procedure. It is also utilized in patients undergoing an exploratory laparotomy who decompensate and necessitate an emergent thoracic exploration. Finally, this incision permits an extension into the contralateral hemithorax providing wide exposure of both hemithoraces and the anterior mediastinum (clamshell thoracotomy). Limitations include limited exposure of the posterior mediastinum especially the esophagus, aorta, and posterior aspect of the lung.

The inframammary crease is the landmark for the incision. The pectoralis muscle is divided followed by the intercostal muscles within the desired interspace, often the fourth or fifth. The internal mammary artery and vein are in close proximity to the sternum, and they should be preserved if possible.

Bilateral Anterior Thoracotomies

Also known as a clamshell thoracotomy, it is performed by starting with an anterolateral incision and extending it across the midline. It provides wide exposure of the anterior mediastinum, bilateral lungs, and pleural cavities. It does require either a Lebsche knife, sternal saw, or Gigli saw to divide the sternum horizontally. Retractors are placed to enhance exposure. This incision requires the identification and ligation of both internal mammary vessels.

Posterolateral Thoracotomy

This is the classic incision utilized for thoracic surgery and provides the best exposure of the thorax, especially the entirety of the lung. It does require more extensive preparation. It should only be utilized if the patient is hemodynamically stable, and the injury is confined to a single hemithorax [8]. Correct positioning of the patient is essential and includes lateral positioning with the iliac crest at the level of the table break and rolls or an inflated bean bag to assist in stabilization. An axillary roll should be placed, while bending the lower leg to about a 90° angle, keeping the upper leg straight with a pillow in between. The upper arm is placed up toward the head, flexed at the elbow, and secured to an arm rest. Often one lung isolation is required and achieved with either a double lumen endotracheal tube or bronchial blocker placed by anesthesia. The bed is flexed to help expand the intercostal spaces.

The incision extends from the level of the mid-scapula in between its edge and the spinous processes, swinging down and anterior through a point about 2–3 cm below the tip of the scapula and then anteriorly to the anterior axillary line and into the inframammary fold as needed. The latissimus dorsi muscle is then divided. The serratus anterior muscle is identified, and the adjacent fascia divided in an attempt to preserve this muscle. A scapula retractor is utilized to elevate the scapula and help identify the desired interspace by counting the ribs. The thorax is entered in the desired interspace by dividing the intercostal muscles with the electrocautery in a posterior to anterior direction along the superior edge of the inferior rib. A Finochietto retractor is then inserted and carefully opened.

All incisions are closed after placing chest tubes, which are taken out through separate stab incisions and secured to the skin. The ribs are reapproximated with interrupted intercostal sutures. The muscles are sutured to the adjacent fascia, followed by a subdermal and skin layer.

Sternotomy

This incision provides excellent exposure to the anterior mediastinum for quick access to the heart, great vessels, pericardium, and thymus. Thus, it is not a primary incision for pulmonary injuries. Injury to the lung may occur with an injury best repaired via a sternotomy. It does provide adequate exposure for many pulmonary procedures except for access to the left lower lobe.

The standard incision is from the jugular notch down to the xiphoid process. The ligamentous tissue just superior to the jugular notch should be divided with electrocautery, and the retrosternal space bluntly mobilized digitally. The midline of the sternum is identified, scored, and then divided with a sternal saw while respirations are temporarily held. After inspecting the sternal edges and controlling the sternal bleeding, a sternal retractor is placed. After placing chest tubes, the incision is often closed with sternal wires to reapproximate the sternum and Vicryl suture in layers for the soft tissue.

Operative Technique with Personal Tips

Emergent thoracic trauma cases present challenges to achieving the isolated lung ventilation routinely employed in elective thoracic surgery. However, in patients who can be temporarily stabilized, placing a double lumen tube can be very helpful. Having an experienced anesthesia team helps keep time to a minimum. However, most operations in the trauma setting are performed with a single lumen endotracheal tube in patients with tenuous respiratory function. Temporary holding of ventilation and manual compression of lung parenchyma are some techniques that may facilitate the surgeon in overcoming this challenge of the lack of isolated lung ventilation [7].

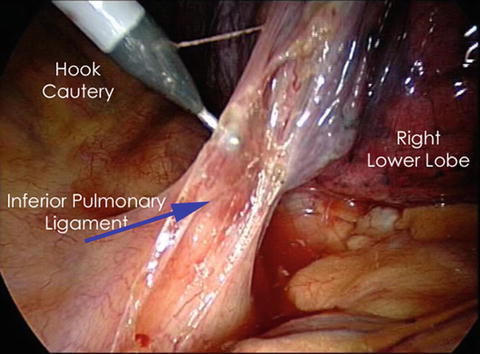

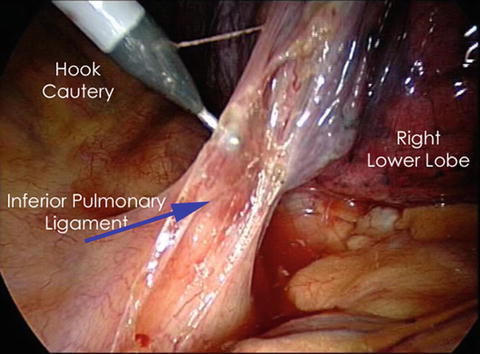

Once the chest is entered, accumulated blood should be cleared and the injury assessed. The inferior pulmonary ligament should be divided to give maximal mobility to the lung (Fig. 9.1). Associated chest wall and/or vascular injuries should be identified before a definitive plan is made. One should assess the adequacy of exposure. If exposure is not adequate, the incision should be widened and/or a counter incision made to facilitate adequate exposure. If a sternotomy has been used, anterolateral thoracotomy should be considered. If an anterolateral thoracotomy has been used, converting to a clamshell should be considered. One should avoid struggling through an inadequate incision.

Fig. 9.1

Dividing the inferior pulmonary ligament. Copyright 2009, used with permission from CTSNet (www.ctsnet.org). All rights reserved.

Formal pulmonary resections for trauma such as lobectomy and pneumonectomy are associated with high mortality rates. Other less morbid “lung-sparing” techniques have evolved and include pneumonorrhaphy, tractotomy, and non-anatomic pulmonary resections. These less extensive procedures often utilize staplers, have shorter operative times, decreased blood loss, and less parenchymal loss, all of which may contribute to improved outcomes [9, 10]. One should still be familiar with all the possible surgical options but be prepared to perform a more extensive resection if lung-sparing attempts fail [11]. When performing any type of lung procedure, adequate exposure is essential. This is accomplished by choosing the most appropriate incision as described earlier and by complete mobilization of the lung after entering the thoracic cavity. This includes lysing any pulmonary adhesions [7].

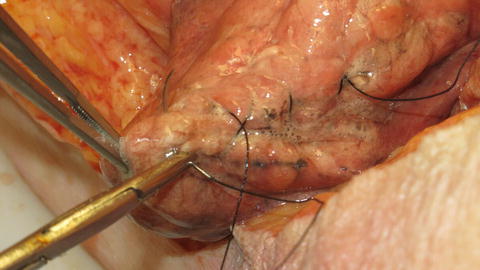

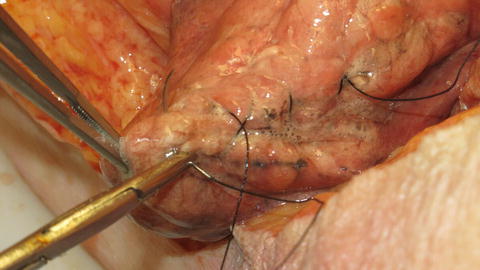

Pneumonorrhaphy

This is a common technique in which hemostasis is achieved and air leak sealed by direct suturing of the actively bleeding pulmonary injury (Fig. 9.2). A running locked suture technique can be employed to help achieve hemostasis [12]. This should only be utilized on peripheral superficial pulmonary injuries. Entry and exit injuries from penetrating wounds should usually not be oversewn since hemostasis may not actually be achieved. The risk is that only visible bleeding may be controlled while active hemorrhage may remain hidden, with continued, uncontrolled bleeding into the underlying pulmonary parenchyma risking the formation of an intrapulmonary shunt, bronchopulmonary fistula, aspiration, pneumonia or infection, and ARDS respiratory failure [2, 9, 13, 14].

Fig. 9.2

Pneumonorrhaphy.

Tractotomy

This is a technique to rapidly control deep pulmonary parenchymal bleeding that does not involve the hilum or central bronchial vascular structures. It helps avoid a pulmonary resection, which was historically performed for such injuries, thus preserving lung tissue, while preventing retention of a parenchymal hematoma [1, 11, 14, 15]. The sites of the entry and exit wounds are identified, and lung clamps are placed along the injury tract (Fig. 9.3). A GIA or TA stapler is placed through these openings and fired, which opens the injury tract. Bleeding vessels and injured airways are identified and ligated with absorbable suture. After controlling bleeding and air leaks, the pulmonary tissue can be closed with a running locked suture, or if feasible, the edges can be stapled [8, 12, 14, 15].