Chapter 5 The ill child – assessment and identification of primary survey positive children

Introduction

Sick children present particular challenges to the pre-hospital practitioner. The anatomy of children is different to that of adults, and this can result in differences in the presentation and severity of a range of conditions. Paediatric physiology also differs from that of adults, and although this means children often compensate very well for significant clinical illness it also carries the risk that a severe problem will be overlooked or underestimated. When compensatory mechanisms fail in children, they often do so rapidly, catastrophically and irreversibly. The index of suspicion of the pre-hospital practitioner must therefore be higher than for an adult when assessing the ill child, and the threshold for hospital admission will consequently be lower than for an adult patient with similar findings. The emphasis should be on detecting and treating the seriously ill child at an early stage to prevent deterioration rather than to attempting to cope with a decompensated, critically ill child.

The paediatric section of this text is divided into two chapters. The objectives of this first chapter are outlined in Box 5.1.

Whilst this chapter concentrates on identifying or ruling out potentially time critical problems, it should be remembered that many children have problems that are not immediately life threatening. Common illnesses affecting children are covered in Chapter 6.

Significant anatomical and physiological differences between children and adults

Airway

In infants (aged 0–1 years) and children (aged 1–8 years) the head is proportionately larger and the neck shorter than in adults. This can lead to neck flexion in the recumbent baby or child, precipitating airway obstruction. The trachea is also more malleable, and this coupled with the large tongue can result in airway obstruction if the head is over-extended when attempting to open the airway by positioning, particularly in infants. Milk teeth may be loose, and the smaller size of the mouth increases the risk of dislodgment or tissue damage. Compressing the surface of the skin below the lower jaw in an attempt to open the airway can result in the tongue being displaced and worsening obstruction. Infants less than 6 months old are obligate nasal breathers. The epiglottis is horseshoe shaped and the larynx higher and more anterior, the tracheal rings are soft and not fully formed, and the cricoid cartilage is the narrowest part of the upper airway. All have implications for airway management and the consequences of related illnesses.

Breathing

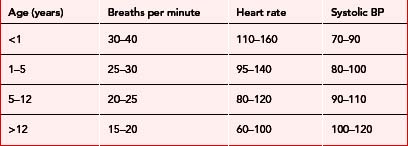

The total surface area of the lungs and the number of small airways is limited in infants and children and small diameters throughout the respiratory system increase the risk of obstruction. Infants have ribs that lie more horizontally and therefore rely predominantly on the diaphragm for breathing. They are more prone to muscle fatigue and therefore respiratory failure. Increased metabolic rate and oxygen consumption contribute to higher respiratory rates than in adults (Table 5.1).

Circulation

Infants and children have a relatively small stroke volume but a higher cardiac output than in adults, facilitated by higher heart rates (Table 5.1). Stroke volume increases with age as heart rate falls, but until the age of two the ability of the child to increase stroke volume is limited. Systemic vascular resistance is lower in infants and children, evidenced by lower systolic blood pressure (Table 5.1). The circulating volume to body weight ratio of children is higher than adults at 80–100 ml/kg (decreasing with age) but the total circulating volume is low. A comparatively small amount of fluid loss can therefore have significant clinical effects.

Range of normal development in children, and assessment strategies

Infants

The developmental milestones of infants are outlined in Table 5.2. Remember, there may be wide variation in the age of attaining these milestones.

Table 5.2 Developmental milestones in infants

| Age (months) | Activity |

|---|---|

| < 2 | Predominantly sleeping or eating |

| Unable to differentiate between strangers and carers/family | |

| 2–6 | Spends more time awake |

| Starting to make eye contact | |

| May follow movement of toys/lights with eyes | |

| May turn head towards sounds | |

| Starts to vocalise sounds | |

| Active extremity movements | |

| May recognise caregivers | |

| 7–12 | Sits unsupported |

| Reaches for objects and puts them in mouth | |

| Recognises caregivers and afraid of separation from them; afraid of strangers |

When assessing an infant, the caregiver can be asked to hold the child and get down to ‘baby level’. It is a good idea to say the child’s name, speak softly and avoid sudden movements. The examination may be commenced by simply observing the child, and then ‘hands on’ examination can begin starting with the least upsetting steps. It is wise to adjust the order of the examination according to the child’s behaviour – for example, listening to breath sounds and counting the respiratory rate when the child is calm and certainly before doing anything that may be painful or distressing. Your hands and any instruments should be warm, and clothing should be removed only one item at a time to maintain body warmth and reduce fear.

Children

The developmental milestones for children aged 1–12 are outlined in Table 5.3.

Table 5.3 Range of normal behaviours in children aged 1 to 12 years

| Age (years) | Activity |

|---|---|

| 1–2 | Initially crawling and walking supported by furniture, then walking and running Feed themselves Plays with toys Starting to communicate with increasing vocabulary; will understand more than they can vocalise Independent and opinionated: cannot be reasoned with Curious but with no sense of danger Frightened of strangers |

| 2–5 | Illogical thinkers (by adult standards) May misinterpret what is said to them Fearful of being left alone, loss of control, and being unwell Limited attention span |

| 5–12 | Talkative Understand the relationship between cause and effect Pleased to learn new skills Older children may understand simple explanations about how their bodies work and their illness Fearful about separation from parents, loss of control, pain and disability May be unable to express their thoughts Desire to ‘fit in’ with peers |

The child can be observed from a distance initially whilst the history is being taken, and then approached slowly, preferably avoiding physical contact until the child is familiar with you. Children should remain with caregivers, and sit on their lap if they wish to do so. Young children respond to praise – admiring clothes or a favourite toy and recognising good behaviour are effective ways to win them over. They may be soothed by being allowed to play with their own toys or by being allowed to hold instruments such as a stethoscope. The caregiver can assist with the assessment, by removing clothes or holding an oxygen mask. Use of very simple words and toys can facilitate explanations to the child. Critical parts of the assessment can be undertaken whenever the child is at their most calm: consider examining from toes to head. A limited element of control can be given to the child, asking which part the child would like you to examine first. Do not lie to children and, in particular, never tell them something will not hurt if it will!