The History and Examination of Headache Patients

Jes Olesen

David W. Dodick

CLINICAL APPROACH TO PATIENT WITH HEADACHE

For patients with new-onset or progressive headaches, the approach is similar to that of other acute neurologic illnesses. Such headaches may be secondary and the efforts are directed at identification of the cause of the headache and providing treatment for the underlying condition. The approach to headaches that have been recurrent and present for more than 6 months is different.

Patients who present to a primary care physician or neurologist for the first time with a pure migraine or pure tension-type headache are straightforward and need no special approach except a careful history, neurologic examination, proper classification, and appropriate treatment. The general practitioner should know how to identify migraine without aura, migraine with aura, episodic tension-type headache, chronic tension-type headache, cluster headache, and chronic posttraumatic headache. When these conditions are not present, patients should be referred. Likewise, if the general practitioner is not successful after trying two acute or preventive treatments, the patient should be referred to a neurologist or a headache specialist.

Patients who are difficult to treat or who have a rare type of headache are best seen by a neurologist with a special interest in headache. This article is intended for neurologists and other doctors with such an interest. Therefore, we focus on a comprehensive approach that is suitable for difficult headache patients. Before these patients present to a specialist they have often seen several primary care and specialist physicians, have had numerous computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and have seen psychologists or psychiatrists, ear, nose, and throat specialists, ophthalmologists, or other specialists. They are often quite desperate because their headaches significantly impair their work-related productivity, and impose a significant burden on their social, family, and leisure activities. In many cases, past consultations have not resulted in a thorough history or neurologic examination and treatment results have been disappointing. Some of these patients are understandably alienated from the medical system.

The first task for the headache specialist is to display real interest in the patient and to make them understand that their problem is being taken seriously. In practical terms, this means taking an extensive general history and a detailed headache history, as well as performing a general and a neurologic examination with emphasis on headacherelevant aspects.

Even though migraine is a highly prevalent and disabling medical condition for which unambiguous operational diagnostic criteria are available (3), it is still frequently misdiagnosed. In a recent population-based study, 52% of the patients who fulfilled the International Headache Society classification criteria for migraine did not receive the correct diagnosis (13). Of those who received an inaccurate diagnosis, 42% received a diagnosis of sinus headache and 32% received a diagnosis of tension-type headache. Although the reason for such misdiagnoses is unclear and is probably multifactorial, the frequent presence of symptoms such as nasal congestion, lacrimation, rhinorrhea, and neck stiffness and pain during migraine attacks likely contribute to this problem (1). In addition, several common migraine triggers such as stress, changes in weather, and high altitude may lead a physician to one of these alternative diagnoses. Tension-type headache, even chronic tension-type headache, is also underdiagnosed (19).

GENERAL HISTORY

The family history of headache is important. This is especially true in migraine, where there is a 4-fold risk for

migraine in first-degree family members of patients with migraine with aura, and a 2-fold increase for migraine without aura. It should be remembered, however, that lifetime prevalence of migraine may be as high as 15 to 20%, which means that just by chance, in a typical family with seven first-degree relatives, there should be on one family member affected. Therefore, it is only when there is more than one first-degree relative affected that a family history can be called positive for migraine (18). For chronic tension-type headache just one affected first-degree relative is indicative of a genetic disposition. Episodic tension-type headache is so prevalent in the normal population that a family history is of no interest. The family history should also focus on diseases known to be comorbid with headache disorders such as epilepsy, allergy, depression, and anxiety disorders.

migraine in first-degree family members of patients with migraine with aura, and a 2-fold increase for migraine without aura. It should be remembered, however, that lifetime prevalence of migraine may be as high as 15 to 20%, which means that just by chance, in a typical family with seven first-degree relatives, there should be on one family member affected. Therefore, it is only when there is more than one first-degree relative affected that a family history can be called positive for migraine (18). For chronic tension-type headache just one affected first-degree relative is indicative of a genetic disposition. Episodic tension-type headache is so prevalent in the normal population that a family history is of no interest. The family history should also focus on diseases known to be comorbid with headache disorders such as epilepsy, allergy, depression, and anxiety disorders.

Many chronic headache sufferers who present to tertiary referral centers may be generally prone to other somatic pain conditions and psychophysiologic illnesses. Therefore, a careful history of past admissions and other pain-related illnesses are important. Admissions where no organic basis has been demonstrated may indicate the presence of a somatoform disorder or somatization disorder. It is important to go through complaints from all organ systems in patients with a chronic headache disorder. Quite often patients have had abnormal chest sensations leading to emergency room visits, but without any findings. Asthma may be comorbid, but attacks of dyspnea may be related to hyperventilation associated with panic attacks. Some patients have a long history of abdominal pain, pelvic pain, or even a lifetime history of pain involving several organ systems or body parts. This information is usually not given spontaneously, but can be elicited by direct questioning about specific past symptoms. Patients should also be questioned about previous consultations with psychiatrists or psychologists, so as not to overlook a major mood disorder that may be comorbid with migraine and may influence the choice of therapy.

The existence of other diseases, for example, diabetes, obesity, vascular disease, and allergic conditions, is important for the choice of treatment. Such conditions are often relative contraindications to the use of some prophylactic migraine drugs and may therefore influence the choice of treatment. The drugs used to treat other disorders may not be optimal and some, such as calcium antagonists, may aggravate migraine; others may be effective for both disorders. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for depression should be replaced by tricyclic antidepressants in headache patients.

The social history must be taken carefully. Most important are personal relationships to spouse or other partner and with children and parents. The loss of a loved one by death or divorce often coincides with worsening of a headache condition, but the patient may not notice this relationship. Recent job change, problems in relations to colleges or superiors, or simply being overburdened by work and domestic obligations often result in worsening of headache. As in other pain conditions, a situation of unsettled compensation claims or litigation makes it very difficult to treat the patient successfully. Addiction to coffee, tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drugs is also a bad prognostic sign and requires a special approach to the patient.

HEADACHE HISTORY

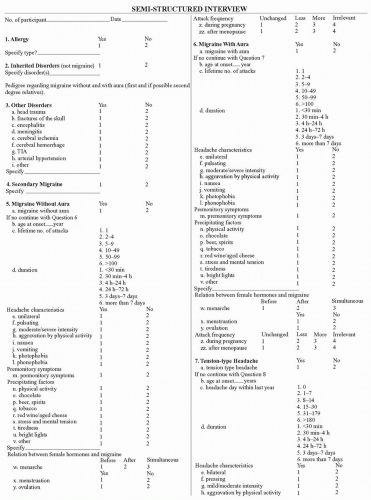

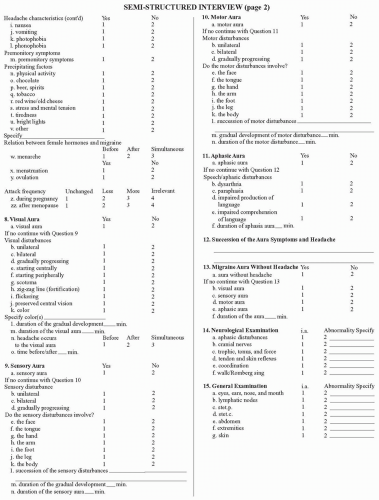

Taking the headache history may be time consuming, but it is the most important aspect in the evaluation of patients with a chronic recurrent primary headache disorder. First, it should be determined whether the patient consults for one or more than one headache disorder. In most cases, patients can correctly tell you whether they have one, two, or maybe three different kinds of headache. Some patients, however, consider mild migraine attacks, medium migraine attacks, and severe migraine attacks to be three different kinds of headache. Others consider attacks of tension-type headache and migraine without aura to represent a single kind. For the skilled interviewer, it usually only takes a minute or two to determine how many different kinds of headache are actually present. After that, it is essential to identify the characteristics of each of these types separately. This can be done in a more or less detailed fashion. For research purposes, we have developed and validated the semistructured interview shown in Figure 6-1 (17,18). This interview is done for each type of headache that a patient has. After repeated use, the interviewer becomes quite proficient and efficient with the use of this semistructured interview, allowing the collection of information in a systematic fashion. Ultimately, the use of such an instrument can significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy because it seeks to ask questions that are relevant for the classification of headache according to International Headache Classification (3). Most clinicians ask a lot of other questions just by tradition, but these questions are not necessarily helpful because they do not contribute to the differential diagnosis of the headaches. Finally, the prospective use of a diagnostic headache diary further increases diagnostic precision as discussed later in this chapter.

Primary or Secondary

A patient without a history of headache who experiences a headache of sufficient severity to warrant a medical consultation should be very carefully evaluated for a secondary cause. However, this recommendation is also important because patients who may have episodic tension-type or migraine headache are not immune to secondary headaches. These patients may come to medical attention to discuss an isolated headache or a new and progressive headache that is different than the headaches they have previously experienced. These patients frequently warrant further diagnostic testing in an effort to exclude secondary causes of concern based on the features of the headache.

In evaluating a patient who seeks a consultation in the office or urgent care setting regarding a problematic headache or a different type of headache, the intensity of the headache and the speed with which it reaches peak intensity are vitally important issues to address. Headaches that begin abruptly (thunderclap), with peak intensity within seconds suggest a vascular mechanism, for example, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, pituitary apoplexy, or carotid or vertebral artery dissection (4). Some patients may present with benign thunderclap headache that occurs spontaneously or during sexual intercourse, exercise, or after performing a Valsalva maneuver (e.g., cough, sneeze). However, these patients always require a careful initial diagnostic assessment with appropriate neuroimaging and lumbar puncture to exclude secondary causes. Patients who develop recurrent abrupt headaches during a particular activity (e.g., sexual intercourse) do not require a diagnostic evaluation if such a pattern has become clearly established. The rapid onset of some primary headache disorders such as cluster headache, short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform pain with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) syndrome, trigeminal neuralgia, and primarily stabbing headache (ice-pick headache, jabs, and jolts) rarely create diagnostic confusion because of the short duration of the painful attacks and the highly distinctive characteristics of each of these syndromes.

Several historical factors can be considered “comfort signs” for primary headache. These include onset in adolescence or early adulthood, a stable pattern of similar headaches over a period of more than 6 months, positive family history, repeated association with menstruation, and variable location of headache from attack to attack or within the same attack. Several “red flags” are generally accepted as helpful to increase the index for suspicion of secondary headache disorders (Table 6-1).

Duration of the Headache Disorder and Age of Onset

Once it is established that the patient has a primary headache, it is useful to define how long it has lasted and how it has changed in severity and frequency over the years. Patients often seek consultation because of a worsening over the past 1 to 2 years. It then becomes particularly important to analyze possible mechanisms of this worsening, such as divorce, separation, loss of close relatives, or stress in the workplace. The age of onset is sometimes helpful. Primary headache disorders, particularly migraine, often begin in childhood, adolescence, or during the second or third decade of life. Cluster headache has an average age of onset at 28 years; tension-type headache can begin at any age. Headaches that begin after the age of 50 years more frequently are secondary, although some benign headache disorders, such as hypnic headache, occur most often in the elderly population (5).

TABLE 6-1 Historical and Examination Red Flags | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree